The gun believed to have been used to kill Emmett Till is now in the hands of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

A news conference will take place at 10 a.m. Thursday, the 70th anniversary of Till’s murder, at the Two Mississippi Museums to announce the donation of the .45-caliber pistol that J.W. Milam is believed to have used to pistol-whip and shoot the Black Chicago youth, who had just turned 14.

It’s the second murder weapon in the department’s possession. The first is the .30-06 rifle used in 1963 to kill Mississippi NAACP leader Medgar Evers, which can be seen at the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.

Unlike many stories plucked from history, fascination with the Till case has grown over time, said Dave Tell, author of “Remembering Emmett Till.”

He called the Till story “the ‘Ur-Story’ of American racism,” alluding to author Joseph Campbell’s reference to the archetypal plot in all major stories.

A year after Tell and other scholars launched the Emmett Till Memory Project in 2019, George Floyd died at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. Overnight, downloads quadrupled.

“In a moment when our country is on edge regarding race, the Till story is the story we keep going back to,” Tell said. “He’s the lens through which we understand race and what it means to be Black in America.”

In World War II, Milam served as a lieutenant in the Army Air Force and brought back the Ithaca Model M1911-A1 .45-caliber pistol, which has the serial number 2102279.

In Look magazine, Milam was quoted as saying, “Best weapon the Army’s got, either for shootin’ or sluggin’.”

A witness to Milam’s shooting prowess told the FBI, “I can tell ya how good he was with that old pistol. I seen him shoot bumble bees out of the air with it.”

Milam and his half-brother, Roy Bryant, abducted Till from his home in the wee hours of Aug. 28, 1955. The white men had heard that Till reportedly wolf-whistled at Bryant’s wife, Carolyn.

They took Till to a barn, where he was brutally beaten by Roy Bryant, Milam and others. Witnesses heard Till’s screams.

Till was beaten so badly there was talk of dropping him off at a hospital, but Milam reportedly killed him with a single bullet.

During the FBI’s 2005 investigation of the Till murder, authorities exhumed his body. X-rays revealed extensive skull fractures and metallic fragments in the skull. There were also fractures to the left femur and the left and right wrist bones. The Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office in Illinois concluded that Till died of a gunshot wound to the head.

During the autopsy, doctors found four lead fragments that experts determined were consistent with lead shot pellets. The size of those pellets matched the size of the lead shot manufactured for the Army Air Force.

An all-white jury acquitted Milam and Bryant of Till’s murder. Months later, they admitted their involvement to Look magazine.

The owner of the alleged murder weapon kept it in a safety deposit box in a Greenwood bank, according to Wright Thompson’s book, “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi.”

While working on his 2005 documentary, “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till,” filmmaker Keith Beauchamp discovered the existence of the .45 pistol. “I received the email of where the gun could possibly be,” he said.

He shared the email with FBI agent Dale Killinger, who investigated the Till case.

“Keith got a lead and let me know who to go see, and I rolled out, and I was able to connect with the people who got it,” said Killinger, who wouldn’t divulge how the gun came into their possession.

Killinger said he turned in the gun, which was examined for fingerprints.

He wouldn’t discuss who the owner is or what motivated that owner to donate the gun.

Beauchamp said he does have concerns about the gun being displayed in the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum. He doesn’t think Till’s mother, Mamie Till Mobley, would have approved, he said, “but I don’t hold the keys of history to Emmett.”

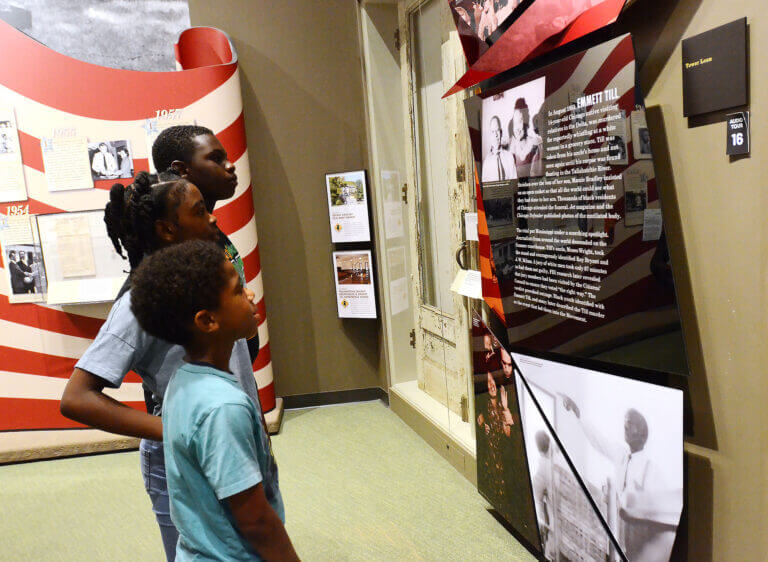

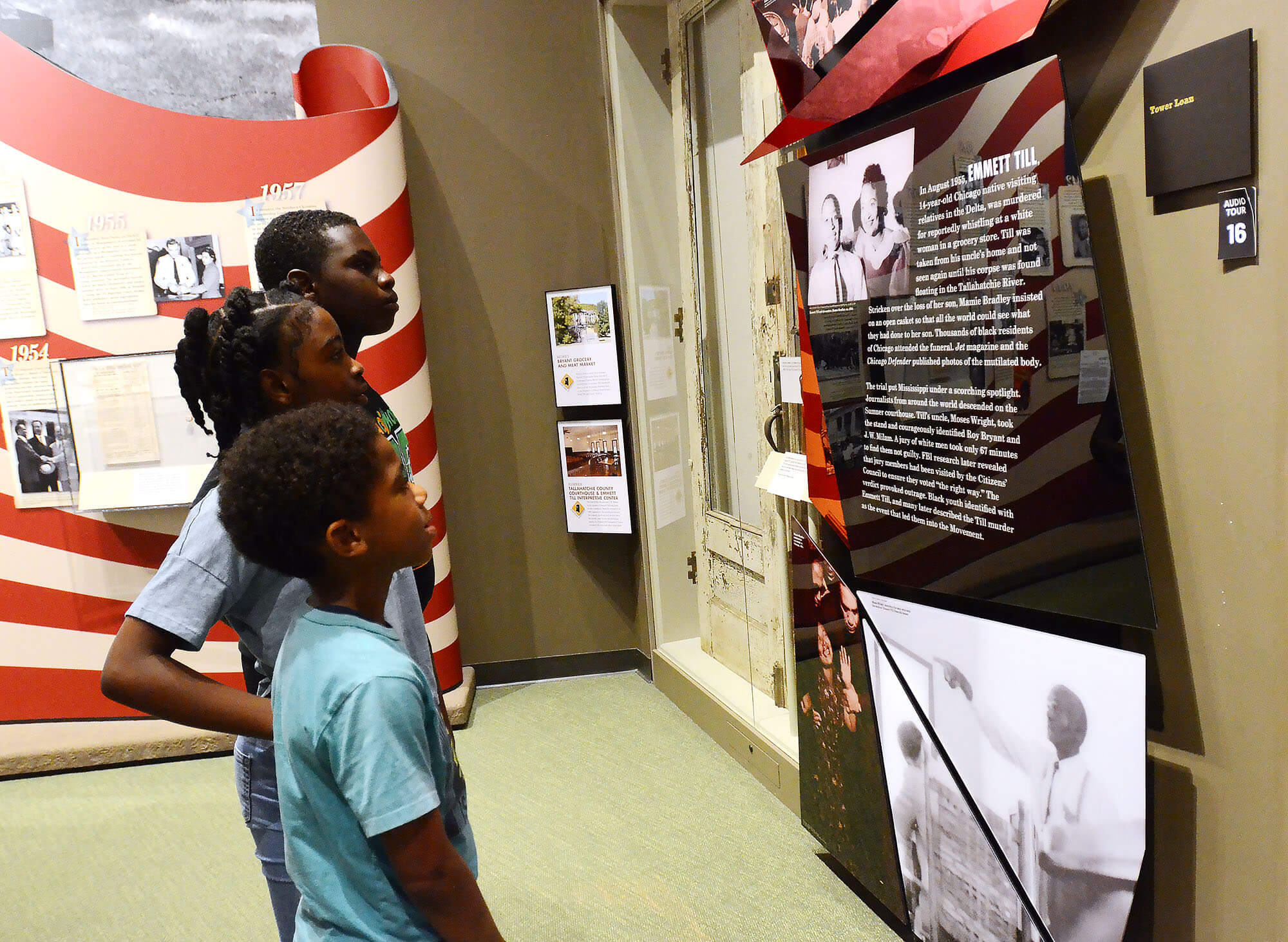

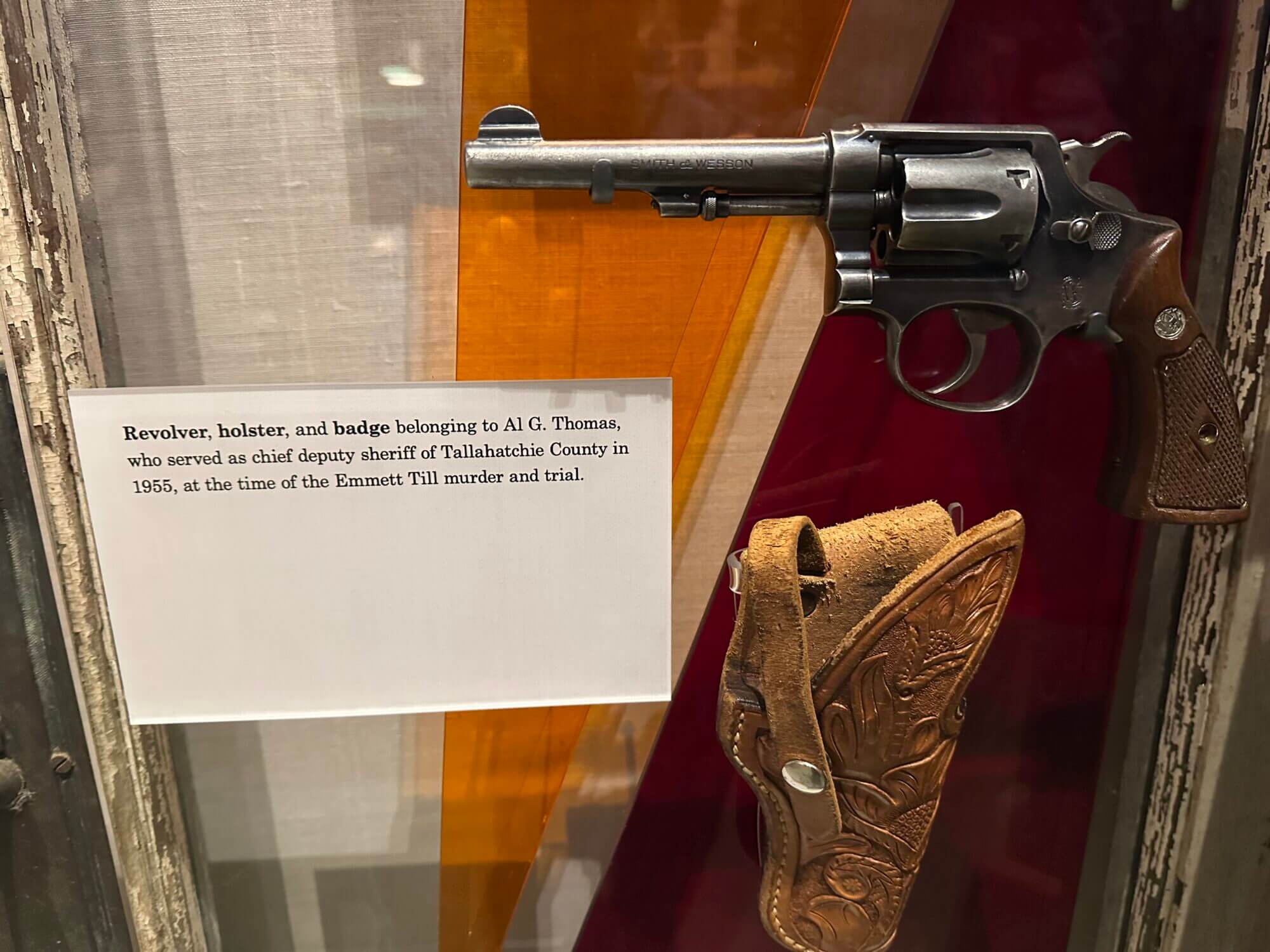

The Emmett Till exhibit in the museum does have a pistol on display. That pistol belonged to a deputy at the trial.

The archives department’s announcement comes days after the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board’s release of more than 6,000 FBI files regarding the Till case. Most are from 1955, when then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover said the agency lacked jurisdiction to pursue the case.

READ ALSO: Emmett Till lynching documents detail federal government’s response

Till’s cousin, Priscilla Williams Till, said she is anxious for the rest of the more than 30,000 pages to become public. “There’s a lot of unfinished documentation left out,” she said.

Devery Anderson, author of “Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement,” said he would like to see the release of all the documentation related to the FBI’s investigations on the case.

Beauchamp, too, is anxious to see all of the files released, he said. “That way people can see how the federal government, including the local authorities, dropped the ball in 2007 and 2017.”

In 2007, a Mississippi grand jury declined to indict Bryant’s then-wife, Carolyn, who testified that Till had mauled her in the grocery store. Weeks earlier, she had told a defense lawyer that all Till did was ask for a date and whistle.

The FBI made the case active again after author Tim Tyson claimed in his 2017 book, “The Blood of Emmett Till,” that Carolyn Bryant Donham admitted to him that she lied when she said Till all but raped her, grabbing her around the waist and propositioning her.

In its renewed investigation, the FBI found no such reference in recordings of his conversations with her, in transcripts of those recordings, or in Bryant Donham’s memoir, which maintains she told the truth when she testified.

READ ALSO: The Emmett Till lynching has seen more than its share of liars. Is Tim Tyson one of them?

The lack of independent corroboration, the FBI found, “would prevent the government from proving, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Bryant-Donham recanted her testimony when she spoke with Tyson over a decade ago and, consequently, that she lied to FBI agents when she denied having done so.”

The 2021 report concluded that no one could be prosecuted.

Donham died in 2023.

- Former Hinds sheriff Marshand Crisler’s bribery conviction stands - March 4, 2026

- National Rifle Association successfully lobbies against bill taking away guns from abusers - March 4, 2026

- Data center proposed for Clinton - March 4, 2026