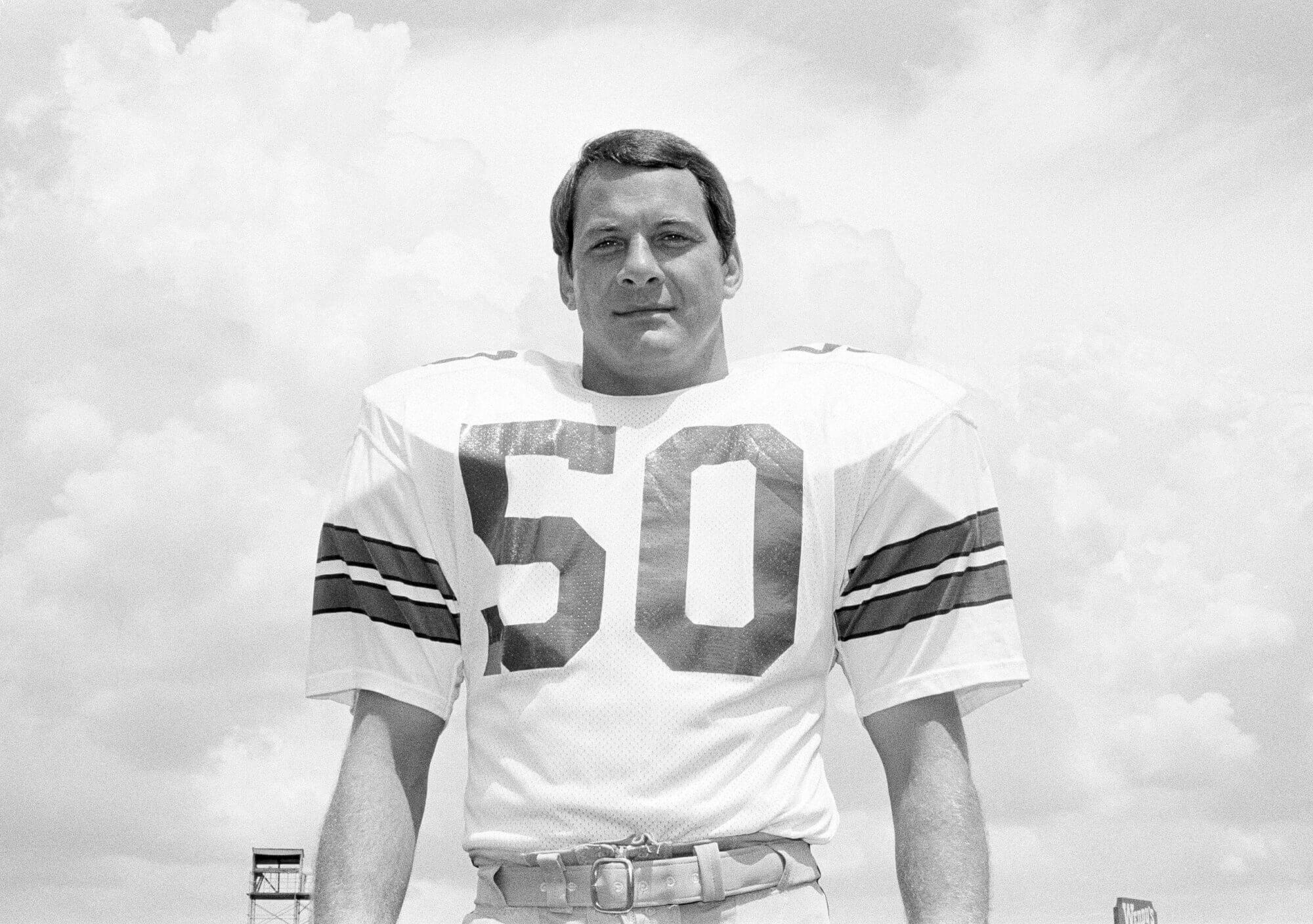

D.D. Lewis, the great football linebacker, will be remembered at Mississippi State as one of the university’s most beloved athletes who happened to play on some of the school’s most abysmal teams. He died on Sept. 16 after being hospitalized for 12 days in Plano, Texas. He was 79.

In 1967, playing for a State team that did not win a single SEC game and lost nine of 10 overall, Lewis was named the SEC’s most outstanding defensive player and a first-team All American. He really did not make every tackle. It just seemed that way.

There was some football justice for Lewis. After playing for such dreadful teams at State, he was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys, the so-called America’s Team for whom he became a cornerstone of their famed “Doomsday Defense.” He played in five Super Bowls and earned two Super Bowl rings. Overshadowed by linebacking teammates such as Leroy Jordan and Chuck Howley, Lewis never made the Pro Bowl. Legendary Cowboys coach Tom Landry, upon his retirement, called Lewis “the most under-appreciated player” in Landry’s 29 years with the team.

But D.D. — a good and treasured friend to this writer — was so much more than that. He was a charming man who oozed charisma, despite admittedly battling inner demons for much of his life. He was the 14th of 14 children who grew up in poverty in the area of north Knoxville, Tennessee, where many families from Appalachia settled.

Born a month after the end of World War II, D.D. was named for two American heroes of that war: Dwight Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur. His was not a happy childhood. He was abused, both physically and mentally, as a young boy.

“I stayed in trouble, both at school and at home,” he once told me. His mother once told him there was no use in doing his homework because he was never going to amount to anything. As a young teen, he was arrested more than once.

D.D.’s path out of all that was football.

“Seems as long as I can remember, I was always striving for attention,” he told me in 1988. “I was a problem student, always getting into trouble and running with the wrong crowd. For a long time, that was my way of getting attention.”

Then he found football. Football was his way out. Hitting people — hitting them really hard — brought him acclaim. At Knoxville’s Fulton High, he gained the attention and status his mother had told him would never come. His name was in the newspaper headlines. Sportscasters raved about him on radio and TV. College coaches recruited him. They praised him. They wanted him. For the 14th of 14, that meant so much.

Paul Davis, the head coach who successfully recruited him to Mississippi State, would later call him “the best linebacker I have ever seen.”

But here’s the thing: The more praise D.D. received, the more he feared losing it, the more he feared failure. And that drove him to be better, to hit harder. He told me he had a recurring nightmare.

“I’d be playing linebacker and a big hole would open up in the line,” he said. “And here’d come the running back, and he’d just flatten me.”

That rarely if ever happened in real life. D.D. was a tackling machine. When he retired from the Cowboys at age 36, he had reached the playoffs in 12 of his 13 seasons. He had appeared in 27 playoff games, an NFL record at the time. Indeed, even today, only Jerry Rice and Tom Brady have played in more playoff games. Peyton Manning, too, played in 27.

D.D. was at his best when it mattered most. In a 1975 NFC Championship victory over the Los Angeles Rams, he intercepted two passes. He had four interceptions total in playoff games, the most ever for a linebacker.

Sports writers loved him because he was so honest, such a good quote. Indeed, D.D. was the guy who said, “Texas Stadium has a hole in the roof, so God can watch his favorite team play.”

D.D. could tell a story, too. He once told one about Dandy Don Meredith, the Cowboys quarterbacking star who later sparred with Howard Cosell in the ABC Monday night TV booth.

“We were on a flight back from New York after beating up on the Giants,” D.D. said. “Drinks were flowing. Everybody was having a good time. And then we hear this loud explosion outside the plane, and the plane starts bucking and then the lights go on and off. The stewardesses were crying. I look around and some of our players are crying and some are praying. And then I looked across the aisle at Dandy Don, and he’s smiling. He took a big swig of his drink and then a big drag off his cigarette and said, ‘Well, boys, it’s been a good ‘un.’”

Of course, the jet eventually landed with one good engine, and D.D. enjoyed a pro career in which he never experienced a losing season. He was dependable and he was durable. He missed only two starts because of an injury. He played through aches and pains that would have sidelined most. He retired in 1981, mostly because there wasn’t a joint in his body that did not hurt. After 26 years of football, beginning with peewee ball at age 10, the whistles quit blowing and the “high” of competition, of victory and championships and all the glory that came with it disappeared. His identity had been football, and football was gone.

D.D. was lost. Years later, he would tell me he replaced the “highs” of football with alcohol and pain-numbing drugs.

“It wrecked my life, it wrecked my marriage, it almost wrecked my relationship with my two daughters,” he said.

It didn’t help that the business he entered after football — the booming Texas oil business — went bust. He was broke. He even sold some of his Cowboys memorabilia, including his last helmet, to pay some bills.

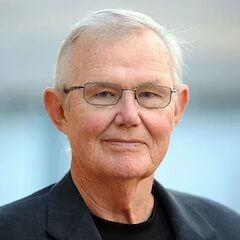

“I am a lucky man,” he told me before his 2001 induction into the College Football Hall of Fame. “I got sober. I found the church, and there I found the Lord.”

He also reunited with an old college sweetheart, whom he married and settled down with in more ways than one.

“People ask me if I am sorry that I missed all those years with D.D. when he was a big football star with the Cowboys and all that,” Diane Lewis, his second wife, said. “No, I’m not. The D.D. I married was a loving, sober, God-fearing, gentle man. He wasn’t always that.”

D.D. became a fertilizer salesman who traveled the roads of central and east Texas, selling something his customers really needed.

“I’m a shit salesman now,” D.D. once told me. “If you’re going to be a shit salesman, be a good one. I try to be.”

He told a story about one of his customers, a farmer who did not recognize him from his football days. They became good friends. Later on, the farmer was astounded to learn that his friend had once been a big football star for America’s Team. D.D. had never told him. D.D. never tooted his own horn.

“The man liked me because I was D.D. the fertilizer salesman, not because I had played in Super Bowls with the Dallas Cowboys,” he said. “You can’t imagine how much that meant to me.”

- State fire marshal is investigating troubled Unit 29 at Parchman prison - February 26, 2026

- Mississippi’s Winter Storm Fern losses exceed $107 million, state insurance department says - February 26, 2026

- DNA evidence linked to a Greenville homicide is missing. Now the finger-pointing begins - February 26, 2026