Editor’s note: This essay is part of Mississippi Today Ideas, a platform for thoughtful Mississippians to share fact-based ideas about our state’s past, present and future. You can read more about the section here.

My parents were born in 1945 Tylertown in southwest Mississippi. Despite being raised in rural homes where overt racism was served up as often as turnip greens or buttermilk biscuits, Dad and Mom refused to pass down to their children the generations-old heirlooms of animus and fear. No racist jokes. No slurs. No stray remarks about knowing one’s place and no lamentations about lost traditions or unwelcome changes. And whom do I have to thank for this gift that changed the trajectory of my life? Uncle Sam and the United States Air Force.

As it did for so many young men from small farms in far-flung rural counties, the military and ROTC provided Dad with a pathway to college and a career after graduation.

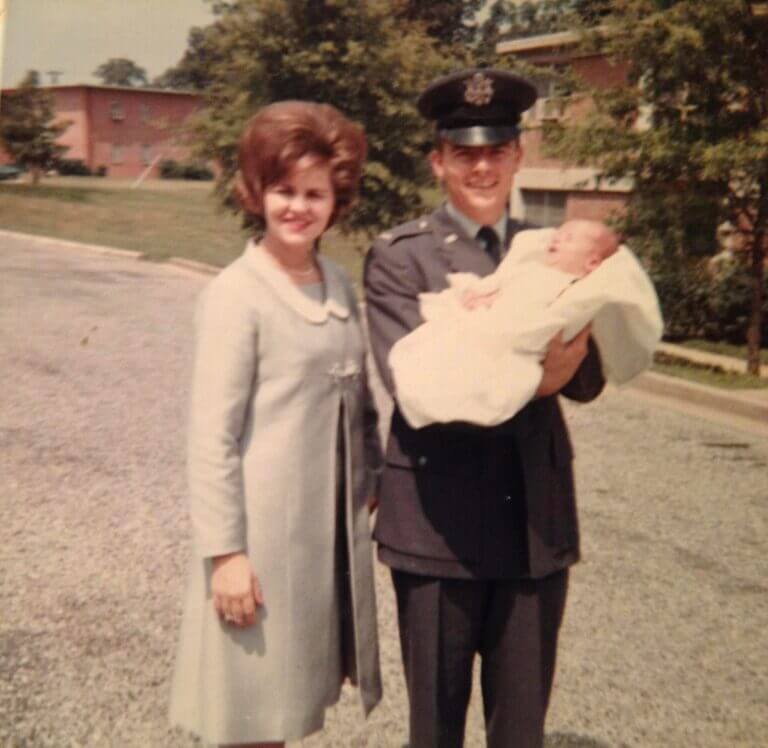

Upon graduating from Ole Miss in 1967 with an obligation of active-duty military service (and a two-week-old baby, me), the Air Force sent my father to Texas A&M to obtain a master’s degree in computer science and start down the road toward becoming a military officer. When he left College Station, the next stop was officer training school.

An important thing happened during that period between completing his formal education and being sent off to Vietnam. The Air Force confronted Dad with the hard truth about racism in our country and our military – and they made it crystal clear that it would not be tolerated from Air Force officers.

More times than I can count, Dad has told me the story of a crusty officer barking out, “In the United States Air Force, there is no white, there is no black, there is only Air Force blue!” That same officer told Dad and other young officers from the South that their particular brand of prejudice might be quickly cured by a glimpse at the scores from IQ tests administered to all in attendance.

And as Dad moved through the mandatory “race relations” component of his training, another important thing happened. He got to know the Black officers from his squadron. He ate meals with them. He learned to play handball with them. He figured out that they wanted the same things he did.

As Dad puts it, “They just wanted to marry a pretty girl, get promoted, drink a cold beer once in a while, and maybe take a decent vacation.”

Dad didn’t like everything they said to him in that class, and he admits that he sometimes got angry. But on the handful of occasions when I have discussed with him how it came to be that he and Mom ended the cycle of overt racism in our family, he consistently has credited the fact that the Air Force told him hard truths about who he was and afforded him the opportunity to discover the painful reality that what he was told around the dinner table in Tylertown was a source of pain and oppression for those new friends about whom he cared deeply – and with whom he shared table as an adult soldier.

The training Dad experienced was part of a national effort in the late 1960s and early 70s to address racial division and inequality in our military. On March 5, 1971, the secretary of Defense announced that the effort would be expanded to require every member of the armed forces to attend classes in race relations.

As part of that historic effort, the Defense Race Relations Institute trained 1,400 race relations instructors in a single year. According to the New York Times, a bibliography of “100 of the most important works on the Black man in America” was contributed to the Institute in hopes of educating soldiers on the challenges confronting our country.

As a direct beneficiary of that historic effort, I am deeply disturbed by the fact that the difficult and important lessons the United States Air Force taught my father would be illegal today, 55 years later, if presented in any Mississippi school or university.

Mississippi’s new anti-DEI law prohibits requiring “diversity training” in our schools and universities and defines that term as “any formal or informal education, seminars, workshops or institutional program that focus on increasing awareness or understanding of issues related to race, sex, color, gender identity, sexual orientation or national origin.” (Emphasis added by me).

In a world where we still are plagued by bias and racism, and at a time when we remain deeply and violently divided, Mississippi politicians have outlawed efforts to increase awareness and understanding of issues that are as complicated today as they were when I was a young boy. They have made illegal conversations and lessons that our armed forces – not Harvard University or the University of Virginia – deemed central to the security, morale and identity of our nation.

Sticking our heads in the sand, or elsewhere, and “protecting” our children from our painful and violent past does them, and Mississippi, no good. It shortchanges and underestimates young people who are fully capable of talking about hard things, fosters the stereotype of Mississippi as a place where ignorance and injustice flourish, and is a slap in the face of all those like Dad who did the hard work of grappling with the truth and fighting for our freedom to tell it.

Cliff Johnson is a civil rights lawyer and law professor in Oxford, Mississippi. Johnson is a graduate of Mississippi College and Columbia University School of Law, and he speaks frequently on the intersection of law, politics and religion.

- State Supreme Court considers reviving former Gov. Phil Bryant’s lawsuit against Mississippi Today over welfare scandal coverage - February 18, 2026

- Winter storm update: Mississippi still waiting on fed declaration for individual assistance, lawmakers crafting plan to fund recovery - February 18, 2026

- Shy of special session, Mississippi school choice appears dead - February 18, 2026