Twenty-seven percent more rape kits were sent to the state crime lab in 2024 than the year before in Mississippi.

The increase is thanks in part to a law passed in 2023 to streamline rape kit processing, which officials say resulted in more rape kits making it to the crime lab. However, because Mississippi has no complete rape kit inventory, it’s impossible to tell what impact it made on the backlog.

While variation from year to year is normal, the crime lab has not seen an influx that large in previous years – likely signifying the legislation’s effect, explained Commissioner Sean Tindell of the Department of Public Safety.

But Tindell added that he could not say how many kits, if any, are still getting stalled along the way.

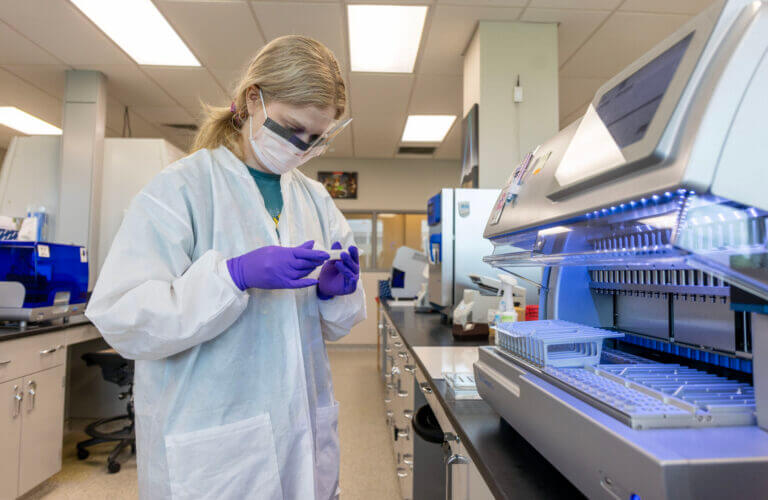

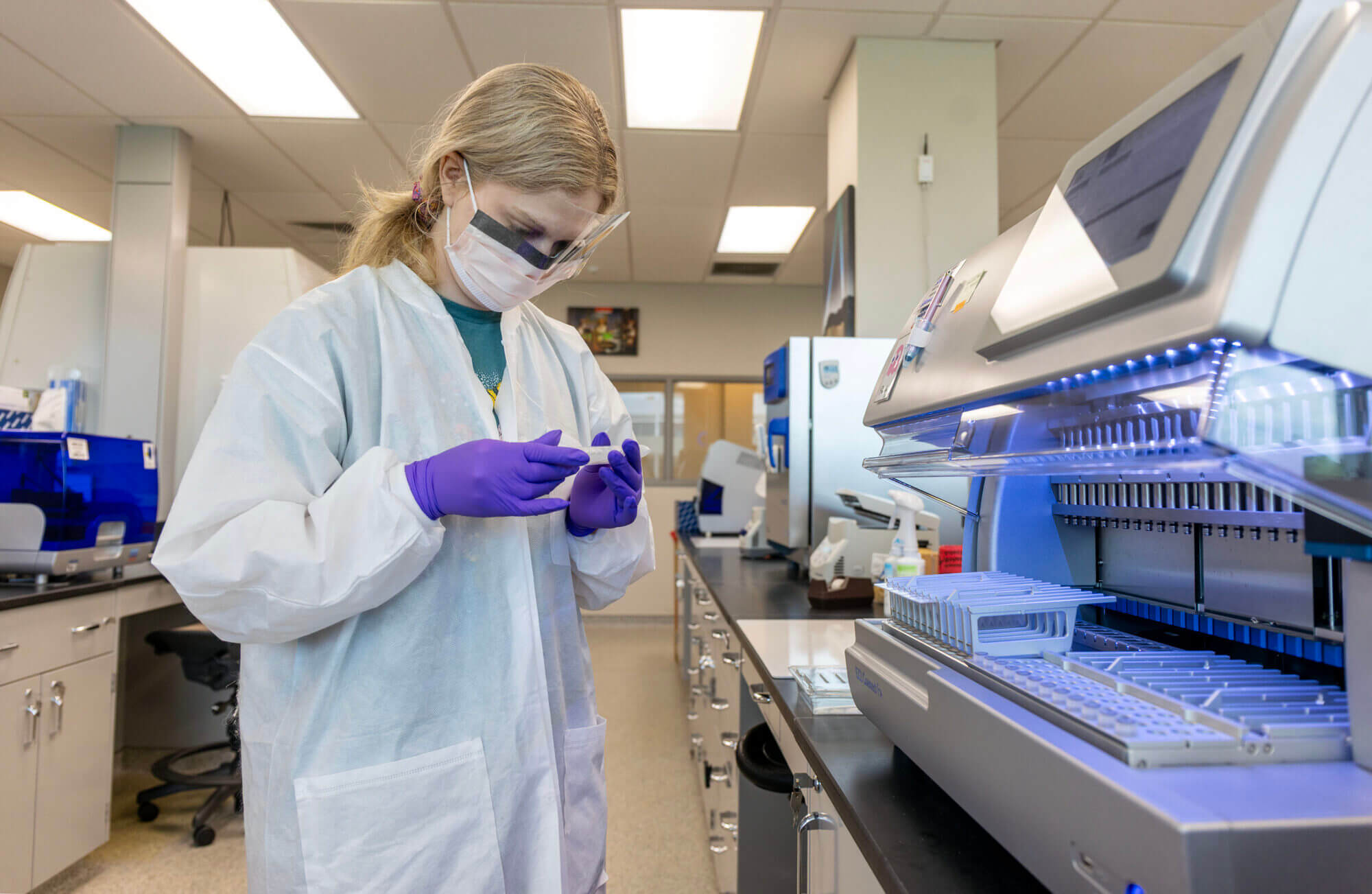

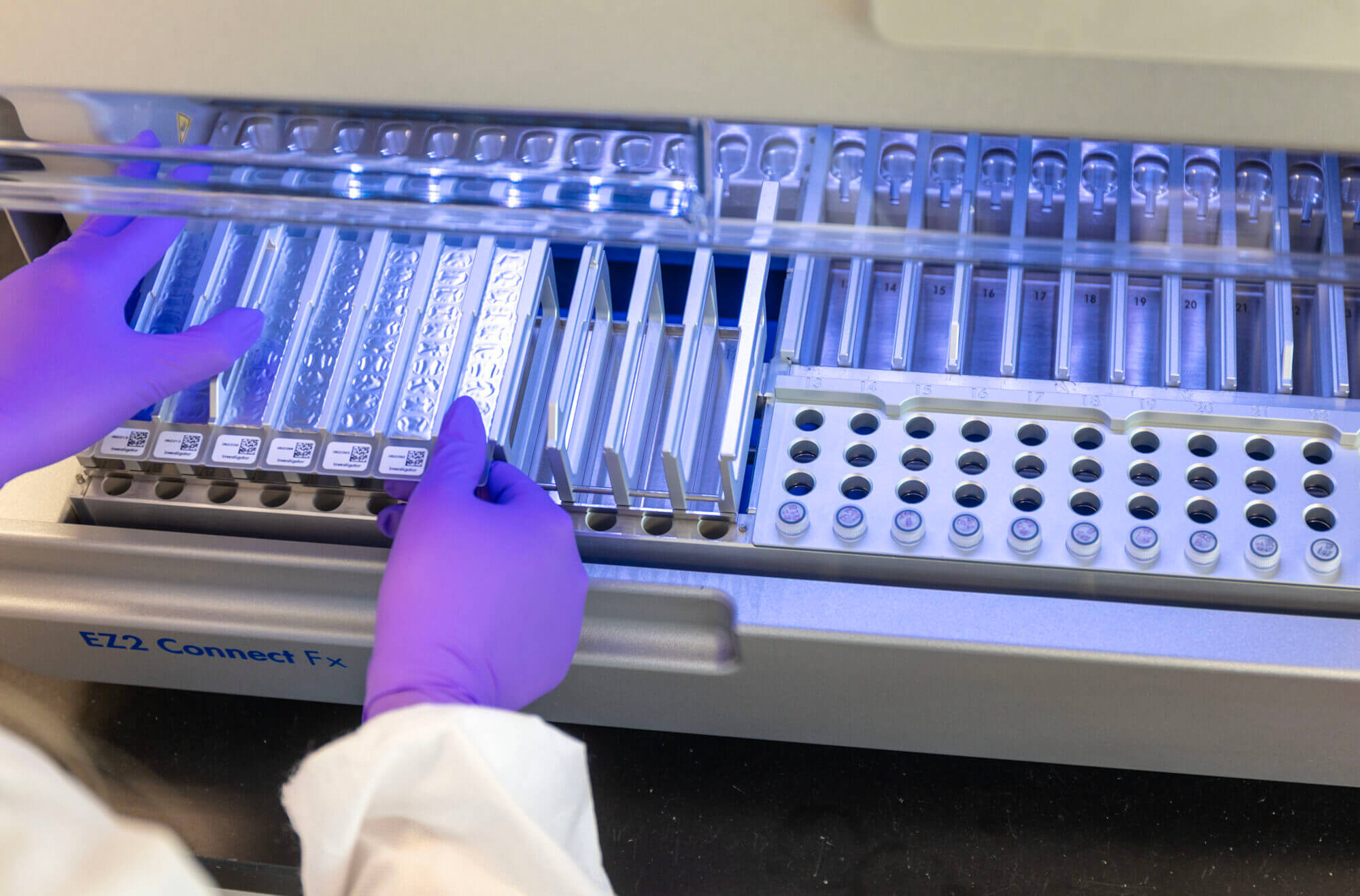

House Bill 485 mandated law enforcement pick up rape kits from hospitals within 24 hours of being contacted, and that they transport the kits to the forensic lab within seven calendar days. It also created a sexual assault task force, whose members designed a system for survivors to track their rape kit as it changes hands.

The tracking system went into operation September 2024, Tindell said. Any rape victim who had a kit done after then can track the status of the kit by putting its serial number into the online system.

The idea was that rape kits could would no longer sit indefinitely in hospital refrigerators or in the trunks of cop cars, and that survivors would be kept in the know – the way patients are for any other hospital procedure.

“They leave the hospital and they don’t know where their kit is, they never hear anything. Can you imagine getting a cancer test and nobody ever calls you back to tell you what it was? For months or years or ever?” asked Ilse Knecht, policy director at End the Backlog, an organization seeking justice for sexual assault survivors through policy work around rape kits.

Backlogged rape kits have long been problem across the U.S. – one that first sparked public outcry in 1999 when it was discovered that New York City was sitting on 17,000 untested rape kits.

“What happened later was that the mayor decided to test them all, which was a years-long process, and there were very important and interesting cases that came out of that,” explained Knecht. “And it started to catch on, the other states started to look at what they had. And we started to get a sense of what was going on across the country.”

The root of the problem isn’t as simple as underfunded crime labs or a lack of resources in law enforcement agencies, Knecht said. It’s also a matter of culture, with some kits never being tested because victims aren’t believed.

“If they’re not the perfect victim, the case is going to be closed before it’s even opened.”

The Mississippi Prosecutors’ Association did not respond to a request for comment on whether the increase in submissions to the crime lab has led to an increase in prosecutions.

Knecht, who has 25 years of experience working in this area, joined End the Backlog in 2015, when she helped develop the group’s policy directives. After collaborating with dozens of sexual assault survivors and various professionals handling rape kits, her team came up with six pillars intended to guide states toward policies to enact meaningful and feasible change.

Mississippi’s 2023 legislation led to the adoption of three of the six pillars End the Backlog recommends: mandating the timely testing of all new kits; implementing mechanisms for survivors to easily find out about the status of their kits; and creating a tracking system for victims.

The other three pillars, which Mississippi does not have, are: implementing an annual statewide inventory of kits; mandating submission and testing of all backlogged kits; and allocating funding to submit, test and track kits.

The timeline the 2023 legislation imposed on law enforcement is more than reasonable, according to Ken Winter, executive director of the Mississippi Association of Chiefs of Police.

“It absolutely has not taken more staff or resources,” Winter said. “The only thing it’s taking is somebody paying attention to the process and making sure the evidence is handled in a timely manner – and they should be doing that anyways.”

House Bill 485 was a bipartisan effort led by Rep. Angela Cockerham, I-Magnolia, and co-authored by Reps. Dana McLean, R-Columbus; Jill Ford, R-Madison; and Otis Anthony, D-Indianola.

McLean said she believed the legislation was the first step to getting justice for sexual assault survivors.

But she later became aware that some rape victims have trouble earlier in the process – getting a rape kit done in the first place. McLean fought to change that this past session, and successfully oversaw the passage of a bill requiring hospitals to stock and perform rape kits.

What makes the problem still more complicated in Mississippi – and four other states – is that the state has not mandated an inventory of rape kits. There is no way to tell the extent of Mississippi’s backlog – or at what point in the process the kits are getting backlogged.

McLean said she hopes to make a mandatory statewide inventory her focus next legislative session.

The issue is dimensional, said Knecht. But the message of the movement is simple: to tell survivors that what they did by receiving a rape kit mattered.

“All of this was created to keep a promise to survivors,” Knecht said. “And to society because guess what – these kits represent dangerous people on the street. And when they’re not tested, we have 100 pages of stories of crimes that maybe could have been prevented if a rape kit had just been tested.”

The post Crime lab sees increase in rape kits following new law appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Scott Colom raised most money, but Cindy Hyde-Smith has most cash before March primary - February 21, 2026

- Patients face canceled surgeries and delayed care amid UMMC cyberattack - February 20, 2026

- Goal is ‘better alignment, not bigger government’ for Mississippi tourism - February 20, 2026