Yellow buses pulled up to grassy curbs and carried students from the far reaches of Copiah County to school campuses in Crystal Springs and Wesson. For teachers, parents and students, the first day of the fall semester was an ordinary August day in central Mississippi. Hot, humid and long.

For administrators, it was the end of a probation that started over half of a century ago.

After 55 years, the Department of Justice lifted Copiah County School District’s desegregation order. The district had integrated to the agency’s satisfaction and can now forgo regular audits that check for inequity.

However, across the county, parents along a racial divide still see existing inequalities: better facilities and programs in mostly white Wesson and older buildings and few offerings in Crystal Springs, which is majority-Black.

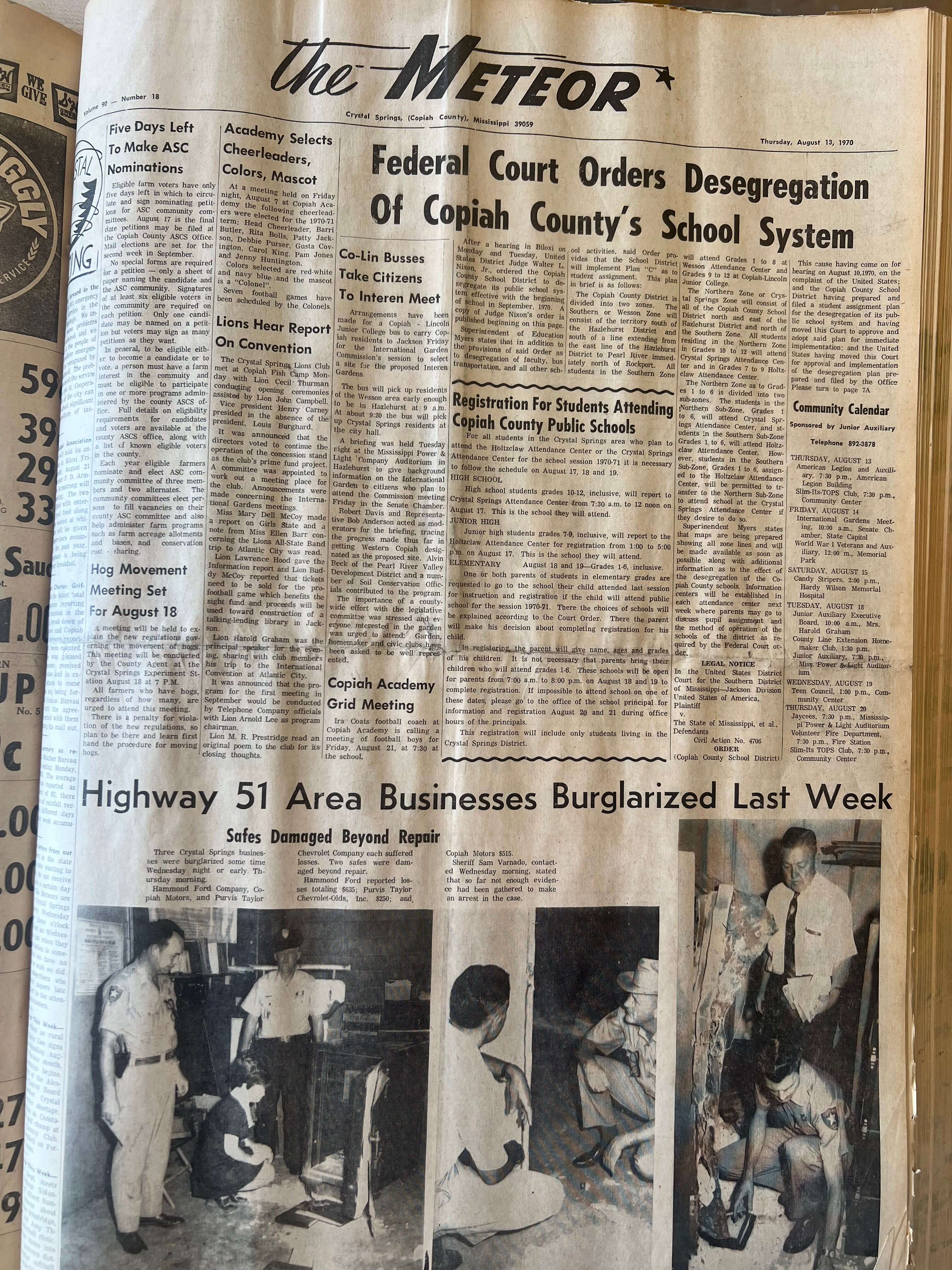

Sixteen years after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education declared segregated schools were unconstitutional, Mississippi was compelled by a subsequent court decision to dismantle its dual school system beginning in 1970. Some districts like Copiah County faced specific desegregation orders based on their level of compliance.

“The goal was to ensure that school districts were meeting their obligations,” said Shaheena Simons, who up until April worked for the Civil Rights Division in the Department of Justice. “That meant that the DOJ would ask questions and would review information and would sometimes go out on site and talk to people. The goal was to ensure that the school district was treating students fairly.”

In 1970, Copiah County School District joined over 200 others across the South under school desegregation orders: 33 in Mississippi, 53 in Alabama, 49 in Georgia, 44 in Louisiana, 28 in South Carolina, 27 in North Carolina and 35 in Virginia. Now, 29 districts remain under that order in Mississippi, 30 in Georgia, 12 in Louisiana, and 39 in Alabama. The other Southern states have fewer than five districts remaining.

More than 50 school districts were released from DOJ desegregation orders during Donald Trump’s first presidential term, more than during the two terms of Barack Obama, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush and the single term of George H.W. Bush. President Ronald Reagan released just under 150 school districts from orders, more than any other president.

In July, Copiah County School District Superintendent Rickey Clopton submitted paperwork through the board attorney after communication from the Department of Justice that the new administration intended to clear desegregation orders with a greater sense of urgency than past administrations. He didn’t expect to hear back so soon. The turnaround was a week.

“We’re just fortunate that someone in the Department of Justice has taken the initiative to try to settle some of these things and get us out of the past and move into the future,” Clopton told Mississippi Today.

The court order came down on the first day of school – and was news to longtime administrators and local activists. One central office employee found out from a press release, while an assistant superintendent got the news from a 20-second evening news clip. The local NAACP chapter president didn’t know until Mississippi Today informed him.

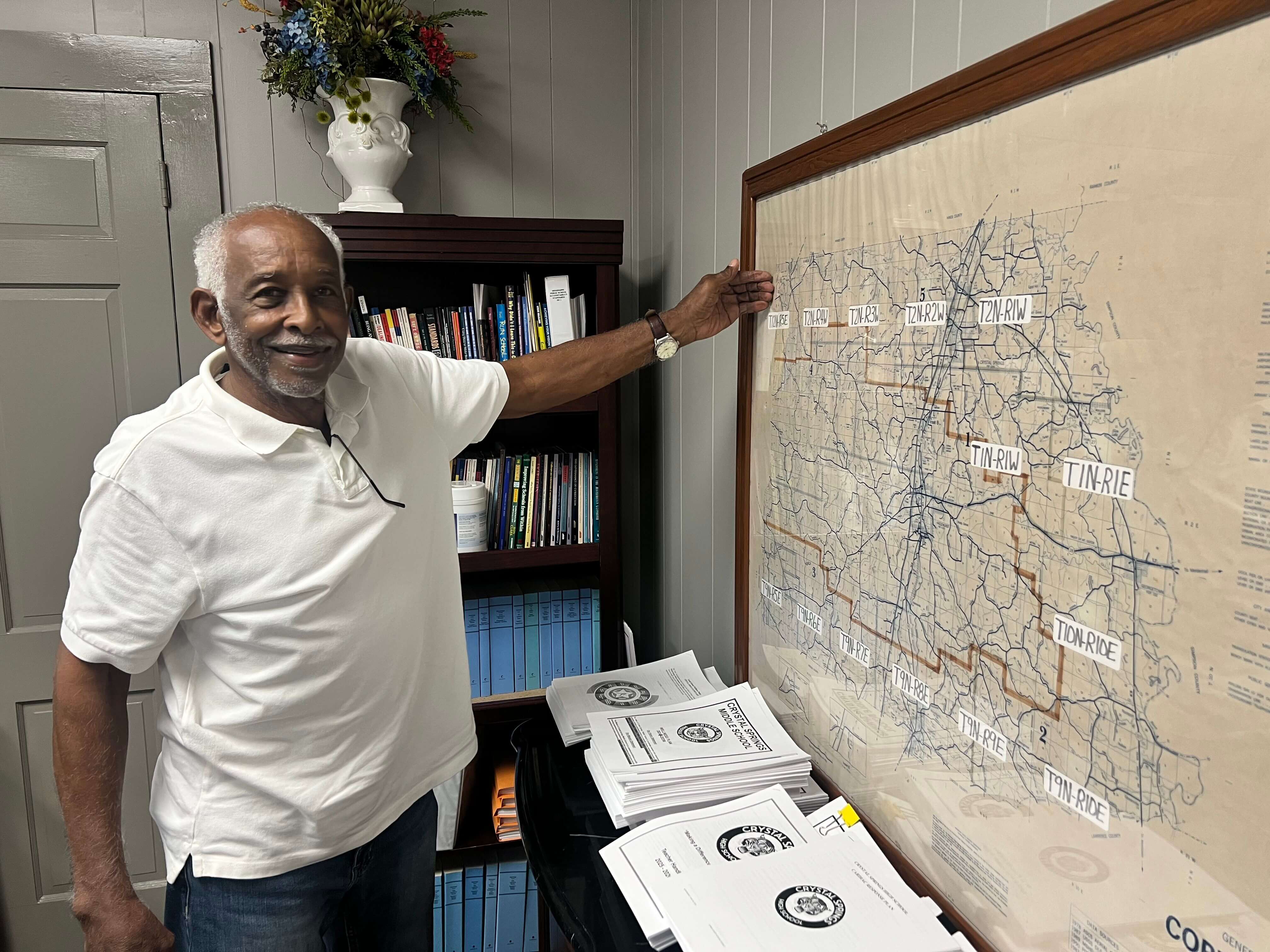

District officials hadn’t visited a courtroom, stood before a judge or escorted DOJ officials around Copiah County’s four public schools in over a decade. Instead, assistant superintendents would traditionally go classroom to classroom to count students and staff by race and the school attorney would write up a report. Facilities and extracurricular offerings at each school were compared. So were yearbook spreads. The documents were slipped into an envelope and sent to a federal judge and emailed every March and October.

The cycle would repeat until the court was pleased.

“ We were trying to justify what we were doing, but it had been very difficult for someone sitting in an office in Washington, D.C., to understand. It was the most frustrating part of the job that we totally understood and totally wanted to comply with but could not,” said Martha Traxler, longtime assistant superintendent with the district. She noted the challenges in particular of recruiting enough Black teachers.

Whether the school district made adequate progress was regular chatter in barber shops and on front porches for decades. Whether in a cafe in Crystal Springs or outside the Stop N Wash in Wesson or sipping on a tea on the patio of Stark’s Restaurant in Hazlehurst, you’re likely to hear a different story with characters depicted as negligent or stretched thin, malicious or doing the best they could with what they’ve got.

But in each telling of the county’s crawl towards progress, some details remain true, some statistics are irrefutable and some comparisons speak for themselves.

The county schools

Copiah County is mostly rural with lush farmland, three quaint towns and one county school district and a separate city school district in Hazlehurst. The county district has a K-12 school to the south in Wesson, which is 73.7 percent white with a student body over 78% white. It also has a high school, middle school and elementary school to the north in Crystal Springs, which is over 65% Black with a student body nearly 80% Black.

Wesson Attendance Center, established in 1960 with a new high school campus built in 1978, has all three schools on one expansive stretch of green bordered by trees. The campus boasts impressive facilities, including a separate baseball and softball field and an indoor basketball court with maple floors.

Until 1978, Wesson students attended high school on the campus of Copiah-Lincoln Community College, whose football field Wesson students still practice and play on.

Crystal Springs High School, built in 1928, stands on the same few acres of land as Crystal Springs Elementary School. The campus has a football field with a track as well as a baseball field. The high school is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A past district administrator, two former teachers, one current teacher and three current students cited their concerns about aging and unclean facilities in interviews with Mississippi Today.

Crystal Springs Middle School is housed in the old Black high school, the William H. Holtzclaw School, which was built in 1958. Now, 67 years later, the campus remains seven single-story brick buildings partly connected by breezeways and bordered by chain link. It’s apparent that the school was built as cheaply as possible, said former superintendent Dale Sullivan. The ceiling supports are a fraction of the size they should be.

It’s also the worst performing school in the district. For the last four years, the school, which had a 2023-24 enrollment of 368 students, has received a “D” on the state accountability system.

On average, while the district spends $179 more per pupil at Crystal Springs’ schools than Wesson’s, Crystal Springs teaches 383 more students.

August 1970

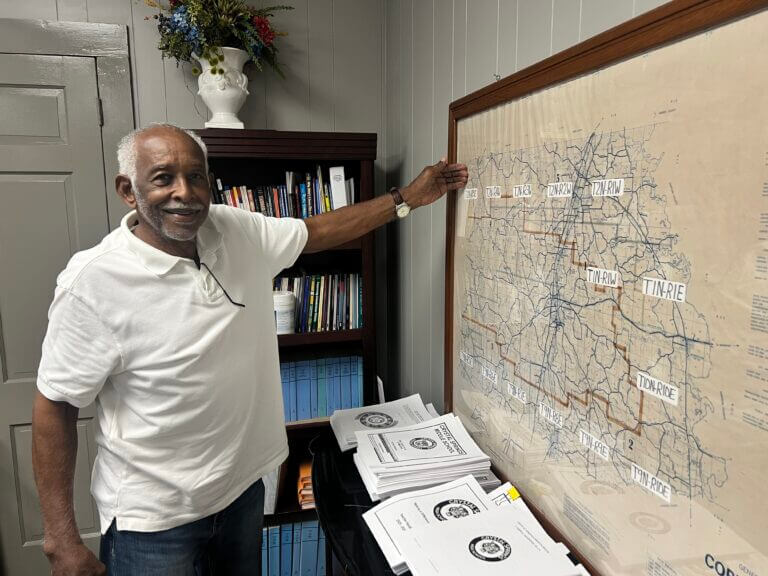

Jimmy Buchanan, who is Black, still remembers the day he became principal of Crystal Springs High School, one of the first integrated high schools in the county. He was recruited at age 28 from the Hotzclaw School for Black students.

“I just assumed that that’s just the way it was. Everything had always been separate that way and they just kept it like it was,” he told Mississippi Today.

School was set to open the following week when the desegregation order came down. Superintendent George Myers delayed school for a week. He called a reluctant Buchanan into his office and offered him the principal position at Crystal Springs. Buchanan was content at Hotzclaw and didn’t want the position but was told he had no choice because there would be no Hotzclaw in a week’s time.

In the days leading up to the first day of school, he was up past midnight working on rearranging schedules for students.

“It was different,” he said. “Because you had whites and Blacks that (had) never been together. And you had white teachers that never taught Black students.”

By the first day of school, enrollment at Crystal Springs High School was 66% Black, the middle school was 71% Black and the elementary school 81% Black. Many white families enrolled their children in Copiah Academy, which had recently expanded after merging with a segregation academy in Crystal Springs in April. Construction on a larger private school was underway.

Buchanan was undermined both by white parents who felt he was favoring Black students because of his race and by Black parents who felt he was favoring white students because of the racial make-up of the district office. They thought he was a token.

For the first semester at least, there were no assemblies. It took enough time and energy for district employees to manage new schedules and bus routes. Black and white students had to be equally represented in each class. Band and football were first reintroduced with an integrated roster.

“The idea was that the less contact these kids had with each other initially until they got used to doing what they were doing, the better. ‘Cause there was always some smart little kid that said something that he shouldn’t,” said Sullivan, who served as superintendent from 1973 to 2001.

The school board attorney went from school to school meeting with parents about “what’s fixing to happen.”

For the first few decades after the order, the district made do with a lot of “co-’s” – a white student body president and a Black student body president, a white homecoming queen and a Black homecoming queen. Even for superlatives like ‘best dressed” and “most likely to succeed” there was Black and white representation.

It was implemented not because of friction but because of what might happen should tensions arise, said Sullivan.

“I would say integration was as smooth as it could have been,” Buchanan said. “It got as integrated as you’re going to get. … At least here.”

Sullivan remembers how some white families were committing fraud to be zoned into Wesson schools, which remained primarily white, because of “housing patterns.” They would move campers to land owned by friends and family in Wesson in time for school registration.

Greg Brock, who was a high school senior then and wrote columns for the local paper, remembers no fights on campus but plenty of tantrums in town. His dad’s auto body shop was boycotted by locals who disapproved of his columns urging people to accept change. He remembers a racist rant from a customer.

In a column at the time for the city newspaper, he wrote “How is school? … What has happened? … How do we like the teacher? … Will it work? These questions and many more permeate the minds of interested persons as the school year of 1970-71 progresses.”

August 2005

In August 2005, the county schools were declared integrated except for staff and teacher assignments. The court order came down during another weeklong school delay with this one brought by Hurricane Katrina.

The storm knocked out power for many residents in Copiah County and destroyed homes. Some students enrolled in schools in neighboring states.

When school resumed, “I don’t think the numbers changed as much as it was more or less accepted among the races that: ‘Hey, Black teachers are not as bad as we thought. They can teach. They’re really knowledgeable. Hey, white teachers, they do care. And they are human beings, too,’” Buchanan said.

The challenge for assistant superintendent Traxler who took on the role of assistant superintendent in 2003 was to find enough Black teachers for predominantly white Wesson. The court order demanded that the ratio of Black and white students in each school reflect the ratio of Black and white teachers at the school.

Traxler traveled to job fairs, visited local high schools and colleges, set up booths at conventions and approved faculty transfers – but the percentages didn’t seem to budge.

Until her retirement in 2016, Traxler experienced a worsening teacher shortage, which made the job of satisfying the DOJ orders more difficult. She struggled to find more than a single qualified math and science teacher at conventions in her later years on the job.

“It was impossible what they asked of us. Even if we transferred teachers over. They mostly didn’t want to commute further. They would’ve chosen another district,” Traxler said.

In the district’s most recent status report for the Department of Justice and the courts, percentages of white and Black teachers at the four schools remained stagnant. District officials were seeing no change. The percentage of Black teachers at Wesson’s schools hovered around 10%.

“The only thing we had left is to balance out the professional staff of our schools without transferring them out from all sides of the county,” said Superintendent Clopton. “It was unrealistic because of the patterns of where people lived and patterns of where people want to work.”

September 2025: Crystal Springs

Crystal Springs High School junior Marissa Marsaw remembers the first time she played Wesson High School in volleyball. She slung her duffel bag on a spare chair and marvelled at the locker room for guest teams. It had clean floors without rat poop and roaches, an entire working restroom, and new-looking lockers.

She couldn’t believe she was in the same school district.

Only 22 miles down Highway 51 from her native Crystal Springs, she encountered a very different city and school. A school where students could partake in a robotics team and a Beta club. She had grown accustomed to fundraising for the athletic teams to cover fees and equipment. Wesson had its own stadium.

Marissa Marsaw said it disturbed her and her mother to learn that Wesson and Crystal Springs hold high school graduations on the same day – and that board members, split along lines of race and geography, didn’t attend the others.

Three current Crystal Springs students expressed concerns about dirty locker rooms and a lack of class trips and extracurriculars like robotics.

“The district gives to who they want to give to,” Crystal Springs senior Alivia Newell said. “I don’t think they want us to be a better school.”

They acknowledge community members are more comfortable voicing concerns online but not in person. It doesn’t help that the Copiah County School District holds board meetings at 3 p.m. on a weekday when most parents and teachers are still at work and students are just getting out of class.

Marsaw and her friends gather at Book Street Cafe in downtown Crystal Springs some days after school. They interact with classmates from not just the local high school.

Greg Brock, the proprietor and a former New York Times and Washington Post editor, bought the cafe last year after moving home. He had gotten his start as a student journalist at the city paper and covered integration and its aftermath.

Mid-to-late afternoon on a weekday, his cafe boasts a lively clientele that pretty much represents the diversity of the city. Teens pull books from the shelves and sip on colorful refreshments and frappes.

It’s meaningful for Brock who believes the death of the city came with white flight.

“They wrote that school off,” he said of the Crystal Springs schools. “That’s the day this town started dying. When whites started abandoning it.”

September 2025: Wesson

Across the county, in Wesson, locals had been congregating at Wash N Stop for years. From the outside, it resembles an ordinary gas station convenience store with a regular crowd of commuters and townies. It’s the most active parking lot in town.

To many in Wesson, Larry Ashley is best known as the proprietor of the convenience store that serves mouth-watering fried chicken and potato wedges. Ashley also builds homes with the help of his son.

Ashley, who has lived in Wesson most of his life, switched to Hazlehurst City School District from Wesson his junior year but was recruited to join Copiah Academy’s football team his senior year. He went on to attend Copiah-Lincoln Community College and graduate from Mississippi State University.

“I think Crystal Springs has all the same things that Wesson has school-wise,” Ashley said. “But they’re starting a hundred-yard dash with 10 kids that have to run an extra 10 yards to get to the finish line. So what does a teacher have to do? A teacher has to lower her standards.”

For mom Barbie Stroud,who is white and new to Wesson, the decision to home school while her family lived in Crystal Springs was easy.

“The schools are just not the same,” she said.

She feared school fights that she heard about in Crystal Springs and Hazlehurst would endanger her child’s wellbeing. She didn’t want her child around purported gangs in those communities.

At Crystal Springs High School, nearly 44% of the student population was suspended in 2023-2024 with 45 violent incidents reported. Less than 10% of Wesson Attendance Center students were suspended the same year with 12 violent incidents.

One has double the chance of becoming a victim of violent crime in Crystal Springs than in Wesson, though a majority of crimes reported are property crimes.

Wesson is a town where, in the words of one resident, “the most common crime is speeding tickets and residents keep each other accountable on Facebook.” Public school teaching posts are hardly vacant because a majority of teachers are from the community.

“I wouldn’t drop my kid by himself at a football game there on a Friday night,” Stroud said of Crystal Springs.

Crystal Springs has some extracurriculars that Stroud wants for her child, such as JROTC and more vocational classes.

Blake Allen, a Wesson graduate and musician, said the problem is that the accountability system used by Mississippi public schools incentivizes teachers to raise the bottom 25 more than work with the middle 50 or top 25. He feels his kid wouldn’t get the same attention in a Crystal Springs classroom where many more students are starting off with less knowledge.

He also said Wesson’s facilities seem nicer.

“There’s probably more favoritism towards Wesson,” Allen acknowledged.

A ‘cultural difference’

When asked whether the schools in Crystal Springs and Wesson are similar in quality, Copiah County residents and stakeholders held up statistics, rattled off anecdotes and shared photos of leaking roofs.

Among Crystal Springs students, 34% on average enroll in college and 31% take an advanced placement course in high school. Among Wesson students, 77.6% enroll in college and 63% take an advanced placement course.

Wesson is an “A” school. Crystal Springs High School is a “B” school.

Kenneth Thrasher, who is Black, remembers a tense conversation with administrators in the central office about a transfer for his high-achieving daughter from Wesson to Hazlehurst School District. They wanted him to keep her there.

But he felt a “cultural difference” at Wesson. He was getting messages from a teacher he felt didn’t have experience teaching enough Black students. The teacher scrutinized his daughter’s knack for dancing when popular music was played in class. He also didn’t like that she was a minority in the classroom.

The decision to enroll her in Hazlehurst wasn’t hard.

“I had seen the last Confederate flag fly in the line-up at parent pick-up,” he told Mississippi Today.

Asked whether the Copiah County School District successfully integrated to the extent there isn’t a noticeable Black school and white school, a majority of the more than a dozen local residents surveyed by Mississippi Today said no.

Crystal Springs has the Black schools in the district and Wesson the white ones, they said.

“We are all prejudiced,” Ashley said. “Because if I walk into a football game, you got families, mama, daddy, Black, white, Mexican, whatever, sitting in the middle section. And in another section you’ve got Black looking thugs, dreadlocks, all this stuff. I ain’t saying they’re bad people. You got white tattooed out all over their faces and all this thug looking white guys over here. And I’ve got my 9- and 10-year-old daughter with me. Where am I going to sit? I’m going to choose the family section in the middle. Is that prejudice? Maybe so, but I’m still going to choose it.”

Mississippi Today also asked stakeholders whether moving a certain percentage of Black teachers to Wesson changed the dynamic in the county between the races and community schools.

A majority of school officials said it would be hard to say.

“A part of me felt that I didn’t achieve the goal that I set out to achieve, which was to get everyone to love our school as much as I did,” said former assistant superintendent Traxler. “I’d like to say I can’t change hearts. Only God can do that.”

Correction 9/16/25: This story has been corrrected to change the name of the school Kenneth Thrasher’s daughter transferred to.

- State fire marshal is investigating troubled Unit 29 at Parchman prison - February 26, 2026

- Mississippi’s Winter Storm Fern losses exceed $107 million, state insurance department says - February 26, 2026

- DNA evidence linked to a Greenville homicide is missing. Now the finger-pointing begins - February 26, 2026