The Rev. Jeff Hood is “determined to let people know you’re killing my friend.”

Those are the people he’s grown close to before witnessing their executions — a dozen so far and a number that continues to grow as Mississippi prepares to put 79-year-old Richard Jordan to death and the death penalty continues being handed down in over half of all states, particularly the South.

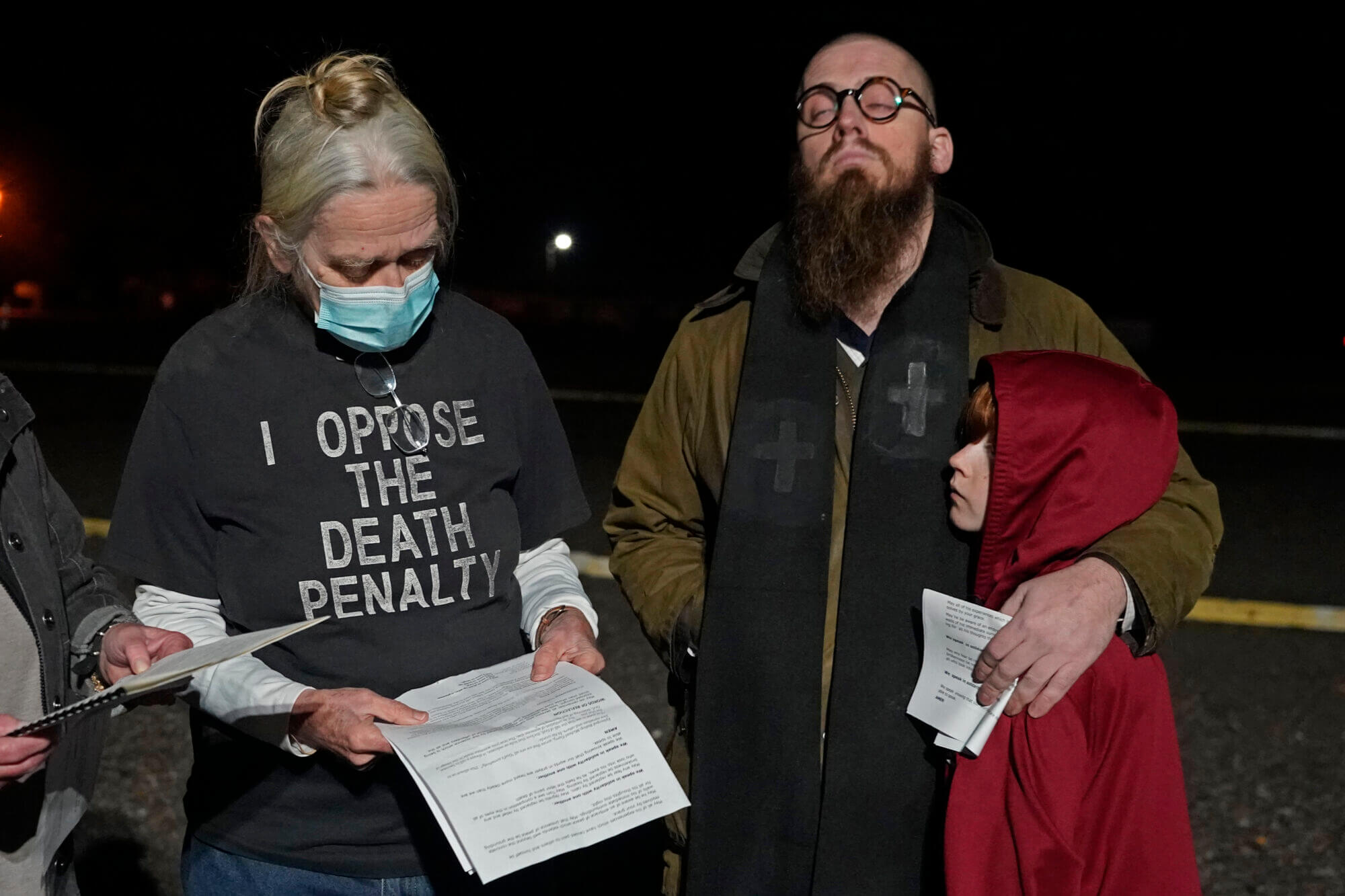

Hood is a spiritual adviser who accompanies death row inmates to their executions, praying for them and sharing last words with them as a culmination of a months-, sometimes years-long relationship.

By doing that, Hood said he can bring members of the public as close to the execution chamber as they can get and see the impact of the death penalty.

To date, he has witnessed 11 executions: four in Oklahoma, three in Alabama, two in Texas, one in Missouri and one in Florida.

It’s something he may be called to do one day in Mississippi. Hood is not Jordan’s spiritual adviser, but he has communicated with a member of Jordan’s family and he plans to travel to Parchman to pray outside on June 25 if Jordan’s scheduled execution goes through, just as he did in 2022 for the execution of Thomas Loden, a Marine Corps recruiter who kidnapped, sexually assaulted and killed a 16-year-old waitress.

He and advocates have spoken out against Jordan’s scheduled execution, questioning whether it makes sense to see someone who is almost 80 as a safety risk and the fact it’s been 48 years since he was first convicted of capital murder in the kidnapping and death of Edwina Marter in Harrison County.

He participated in a video released by the Mississippi Office of Capital Post-Conviction Council in which Jordan shares his story and asks the state to commute his sentence to life without the possibility of parole. In the video, Jordan says he was a model citizen until he returned after three tours in the Vietnam War. His defense has argued that he suffered post-traumatic stress disorder from the war, a view bolstered on the video by Jordan’s younger siblings — brother Houston Jordan and sister Nordeen Jones — who said he was kind and a role model to them. Former schoolmates, ministers and a retired corrections officer also appear on the video, talking about Jordan’s willingness to help others.

‘Whatever you did to the least of these’

Hood grew up in Georgia in a Southern Baptist family and studied theology. As he studied in Atlanta, he was part of organizing against the 2011 execution of Troy Davis, who maintained his innocence to the end in the murder of a Savannah police officer.

Connecting with death row inmates and being present at their deaths is something he said he was called by God to do, saying the work aligns with Matthew 25:40: “(W)hatever you did for the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

Hood can’t think of a group that embodies “the least of these” more than those sentenced to death. He said he shows them the love of God and encourages them to have the courage to live, even if they have weeks or months left and people want them to be executed.

“It’s my job to make them hungry to live,” Hood said. “I think that is the greatest resistance possible.”

Innocence isn’t a requirement to work with someone, and he said he will love someone “irrespective of what they’ve done.” But Hood said that doesn’t mean there haven’t been difficult interactions or that he doesn’t think about victims’ families and the severity of death row inmates’ crimes.

Hood sees how nearly 50 years of waiting for an execution has been torture for any victim’s family, especially the Marters.

Eric Marter, the elder son of Edwina and Charles Marter, was 11 years old and his younger brother was 4 when their mother died.

He said it’s been so long and he would have preferred Jordan to have been executed years ago. Over the years of his appeals, Marter said he hasn’t made his ongoing legal case and whether an execution happens a priority.

“At this point in my life, maybe 30 years ago I may have had more interest in wanting him to be executed,”said Marter, who is 59 and lives in Louisiana.

“But at this particular point, I don’t really want to waste my time thinking about him.”

A ‘moral sacrifice’ to be in that chamber’

Spiritual advisers like Hood have been allowed to be in the room and stand alongside the condemned since 2022, when the U.S. Supreme Court agreed with a Texas death row inmate who sued for the right to have his pastor beside him.

June 10 was the executions of Anthony Wainwright in Florida and Gregory Hunt in Alabama. As both of their spiritual advisors, Hood said the states put him in a position to have to choose whose to attend and break a promise. He was with Wainwright at his execution.

The week before that, he was on the road and traveled from his home in Arkansas to Alabama and Florida to be with the men and organize against the death penalty with local advocates. From a virtual event streamed from his car June 6, Hood raised issues about violations of Hunt’s and Wainwright’s spiritual liberty and constitutional rights.

Like Mississippi, most death penalty states use lethal injection, but others are starting to use lethal gas and firing range. Since 2022, Mississippi allows those methods along with the electric chair, but lethal injection is the state’s preference.

Jordan continues to challenge the constitutionality of the drugs Mississippi uses for lethal injection through a federal lawsuit.

Last year, Hood witnessed the “horror show” execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith in Alabama by nitrogen gas. The pastor remembers seeing Smith start to heave back and forth violently as soon as the gas hit his face, his veins looking like ants under his skin. Smith thrashed against the restraints, and Hood remembers crying – something not typical for him.

Even if an execution has not been scheduled, Hood stays in contact with two dozen people on death rows around the country. Some call him several times a week and on specific days.

His contact includes seven in Mississippi, including Willie Manning – for whom the state is seeking an execution date – and others who are still pursuing legal challenges such as Willie Godbolt and Lisa Jo Chamberlin.

Chamberlin, convicted of two counts of capital murder in 2006, is the only woman on death row in the state, and Hood said he reached out to her knowing a bit about her story and that she needed help. What he found was someone who “desperately needed a friend” and whose mental health suffers because she is isolated.

Unlike death row in Parchman where most of the men are together, Chamberlin is kept on her own in a maximum security unit in the women’s prison at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility. Hood said that often means Chamberlin spends hours in her cell or time in the dayroom on her own.

Ahead of Jordan’s execution, Hood has called out elected officials like Gov. Tate Reeves, Attorney General Lynn Fitch and justices of the Mississippi Supreme Court for allowing executions to happen but not having to attend or witness them.

“There’s a moral sacrifice it takes to be in that chamber,” Hood said.

When he stands beside the condemned, Hood prays and tells them how sorry he is that he wasn’t able to stop the execution. And each time he leaves, he said it’s as if he leaves a piece of his soul behind.

The next execution might be scheduled in a matter of days, weeks or months, so he doesn’t have much time to recover. Continuing to intervene in executions and speak out against the death penalty also makes him the target of threats and potentially puts his family at risk. Hood is married and the father of five children.

But Hood takes on the risks to his wellbeing and health and sees it as a privilege to work with people on death row and do something he cares about.

“The spiritual adviser can either be silent about what is happening,” he said. “… (Or) they can speak up and resist the evil that is happening.”

- Mississippi Marketplace: data center ups and downs, alcohol shortages and new manufacturing projects - February 19, 2026

- More Mississippi students are graduating despite pandemic-era disruptions, new data shows - February 19, 2026

- Education advocates says Mississippi needs honest, nuanced school choice discussion - February 19, 2026