The notion that Elvis derived much of his musical, performative and sartorial style from African Americans is hardly new, and neither are the debates about whether this involved inspiration, borrowing or appropriation.

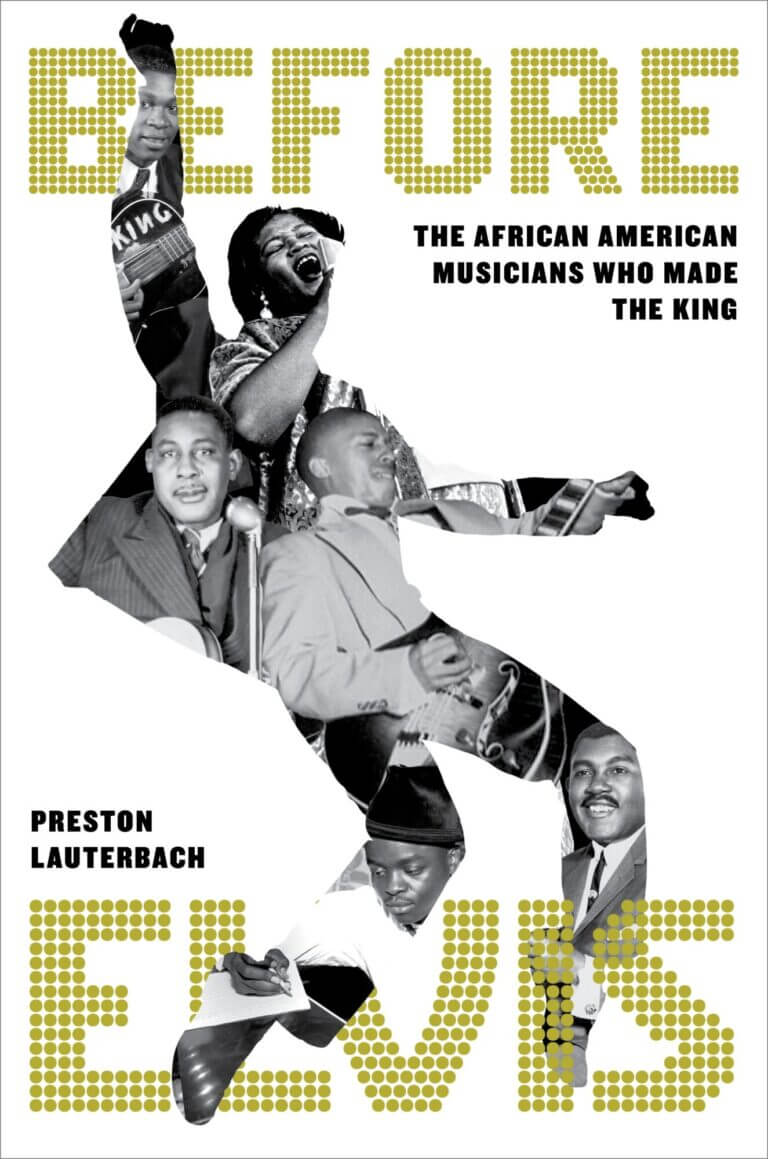

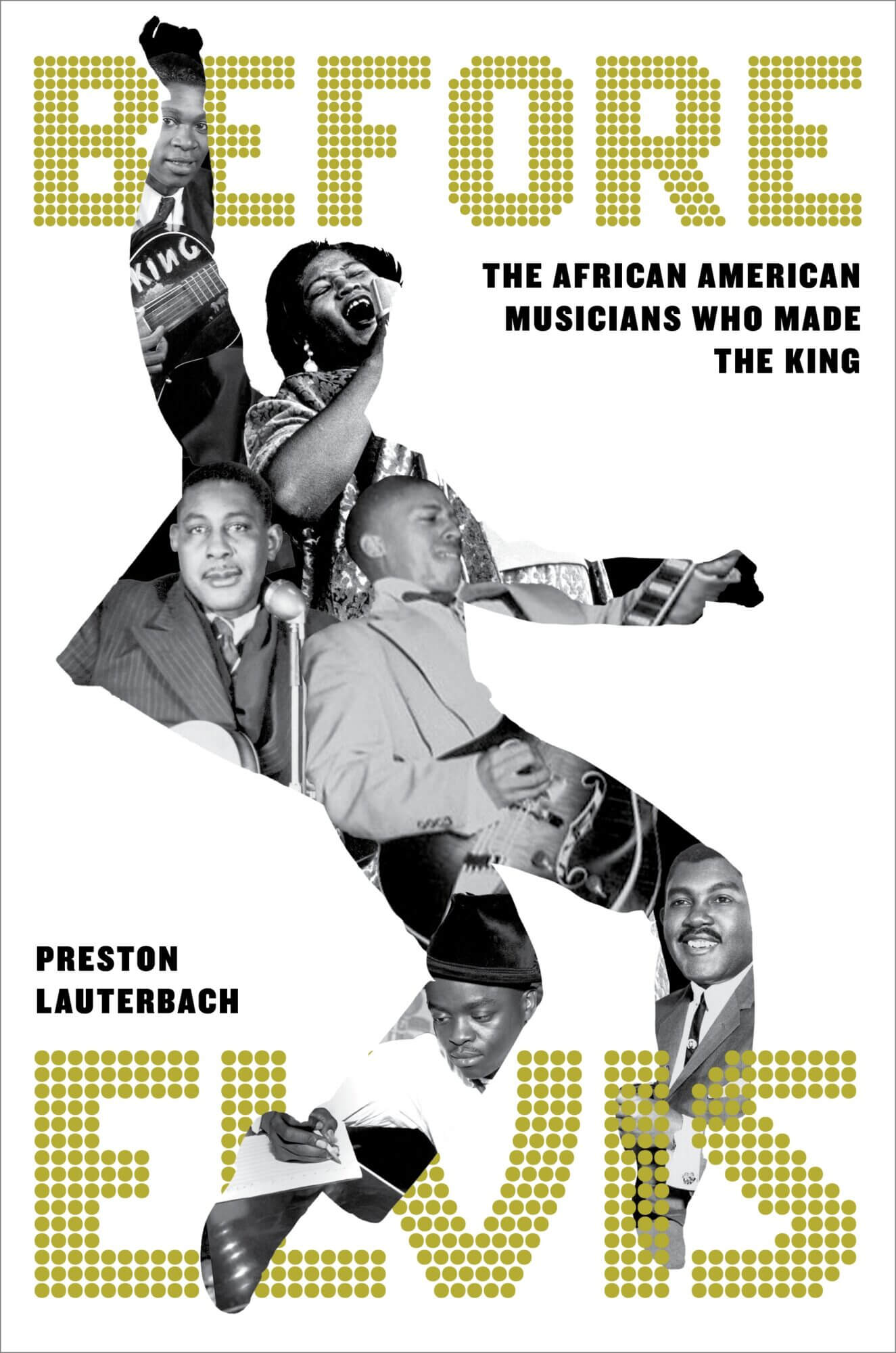

Issued on the 90th anniversary of Elvis’s birth on Jan. 8, Preston Lauterbach’s “Before Elvis: The African Americans Who Made the King” engages with these contentious issues though his central argument is that in the voluminous literature on the King the influences from African-American culture have simply not received their “due attention.”

“In debating good and evil,” Lauterbach writes, “we can lose sight of what happened in real time.”

Lauterbach came well prepared for the task, having written three books on African-American life and culture in Memphis [“Beale Street Dynasty,” “Bluff City” and “Timekeeper”] and the groundbreaking “The Chitlin’ Circuit: The Road to Rock’n’Roll.” The latter addresses how a national network emerged in the ‘30s and ‘40s connecting regional African American entertainment districts, including Beale Street, facilitating greater professional opportunities for Black artists.

Thirteen-year-old Elvis and his family left Tupelo for Memphis in late 1948, a time when the music industry was undergoing other radical changes that contributed to a vibrant rhythm and blues scene and, ultimately, the emergence of rock’n’roll.

In 1947 Memphis’ WDIA became the first station in the country to feature all African American programming and on-air staff, including deejays B.B. King and Rufus Thomas. And it’s likely that Elvis first heard the blues in Tupelo via Nashville’s 50,000-watt powerhouse WLAC, where white deejay Gene Nobles started a rhythm and blues show aimed at Black listeners in 1946.

The growth of Black radio programming was spurred by changes in FCC regulations that doubled the number of stations, which turned them away from national networks to concentrate on niche audiences, notably blues and country. This in turn aided upstart independent record labels that were capturing the new sounds being created in cities across the country. Memphis’ Sam Phillips, who discovered Elvis, started his career by producing recordings of local artists, such as Howlin’ Wolf, that he sold to L.A.’s Modern and Chicago’s Chess labels before founding Sun Records in 1952.

Did Elvis steal music from Black artists?

Rather than inventorying the many artists who influenced Elvis, Lauterbach focuses instead on a select group, including two Mississippians. Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup from Forest was the source of Elvis’s initial Sun single “That’s All Right,” issued in July 1954, while Clarksdale native Herman “Junior” Parker recorded “Mystery Train” for Sun two years before Elvis’s cover version for the label.

He also devotes considerable space to Willie Mae “Big Mama“ Thornton, an Alabama native who had a 1953 hit with “Hound Dog” on Houston’s Duke Records. Elvis’s considerably less raucous take was a smash on RCA Victor in 1956, reaching No. 1 on the pop, country and rhythm and blues charts. Thornton famously claimed that she only ever earned $500 off of the record. But did Elvis steal from her?

This is an oft-repeated charge, but an answer requires looking into the way that money flows in the recording industry, where most money stems from copyright rather than recorded performances. “Hound Dog” was written by two young white songwriters, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who sold the publishing for $1,200 to Duke’s owner, Don Robey, an African American Houstonian. The $500 Thornton earned was likely an advance on royalties.

Robey claimed the record sold 500,000 copies, very likely a lowball , and at the going royalty rate of .5 cents per copy those sales should have yielded Thornton at least $2,500. Any earnings from Elvis’s successful single and the song’s subsequent appearances on albums would have gone to Robey. It’s notable that considerable royalties for the flip side of the record, “Don’t Be Cruel,” went to African-American songwriter Otis Blackwell, who wrote multiple songs recorded by Elvis including “All Shook Up” and “Return to Sender.”

The case of Crudup is equally sad. Between 1941 to 1954 Crudup recorded prolifically for RCA associated labels, and Elvis no doubt heard his records on the radio and jukeboxes. In 1956 Elvis told reporters “Down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now.”

Crudup was paid for his recording sessions, but yielded little or nothing in royalties for his compositions at the time or after Elvis covered his songs—in addition to “That’s All Right” Elvis recorded “My Baby Left Me” and “So Glad You’re Mine.” RCA was likely prompt in paying the royalties to the large publishing firm Hill & Range for Elvis’s versions, but it wasn’t until after his death in the early ‘70s that Crudup’s family began to receive what turned out to be millions.

What happened to Black artists ‘after Elvis’?

These stories are generally known, though Lauterbach provides considerably more detail on the artists’ lives and careers than in previous works. And despite the title of the book, he also devotes a third of the book addressing what happened to his subjects “after Elvis.”

Thornton drew upon her association with Elvis in trying to reestablish a career, but experienced bouts of poverty before becoming a popular act on the blues revival circuit in the late ‘60s. Crudup had retired from music by the time Elvis debuted, and likewise enjoyed some success on the ‘60s revival circuit, but made much of his meager living transporting migrant workers along the East Coast.

The book also spends considerable space addressing less known influences. The Presley family attended church just blocks from the East Trigg Missionary Baptist Church, whose leader, the Rev. W. Herbert Brewster was a pioneer in gospel songwriting. He used his pulpit and a popular WDIA radio show to denounce segregation, and in 1953 Brewster openly invited white visitors to East Trigg, and Elvis was a regular.

Elvis earned the nickname “the hillbilly cat” from his fresh mix of the sounds of country and the blues, and Lauterbach argues that an overlooked element in his appeal was Black gospel, which Presley acknowledged was his “first love” in music. At Sunday night gospel shows at East Trigg he learned powerful lessons in “working the house” from masters of bringing the audience to ecstasy.

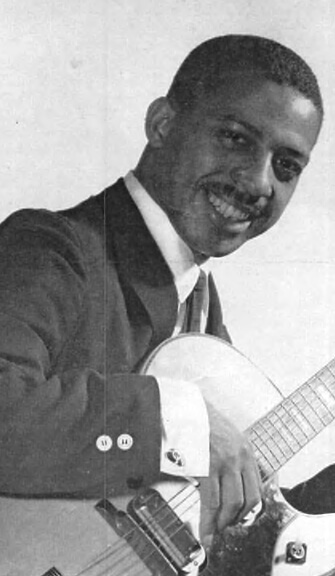

A key to understanding Elvis’ seemingly revolutionary arrival on the Memphis scene in the summer of 1954 was the African-American guitarist Calvin Newborn. His family band, led by drummer father Phineas Sr. and including brother Phineas Jr., later a jazz piano legend, was the hottest group in the area, playing largely for white audiences in the wide-open nightlife scene across the river in West Memphis.

They backed B.B. King on his first recordings in 1948 and toured with Jackie Brenston following the 1951 release of the Sam Phillips-recorded “Rocket 88,” often described as the first rock-‘n’roll record. Elvis befriended Calvin, who referred to the band’s musical approach as one of “boogiefication.” Elvis became a frequent witness to their power in May 1954, when white patrons were invited to attend Beale Street’s Flamingo Club, where the Newborns were the house band.

Elvis was enthralled with Calvin’s electric stage routine, perhaps adopting his leg-shaking, and was invited to participate with the band. Musician Honeymoon Garner recalled that a song that Elvis chose to perform was Roy Brown’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight,” which months later was featured on Elvis’ second single.

“Before Elvis” is stunning in how it intricately weaves stories about the five main characters in a manner that captures both the singularity of what Elvis accomplished and how he reflected burgeoning forces that revolutionized music-making.

The post Book explores the African Americans who made Elvis ‘the King’ appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- UMMC keeps clinics closed and cancels elective procedures Monday and Tuesday amid recovery from cyberattack - February 22, 2026

- With school choice, what about the students left behind? - February 22, 2026

- Scott Colom raised most money, but Cindy Hyde-Smith has most cash before March primary - February 21, 2026