Anna Wolfe

Jackson Public Schools students are conducting all of their classes this semester online. But that doesn’t mean they’re all at home. The Boys and Girls Club has opened its doors for working parents who cannot leave their children at home alone. At the Club’s Walker unit in south Jackson, organizers turned the gym into a makeshift classroom, with plastic tables spread out over the basketball court and cardboard partitions separating each student, as seen here on Sept. 14, 2020.

Are the kids alright?

During COVID-19, kids in Mississippi’s capital city are overcoming mammoth challenges unique from any generation before them — and doing it with grace.

Where the pandemic has illuminated historic unmet needs, it’s also put the community’s strength on display.

BY ANNA WOLFE | SEPT. 30, 2020

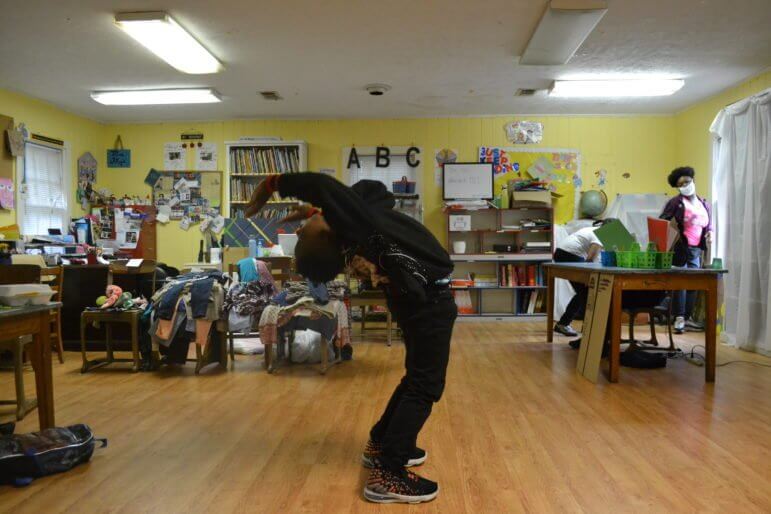

Kharter, a second grader at Galloway Elementary School in west Jackson, wiggles out of his seat at the Stewpot After-school Program where he’s completing a virtual grammar lesson and strikes a ninja pose.

He nails the look with the black facemask he’s wearing, not as part of a costume, but to guard against the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Anna Wolfe

Khamiya, 7, a second grader at Galloway Elementary School in west Jackson, dances outside of Stewpot’s after-school center, which started operating during the day to care for kids while they conduct their distance learning as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, on Sept. 24, 2020. Khamiya said she would rather attend school in person, but she said she recognizes virtual is a safer option.

His classmate Khamiya finishes her schoolwork before begging the teacher to go outside, where she’ll dance on the porch on a gray, drizzly day in late September. She hopes her dad will take her shopping at “Toys R Us” later.

Down the street, Javier and Kelvi, a second and third grader, dart through a classroom at the Boys and Girls Club Capitol Street unit, snatching stacks of notebook paper strips — handmade play money — off each other’s desks. Kelvi soon loses interest in hoarding her stash and playfully tosses the fake cash, letting it shower the linoleum. Her classmates dive to scoop it up.

The last six months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the deaths, layoffs, evictions and school closures, have brought immeasurable hardship and heartache, especially to Black and poor communities in Mississippi. The rippling effects seem to have altered most aspects of everyday life — except for a child’s nature.

“They’re still learning with virtual learning. They’re able to still play,” said Brooke Floyd, director of children’s services for Stewpot Community Services. “Like, I think that’s a beautiful thing, when you put kids out in the yard and they don’t have any toys or can’t use the equipment and they still have fun and you can hear the laughter.”

“To me, that’s letting us know that everything’s going to be okay.”

With more than four in ten already living in poverty, Jackson children have long felt the unmet needs — perhaps most visibly a historically underfunded and segregated school system — that the pandemic has illuminated in their communities.

Anna Wolfe

Kharter, a second grade student who attends Stewpot Community Services’ youth program, takes a break from schoolwork on his computer to show off some moves on Sept. 24, 2020. He said he’s the Nine Tailed Fox from Naruto, a Japanese comic series. Later, he works with his teacher Mrs. Brooke on mastering adverbs. Virtual learning has made continuing education for Jackson Public Schools students during the COVID-19 pandemic possible.

Nearly every child in Jackson Public Schools is Black and lives in a low-income household, qualifying them for free or reduced lunch. School buildings never opened back up after March, spurring a frustrating fight to obtain enough E-learning technology for every student and sticking most families with tough decisions about where their kids will spend their days.

Unemployment benefits are dwindling and despite a federal moratorium, evictions have continued. And while efforts to get meals to children have been possibly the most valiant, food scarcity and affordability remains a persistent problem across the capital city.

This school year so far, the district has recorded 2,600 children — a tenth of their student body — as homeless, which usually means they are living unstably at other families’ homes. Still, about a third live in shelters or hotels. But this isn’t a COVID-19 problem: Last year, JPS had 3,100 enrollees in the federal McKinney-Vento grant to serve homeless students.

“A lot of our kids are so accustomed to going through a lot that it kind of rolls off them,” said Penney Ainsworth, CEO of the Boys and Girls Club of Central Mississippi. “Kids will adapt to whatever the setting is and what’s going on. But it’s a scary time. So they’re nervous, but they’re resilient.”

Playtime after a long day of virtual learning

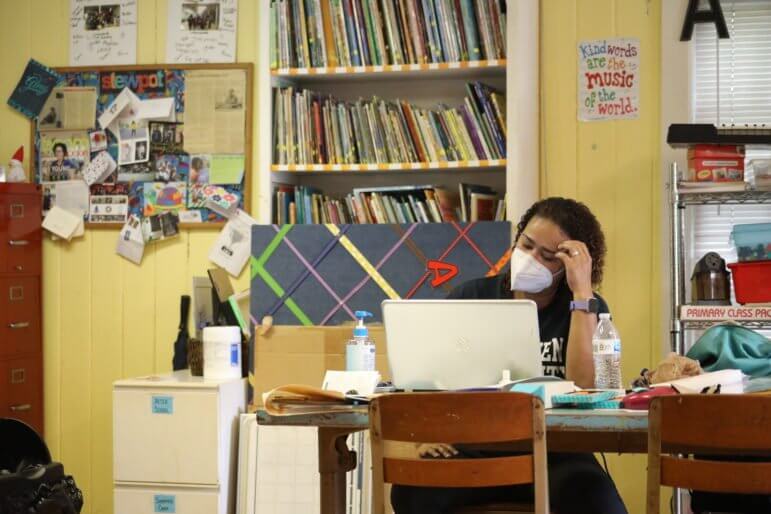

Jackson Public Schools does not gather data showing where kids are conducting their virtual schoolwork, the district spokesperson told Mississippi Today, but many traditional afterschool programs like Stewpot Community Services and the Boys and Girls Club started operating at a lower capacity in the daytime to accommodate working parents.

Floyd normally has 40 students at her center, a bright blue house close to the city’s primary soup kitchen. The day camp is limited to 20 kids to ensure they can adhere to social distancing. These community organizations are, too, not able to offer the consistency and stability of the public schools. Just Monday Stewpot had to cancel virtual school for the day after a break-in occurred over the weekend.

“For people to expect the worst or think that the worst is going to happen, I’m not buying it. Even parents that are poor want their kids to succeed and they’re going to try their best to make it happen.”

—Brooke Floyd, director of children services for Stewpot Community Services

Some parents have jobs working from home, a separate, difficult juggle, but many are relying on grandparents, aunts, cousins, friends and neighbors to fill in the child care gaps.

Other families are simply uncomfortable with the idea of placing their children in a center during a pandemic, Floyd said, especially knowing the virus has disproportionately taken the lives of Black people. So they’ve done whatever they must, even altering their work life, to keep their kids home.

Floyd and Ainsworth said they have contact with many of the families they’re not serving during this time. They know they can call if they’re in need, Floyd said, “and they do.”

But child services coordinators also recognize there are some children falling through the cracks. Floyd recalled meeting kids over the summer that she’d never seen before while delivering bags of food to apartment complexes where her students live.

“Kids ran to the van. They were like, ‘Can we have a bag?’ And I was like, ‘Where’s your mama?’ ‘I don’t know,’” Floyd said through tears. “I was like, ‘Oh my god. Who are you? What’s your name?’

“They’re lost,” she said. “We help the kids right in front of us, but if you work with children, you’re like, ‘What’s happening to the other kids? Who’s helping them? Who’s checking up on them?’”

Onlookers are quick to blame parents, she added, but a longstanding lack of access to affordable childcare and the drop in unemployment benefits in August have put some working parents, especially those without family support, in impossible situations.

“If I am doing everything I can for my children to survive, unfortunately sometimes I’m going to have to leave them,” she said.

Anna Wolfe

Left/top: Some of Jackson Public Schools’ fourth, fifth and sixth graders conduct their virtual learning from a classroom inside the Boys and Girls Club Capitol Street unit on Sept. 21, 2020. Right/bottom: Johnathan Thomas, a construction estimator for the Mississippi Department of Transportation, a Club volunteer and dad, oversees the class. When he first offered to facilitate, he thought he could use the time to complete his work, but a student in his class lacked a laptop and was conducting her lessons paper packets, so he’s letting her use his computer. He’ll work in the evenings to make up for it.

“I think JPS kids are well-adapted … The ones that go here, I think they’re pretty much well-rounded, well-disciplined kids … Everyone’s respectful and that’s all I can really ask for,” Thomas said.

Jackson Public Schools is still offering breakfast and lunch to students during the closures, which has been a big help for the private centers. But the district isn’t otherwise subsidizing these programs, Ainsworth said, leaving most of the physical responsibilities that usually fall on public schools — staffing, sanitizing and keeping the lights on — to a patchwork of community partners.

“School is a safe place for many of our students and not being able to be in that safe place and be around friends and share experiences and that whole social aspect of schooling has all of our hearts heavy,” said Bobby Brown, principal at Jim Hill High School in west Jackson.

Jackson’s youngest virtual learners

Even students who secured devices to use for distance learning have had trouble accessing their classes.

“We kinda have trouble getting into WiFi and stuff because it kinda shut down sometimes and we have to wait for a few minutes,” Keiyana, a fifth grader at Casey Elementary School, told Mississippi Today. “One time I missed class because of that.”

Khamiya, the 7-year-old, said doing all her schoolwork on the computer makes her tired and her hands ache.

“I don’t like online. I want to learn in the classroom. I like it (in-person) but I don’t want to get corona,” Khamiya said. “Whoever made it (the virus), I don’t know who made it, but they should have never made it.”

Kieyana, who attends the Boys and Girls Club Sykes unit in south Jackson, said virtual class is different in one way that adults might not expect: She said her teachers are less likely to yell at students over video calls “because they know that you’ll tell.” Keiyana is a good student; she said she’s getting all A’s and especially likes math and science.

When she grows up, she wants to be a pediatrician, a perfect mix of her favorite school subjects and her love of helping care for babies. She said she wishes her school had a gym like the one she plays in at the Club and that her teachers “would stop yelling every now and then.”

Top childhood development experts aren’t as worried about what the impact of COVID-19 and distance learning will be on a child’s ability to keep up with school curriculum. Susan Buttross, a professor of child development at University of Mississippi Medical Center heading up the Mississippi Thrive! Child Health Development Project, said she’s more concerned with the loss of social connections and positive adult reinforcement.

“It’s not that we think kids can’t learn in distance learning,” Buttross said. “People are struggling with making enough money to survive. They’re struggling with so many other social determinants of health, being able to access the right kind of food, and jobs and housing and all of that. So many times, the primary caregiver at home is not equipped to then be the teacher too.”

Anxiety surrounding the virus and grief over a death in the family only compounds the chronic stress children living in poverty already endure. Fleeting stress is normal, Buttross explained, but toxic stress, when a child is constantly on high alert and their stress response system becomes overwhelmed, can hinder their brain development and wreak havoc on their health.

Research shows that the toxic stress of poverty — resulting from economic hardships, racial discrimination, deaths of loved ones or living in an area where violence is prevalent, for example — affects the part of the brain used for decision-making.

Khamiya said her family recently chose to move into a new apartment complex in west Jackson that they thought was in a safer neighborhood.

“We’ve been talking about community. It’s the area where people work and play,” Khamiya said, then she answered how she felt about her west Jackson community: “It’s good, but I don’t like how be people be shooting and killing people.”

The location of prominent community service agencies, west Jackson also has a higher concentration of homeless people than other parts of the city, and therefore higher visibility to someone like Khamiya.

“Do you ever feel bad for homeless people?” she asked this reporter. “I got feeling sad because they need money. They need a house. They need to feel safe.”

Anna Wolfe

Khamiya, a second grader who attends Stewpot Community Services’ youth program, gets some fresh air after finishing her virtual lessons for the day on Sept. 24, 2020. When she grows up, Kamiyah said she wants to perform dance and that one of her biggest goals is to own her own car.

Not only are Black Mississippians disproportionately impacted by the nation’s wealth imbalance — three times more likely to live in poverty than whites — they’re also grieving at a higher rate due to converging national crises.

Almost one-third of Black Americans said in a Washington Post-Ipsos survey that they personally knew someone who had died from COVID-19 — compared to less than 10 percent of whites — which coupled with a national spotlight on policy brutality has spawned a bereavement crisis in Black America, Marissa Evans writes in a recent The Atlantic article.

A pair of siblings in Floyd’s program lost their mom in June. Floyd said she was in her thirties and died in her sleep. She didn’t think the mother had been sick.

Another former student, not even 20-years-old, took his own life this summer after becoming entangled in the criminal justice system.

Right as the pandemic began, Stewpot’s bus driver died from cancer. The kids were heartbroken. And they couldn’t have a memorial service due to social distancing.

Anna Wolfe

Elementary school kids conducting their virtual learning from the Boys and Girls Club Capitol Street unit play with fake money they crafted out of strips of notebook paper. Kelvi, center, said she wants to be a cook when she grows up, but quickly clarifies that she doesn’t want to pay bills. “It’s too hard,” she said.

“People can’t properly grieve right now,” Floyd said. “It’s almost like, you have to just keep moving the same way you were before because if you sit still and think about it, you’re going to lose it.”

But researchers working on toxic stress have also identified the ways to bolster resiliency for kids facing adversity.

“The one factor that keeps coming out is having one adult in their life who is positive, a ray of sunshine for them,” Buttross said. “One person who encourages them and helps them along … Somebody out there who says, ‘You’re good. You’re smart. You’re awesome. You can do something.’”

“It might not be a parent,” she added. “It might be a grandparent or a teacher.”

Or a volunteer at the after-school program.

Ainsworth, the local Boys and Girls Club CEO, said she herself grew up in government housing with a single mom and eight siblings in Norfolk, Virginia.

“My four blocks of the world did not define who I was and who I was going to be. That’s my desire for my Boys and Girls Club babies,” Ainsworth said. “I need them to know that this situation that you’re in right now, it may be bleak. But if we look to your future, we keep exposing you (to opportunity) … through workforce development, college tours, and those things, the sky is the limit for you too.”

At work and play

Simultaneously, the pandemic has also produced a flood of resources and people called to help.

“Hopefully those people that are in need realize that there is almost an influx of support right now,” Floyd said.

This extends beyond the help that has come with federal pandemic relief packages, such as large investments in internet connectivity and devices for school children, increased food and unemployment benefits and extra money for housing assistance.

Jackson Public Schools received a nearly 70% increase in its annual McKinney-Vento grant to serve homeless students, some of whom also receive services at Stewpot. Faith Strong, the district’s coordinator for homeless services, said she hopes to hire more social workers who can work more directly to address individual students’ needs.

The Mississippi Food Network partnered with the district to distribute family food boxes with enough fresh and frozen foods to last a family several days. The Boys and Girls Club, the City of Jackson and Meals on Wheels partnered initially and delivered roughly 20,000 meals across the city.

“There were just churches with lines out in front of them handing out boxes to whoever showed up,” Floyd said. “I’ve been proud to watch as it’s happened.”

Even before the pandemic hit, Dole Packaged Foods, a subsidiary one of the world’s largest fruit and vegetable producers headquartered in California, chose Jackson as the first city it would bring its Sunshine for All program aimed at fighting food insecurity. The company called Mississippi’s capital city one of the largest food deserts in the nation. Dole partnered with the Boys and Girls Club and has been hosting a farmer’s market at the Capitol Street unit, where people can purchase fresh produce from local Footprint Farms.

Anna Wolfe

Lakeise Yarn and her mom Ebony volunteer at Dole Packaged Food’s Saturday farmer’s market at the Boys and Girls Club Capitol Street unit. On Sept. 12, 2020, the local partners served free hotdogs and smoothies to passersby in west Jackson. Lakeise has also participated in Dole’s cooking camp and said she’s enjoyed getting to explore new foods.

“Me and my daughter have really benefitted from being able to come and give back on a Saturday, as well as the meals. It has been a big help to me, cause I’m a single parent,” said Ebony Yarn, a Club employee and volunteer. “I fall in the gap where I make too much to get assistance but then I don’t make enough, per se, to handle everything I need to do.”

Dole is also supporting local food hub Up in Farms’ Farm-to-Table Training Center and providing 1,000 meals to the needy; launching a virtual cooking camp that teaches kids about nutrition and cooking; and building community gardens at Boys and Girls Club locations.

“It’s truly unfair that the kids here in Jackson are limited in fresh fruits and vegetables or opportunities to go into a store and get it and it just came from the vine,” Ainsworth said, “but yet if they go down the street to Madison County, the food is being washed as it’s set down, you know? It’s fresh.”

The poverty rate in Jackson is about eight times higher than the 3.3% poverty rate in the city of Madison. For Ainsworth, these food programs are about more than nutrition.

“What I want to do is make sure that we are exposing our kids to knowing that you are worthy of any and everything that you desire,” she said.

The post Are the kids alright? How Jackson students are surviving the pandemic. appeared first on Mississippi Today.