Mississippi Delta socialite Tonia Sims-Bush was escorted by an aunt and friends as she walked up the white marble steps of the Leflore County courthouse. Her burlap-hued dress billowed in the hot wind, carved wooden disc earrings swayed from each lobe, and black mascara lent her stony expression considerable intensity.

She was there Aug. 11 for a hearing that could change the outcome of what she perceived as a great personal tragedy: her daughter’s loss of a homecoming queen election.

“We want the truth,” Sims-Bush wrote on Facebook. “The district is fighting to keep the facts surrounding the results hidden.”

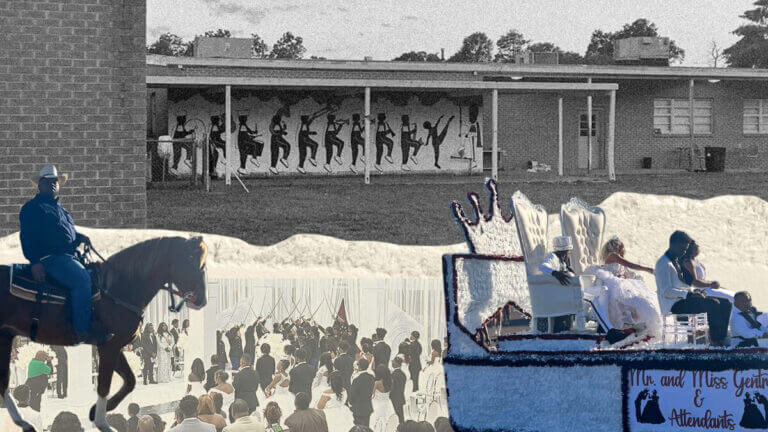

Indianola’s Gentry High School, where Sims-Bush’s daughter is a student, has been holding elections for homecoming queen, or Miss Gentry, since 1954. Recent celebrations included programs printed on metallic foil, two grand thrones moved to the center of a gymnasium festooned with candelabras and chandeliers, rented luxury cars to ride through the annual homecoming parade and a military salute performed by the JROTC befitting a monarch of a lesser but no less grand principality. All this to say, contestants “show out,” in the words of a former school administrator.

But it still came as a surprise to current administrators, when they were sued for $100,000. The accusation against them: stealing a homecoming election for a beloved teacher’s daughter.

Sims-Bush had previously lent her event-planning talent to the school. She decorated a loft space with silver balloons and floats inspired by awards shows for last spring’s prom.

Seven years ago, Sims-Bush transformed the school gymnasium into a medieval courtyard with hedges, gold-colored chairs, sod and a fortress cutout. It was for her elder daughter’s homecoming queen coronation. In 2023, she had changed the gymnasium into an enchanted forest with jungle vines, jewel-toned chairs, fake myrtle trees and a backdrop reminiscent of the forest from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

For 10 years, Sims-Bush has run her event-planning company in the Mississippi Delta. She has hosted galas requiring black tie attire for male attendees and floor-length gowns for female guests. At one of her more recent events at Harlow’s Casino in Greenville, hundreds of guests crowded into a banquet hall for Havana Nights, which featured a cigar bar and performances by fire dancers and contortionists. Guests included local mayors and university administrators.

Her social media account conveys the impression of a well-connected and highly organized professional.

“She appears to have it all,” said one current teacher on staff, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation at work.

But not quite all.

‘Who will win the throne?’

At Gentry High, the morning announcements in late April heralded the call for nominations for homecoming court. Teachers and administrators gave out handouts with nomination guidelines. Students probably had been mulling a run for homecoming queen much earlier, though. For the confident few, it meant ordering campaign banners and forming a winning strategy with parents and friends since at least February.

“Who will win the throne? What can you do to stand out from the rest! Well … this year we shall see! WELCOME to an unforgettable year of campaigning. Below are the guidelines for this year’s battle,” read Gentry’s handout for 2025 homecoming court elections.

Between hosting Thirsty Thursday, Wine Down Wednesday and more banquets for adults, Sims-Bush found the time to manage her younger daughter’s campaign for the homecoming tiara.

In a professionally produced campaign video released May 12, Sims-Bush’s daughter struts by the campus’ exterior in three separate couture looks.

“A brand isn’t just a logo, a slogan or a catchy name,” she says. “A brand is a promise. I don’t want to just wear the crown, I want to carry the responsibilities that come with it. When you cast your vote, you’re not just choosing a queen, you’re choosing a brand of leadership that’s committed to you.”

Sims-Bush also posted reels from six past homecoming queens entreating followers to cast their votes for her daughter.

“That experience did not only give me the opportunity to wear a crown,” the 2016-2017 queen said in one. “It showed me the importance of character, respect and school spirit.”

Before school started on April 14, a pop-up shop went up in the gym. The bubble gum pink store with glass cases featured free custom hats, tote bags, reusable cups and goodie bags – all stamped with Bush’s homecoming campaign logo: a “V” and “K” in a sleek font reminiscent of luxury branding.

Sims-Bush arrived on campus each day of the campaign to help set up a new booth. Wednesday it was a Milan-inspired eatery featuring freshly made pizzas and a Kermit-green float. Thursday it was a Chanel-themed mixer with lunch boxes stamped with the designer logo and a shelf of pink-colored mocktails. Friday it was a “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”-inspired buffet. Dozens of strawberries and madeleines covered a table offering muffins from stands.

On the Friday before voting ended, students and faculty departed their classrooms to see homecoming queen candidates show their talent. A majority of contestants danced to popular music, gyrating in leotards and street wear.

Sims-Bush’s daughter hosted a fashion show with the help of at least 16 classmates. The event boasted a runway and two lines of chairs on either side for spectators. The bass thumped as the teen pageant queen hopeful sashayed down white carpeting in what appeared to be a pink ostrich feather skirt.

Students left school that Friday with goodie bags from her of hot fries and custom tees. Voting would continue through the weekend.

Sims-Bush said she felt Latoya Henry, the teacher monitoring the campaigns, and Lilly Hamilton, a popular Gentry High teacher, were too friendly. Hamilton’s daughter was the other leading contender.

She expressed her concerns in a series of emails she began writing on the second day of campaign week.

“For a parent to walk into a school and feel the hate is absurd. Henry called me ‘one sided brain’ and stormed out of a meeting because I asked her to provide a set timeframe for activities during campaign week,” Sims-Bush wrote.

“The expectation was for other parents to dumb down their displays to match the basic lackluster display of her friends,” she wrote. “We have been treated so ugly all because of thinking outside the box and campaigning.”

‘The national election doesn’t even take a week’

As early as Tuesday of campaign week, Sims-Bush said she began to doubt the integrity of the upcoming election.

“The voting system is as air tight as we can get it,” replied Superintendent Miskia Davis in an email. “No school or district staff member other than Mr. Jones, a 32 year old white guy from New Jersey has access.”

It was Dylan Jones, that 32-year-old white guy from New Jersey, that Tonia Sims-Bush figured was the mastermind of a scheme to defeat her daughter. She was wary of the Google Form used for the election and the tech-savvy data director monitoring the elections.

She wanted paper ballots.

“While we understand the desire for a process that feels traditional, the reality is that digital voting is vastly more secure, more transparent, and more auditable than paper ballots,” Jones, federal programs and data director, wrote in a handout to parents and staff.

Google’s security software would flag adults who tried to vote with a student email address by identifying the login address and device, he reassured parents in the handout.

Before 7 a.m. the Saturday after campaigning drew to a close, Sims-Bush emailed Davis detailing a conspiracy to steal an election for her daughter’s opponent.

“A 5 day voting window is insane,” she said in an email. “No one had given any good reason why a five day voting window over the weekend is necessary for a student campaign except to cheat.

The voting had been done on Google Form over the course of several days for at least the past two years.

She convinced Sunflower County Circuit Clerk Carolyn P. Hamilton to process votes in place of the Google Form method, which was already underway.

“Prior to the voting, she contacted me and asked if I could do the voting process instead of the students using Google [Forms]. I informed her that the timing would be tight but if I worked through the weekend I could get it done. I also told her that the School Board will have to approve it before I do anything,” she wrote in a statement to Mississippi Today.

“This would be a one-day process not five,” she stressed.

‘The Cadillac version of Google’

On May 21, an email announced a runoff election just after 5 p.m.

Sims-Bush’s daughter and Hamilton’s daughter tied. Chromebooks would be dispersed the next day in classrooms – and students would have an hour to vote.

The winner was announced one hour after voting ended.

It wasn’t Sims-Bush’s daughter.

The following morning, Sims-Bush alleged fraud in an official complaint to the school district and requested it look into whether anyone but a student had voted in the election.

“After the runoff election voting window closed, the superintendent published the certified results, naming the daughter of the faculty member, who had unrestricted access to student accounts, and the openly acknowledged bestie of the staffer facilitating the election process the winner,” she wrote in her complaint.

Mississippi Today could not verify whether Hamilton had “unrestricted access.”

Four years prior, a Pensacola, Florida, assistant principal and her daughter were charged with rigging a homecoming queen election. The mother and daughter had access to student emails. A teacher responsible for administering the student election saw that 117 votes were flagged as “false” by Election Runner, an app that runs secure student elections for the district. An investigation followed. The daughter was expelled and charged as an adult after coronation.

Sims-Bush said she found it suspicious that a runoff was called without the vote tally posted.

“As a participant’s parent, I reiterate my request for a review of the May 20th election results,” she added.

Within a week, Sims-Bush had retained counsel and submitted a public records request to inspect the voting records.

She wanted to examine the generated spreadsheet’s time stamps to see if votes were added after the official voting window had closed – and whether each voter was a student in the school by looking at “digital footprint.”

The school district refused.

In the district office’s conference room, between a plea for cooperation on an oral history project and the honoring of a former superintendent, Sims-Bush made her concerns known during the June 10 school board meeting. A video recording of the meeting was posted online by Mic Magazine, a Facebook page that covers locals news in the Mississippi Delta.

More soft-spoken, Sims-Bush, reading from prepared notes, rattled off complaints and spoke to the injustices her family faced.

“It has been horrible. What started as a campaign issue has unraveled so many flawed systems. All types of chaos,” she said. “The goal here is to get official documented results from the school leadership campaign. Dylan Jones made it clear that you pay $1,000 a year for the Cadillac version of Google. We have that recorded. So there shouldn’t be any reason why we shouldn’t be able to see the official results as opposed to something that someone just typed up. ”

She then looked up from her notes to address the board directly. The air conditioning churned.

“Thank you,” said Debra Jones, the school board member for District 3.

The rest of the school board offered no comment.

Two days later, Sims-Bush through attorney Dale Dean filed a lawsuit against Davis, the high school’s principal and Jones to compel them to allow inspection of the “digital footprint” of each voter and time stamps on the generated spreadsheet.

She also wanted $100,000 for “mental anguish,” the cost of filing the claim, loss of economic opportunity, past medical expenses and other enumerated damages.

“I have largely ignored you during this process, as I believe my God-given energy should not be wasted on foolishness,” assistant superintendent William Murphy wrote in his “final” email on the subject.

“This is clearly a sign that the election has gotten you completely outside of yourself.”

‘We are talking about high school students’

Eleven weeks after Hamilton’s daughter was declared the winner, Sims-Bush sat in a mostly empty Greenwood courtroom in the company of friends, family and counsel.

When Circuit Judge Richard A. Smith took his seat, whispers between counsel and client fell to a hush. The school district’s attorney began oral arguments.

“We are talking about high school students,” Mackenzie Price said.

She spoke of the potential for bullying should the metadata or “digital footprint” be made available for Sims-Bush to inspect.

“It would bleed into the hallways,” Price added.

Sims-Bush would have access to the addresses of students if they voted from home and to student names by even glimpsing at the initials listed on the generated spreadsheet. It would be a violation of the Family Education and Right Privilege Act.

The plaintiff wanted to know who her friends’ kids voted for, she interpreted. She was a “disgruntled parent.” Sims-Bush shook her head and looked to her aunt for support.

“The cloud over this matter” is why we’re here today, Dean responded. “All matters of unethical things” and “shenanigans” have taken place. Counsel has submitted “quite voluminous briefs” to “confuse the court.”

He held up case law that had since been overruled as justification for his client’s right to inspect the election metadata. Price noted that case law in asking for a summary judgment for the school district. The judge agreed.

The proceeding was over within an hour.

“Parents now, and I’m guessing going forward, have to rely on the word of people in a district known for fraud, forgery and misconduct when it comes to student elections and other student issues,” Sims-Bush wrote in a comment on Facebook. “It’s sad.”

‘Money can’t buy everything’

She followed her counsel to the hallway outside the courtroom for a huddle. They were discussing strategy and a possible appeal.

“The district adamantly denies any allegations that it was involved in any politics regarding a student election,” said Carlos Palmer, attorney for Sunflower County Consolidated School District. “This particular suit that was filed completely lacked merit and was a waste of district resources that could’ve been better used educating the school’s students.”

The district’s insurance rate could be raised because of the lawsuit, he said.

In the 12 years he has represented school districts, he said he has never come across a lawsuit stemming from a homecoming queen election or any other student personality contest.

Asked to describe personal damages incurred from the alleged theft of the homecoming queen crown, Sims-Bush refused comment on three separate occasions.

On Aug. 17, Greenville Mayor Errick D. Simmons honored Sims-Bush for bringing “regional and national attention to Greenville” and for elevating “the Mississippi Delta as a destination for luxury weddings, sophisticated celebrations and world-class event design.”

When Sims-Bush exited the Leflore County courthouse, she had not let her counsel know whether an appeal would be filed. As of Monday, an appeal has not yet been filed.

“We don’t want student info, we want the truth,” Sims-Bush wrote on Facebook. “What started as a campaign issue is now an issue of moral and ethics.”

“August 20 will be three months and we still have no true results,” she recently posted.

But in town, locals had other ideas about what took place in the Miss Gentry contest in May. Mississippi Today was able to poll half a dozen local residents.

“Money can’t buy everything,” said Tawana, a Popeye’s employee in Indianola and a Gentry alum who wished to be identified by her first name because she has family that attend the school. “Loyalty is something, too. They voted correctly. That’s that situation. You can’t sue nobody for that, neither.”

Gentry High School’s homecoming is Oct. 17.

In conversations with three past Miss Gentry winners, Mississippi Today was able to confirm that the perks of the crown are traditionally limited to appearances at schoolwide events, riding on a float during the homecoming parade and free access to home games. The title carries no cash prize, no scholarship money and no keepsake except the crystal encrusted metal crown bestowed upon the winner. In some years, there is a scepter, too.

One Miss Gentry from 20 years ago theorized that the competition became more fierce and pricey when social media became part of homecoming court election strategy.

“It used to just be about fun,” shared a former Miss Gentry who won her tiara nearly two decades ago. “Parents were not involved. I sang badly to a gospel recording and won because I could make people laugh.”

“It’s still one of the happiest days of my life.”

- Gov. Fordice, from different era, was judged much more harshly than President Trump - March 1, 2026

- ‘We can only go up from here’: Hope and apathy in Wilkinson County schools - February 28, 2026

- Community discussion grows around 24-hour child care in Hattiesburg - February 28, 2026