FOREST – Cheryl Baier pushed her car key into the ignition when her boyfriend approached her passenger window in a Walmart parking lot in Forest. Bilbo Faulkner then pushed the passenger door open, sat down beside her and began to punch.

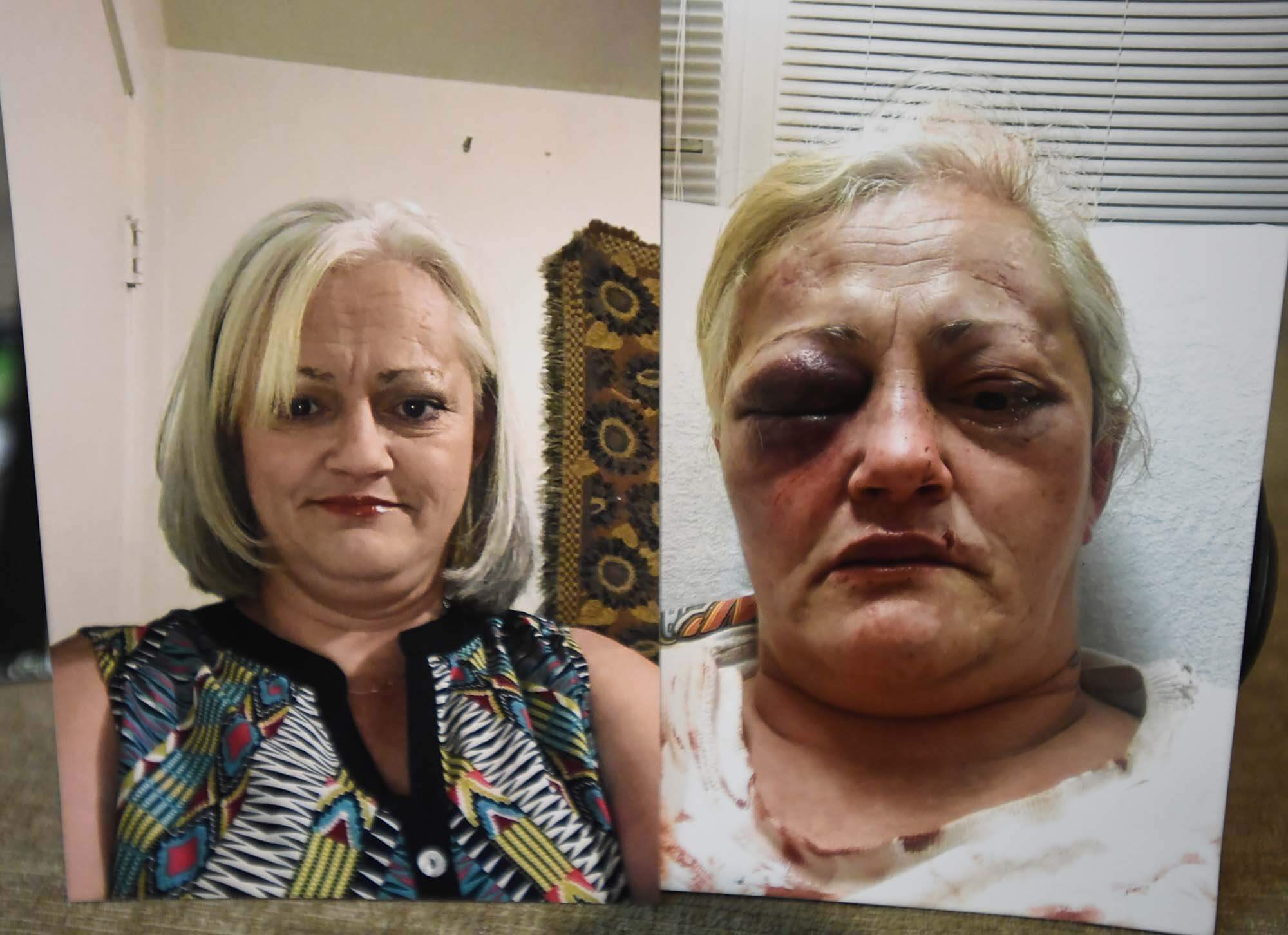

Baier saw red and black. Blood dripped from where her vision grew blurry. She screamed but only choked. He pried the car keys from her grasp and strangled her with her seatbelt. She cried for help as he hit. She reached for the horn. No honk. She felt one of her eyes come loose after what seemed like 20 blows.

“I was hoping he’d just knock me out and put me out of my misery. So I didn’t feel it no more,” Baier remembers.

It was dark outside at 9 p.m. The car was parked yards from the main entrance underneath a lamp. She had agreed to meet her boyfriend in the lot because it was a public space. Few shoppers stopped to see his fist against her face or hear her cries, though. She saw a couple pull their child away before she lost vision in her right eye. That’s when she says Faulkner threatened to burn down her house before speeding off in his car. A witness eventually called the police, who instructed the fire department to rush to her home.

When she arrived at the hospital, she wasn’t sure if she was alive.

Victimized by crime, Baier later found herself victimized by a justice system that denied her critical aid because she had a more than decade-old drug conviction, even while the system gave her abuser one of the lightest sentences possible for an attack that left her temporarily homeless and with failing sight. Even though Mississippi has long boasted long sentences and high incarceration rates, domestic abuse cases still rarely rise to felony status – and offenders in those cases receive lighter sentences than other protected classes.

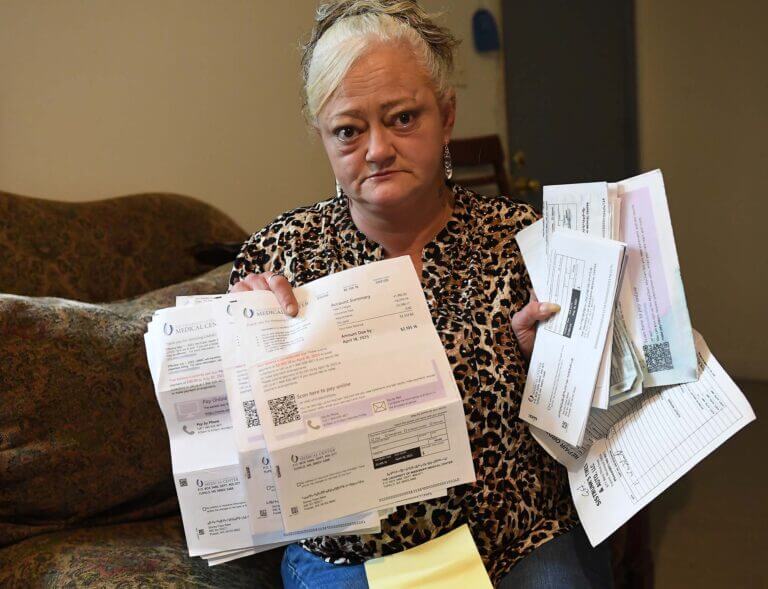

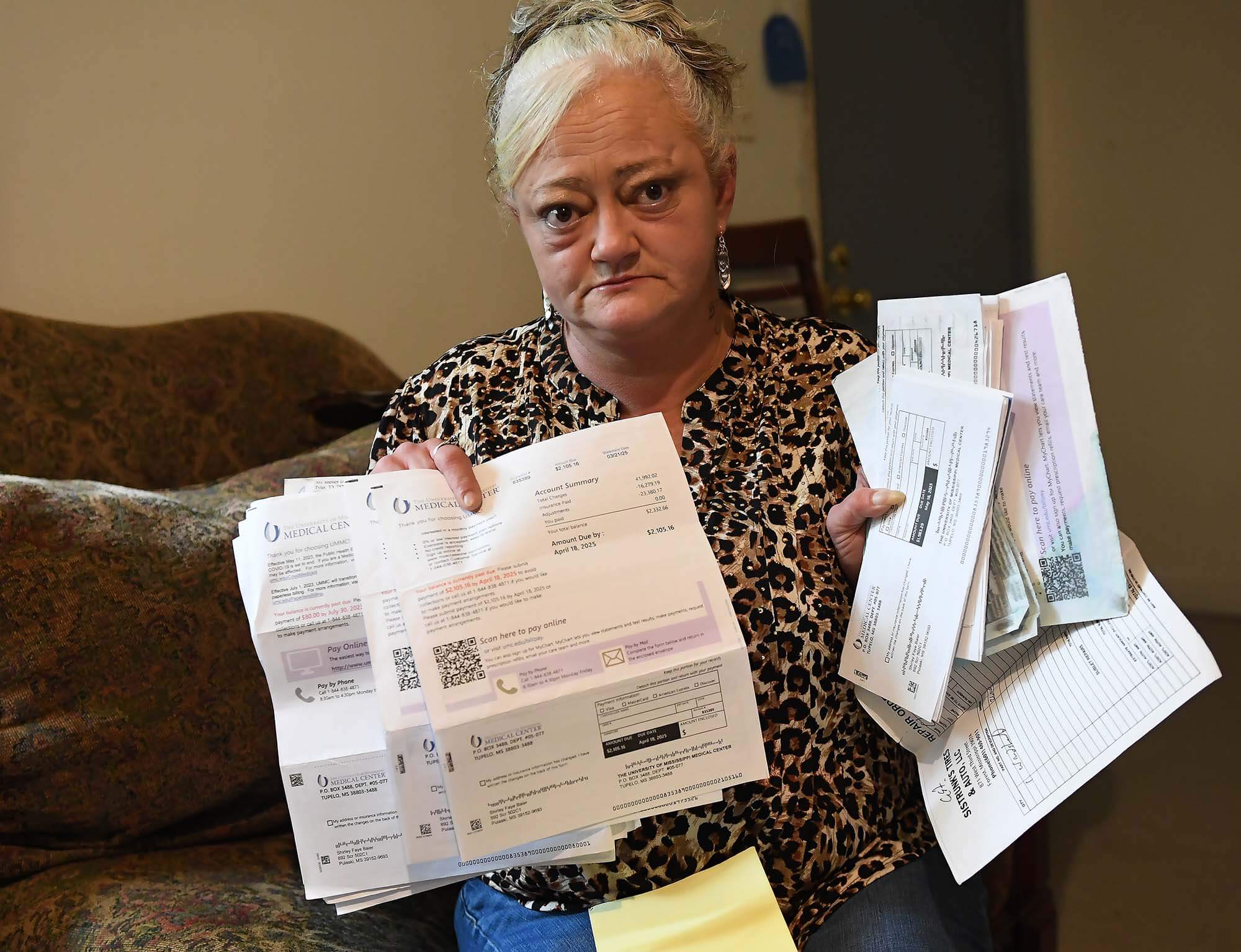

Unable to cover the over $12,000 in medical bills, Baier, a convenience store clerk, filed a claim for crime victims’ compensation through the attorney general’s office. The maximum payout to cover medical bills is $15,000. After her night stay at the hospital and 10 days of recovery, she was able to return to work. Paid $10 per hour at 45 hours a week, she knew it’d be several years before she could pay off her medical debt.

Weeks out from her surgery, she pulled a letter from the mailbox and squinted to make out the writing. The attorney general’s office denied her claim because of her felony drug conviction from 13 years ago. Victims, she learned, must be five years out from the last day of their probation to qualify for the program. Baier was weeks away.

“My pain is just the same. My loss is just the same,” Baier said in an interview with Mississippi Today. “What happened to me had nothing to do with what I did over a decade ago.”

While five other states deny victims’ compensation for prior felony convictions, Mississippi and Louisiana count all felonies, including victimless and nonviolent ones. Mississippi is also unique in counting probation, post-release supervision and court-ordered drug treatments, among other programs sponsored by the Department of Corrections, as part of their incarceration time.

Nearly a quarter of denied applications between 2021 and 2023 were based on prior felony convictions. The amount the AG’s office paid out to cover medical costs for assaulted crime victims decreased by half each year from 2021 to 2023, from a total of $1,424,475 in 2021 to $534,026 in 2023.

“The rules can unintentionally create barriers, and we must stay mindful of the fund’s original purpose,” said Stacey Riley, who provides shelter to 25 children and 30 adults through the Gulf Coast Center for Nonviolence in Biloxi. “Administrators should approach this work with an understanding of survivors’ trauma, their specific needs, and the often challenging environments in which they live.”

Some justice

In the months after her assault and the arson at her home, Baier lived out of a camper parked in her front yard. She wore a purse around her neck with a deer-skinning knife inside. Some nights she wet herself, too afraid to push open the RV door and use the restroom in her burnt home. She stayed up most nights with a pain in her mouth and eyes, unable to rest after working double shifts at the convenience store.

She lived for her day in court when restitution would be set and she could deliver her statement. She wrote out the facts on a piece of loose-leaf paper for the judge, jury and court officers to hear. She had June 2 marked on the calendar on her phone and in her kitchen. She called the district attorney’s office and the victim service coordinator each week, checking to make sure she had the date of the hearing correct.

She missed 15 days of work for court, many of them earlier trial dates that were bumped. She missed close to a month from surgery that eased her right eye back into its socket. In total, she estimates that she lost about $5,800 in wages.

When the hearing date arrived, Baier waited in a room in the courthouse with a printout of her victim impact statement. She was told to come back the next day when Faulkner would only plead. Restitution was set the next day, too. The victim service coordinator promised to let her know when she’d get a chance to tell her story in court and impress upon the judge the need for a substantial restitution payment. Baier waited for hours.

During the hearing, District Attorney Chris Posey remarked, “This does come with the approval of the victim in this case who I’ve spoken with many times and believe is actually in the courthouse today although not in the room at the moment.” But Baier said Posey never spoke to her about the plea deal.

The Victims’ Bill of Rights entitles victims to be present for all hearings before a judge. Baier wasn’t present to dispute the characterization of the attack she experienced. Posey attributed the attack to “some type of argument” between Faulkner and Baier.

Faulkner pleaded guilty to three years for aggravated domestic violence with time served for the 767 days spent in the Scott County jail for assaulting a jail guard. Restitution was set at $14,000 shy of the amount Baier asked for. She would get $2,000 at the end of the month – with the rest paid in $150 monthly installments once Faulkner’s court fines and fees were paid. The clerk then let her know she could leave.

Faulkner was also assigned an anger management course that he already took for a prior assault.

In an interview with Mississippi Today, Posey said that because the hearing took place in the courthouse while jury selection was happening for a separate trial, it would’ve been impossible for Baier to give her statement. The hearing was in the judge’s chambers, not the courtroom.

The victim service coordinator in the case refused a request for comment by Mississippi Today.

“What was said was further from the truth because that just makes it seem like he’s responding instead of the psychopathic behavior it truly was,” Baier said. “There was no foundation.”

Six percent of domestic violence cases were prosecuted as felony domestic aggravated assault in 2024, according to data from the Mississippi Administrative Office of Courts compiled by the Center for Violence Prevention.

“Too often, the gravity of domestic violence is misunderstood,” Riley said. “These are not simply individuals who ‘can’t get along’ with their partners — they are perpetrators of violence, many of whom will go on to commit even more serious crimes.”

On the street where she lives

Baier was pulling out of her driveway in Pulaski in Smith County when she saw a familiar face picking up a neighbor’s trash bin – and dumping the contents into the compactor. It was Faulkner. He was wearing the county jail striped orange pants. They locked eyes as she passed him on the gravel road by her house.

“There was no guard,” Baier said. “The way he beat me in the Walmart parking lot in front of God and everybody – you think he would hesitate in front of that trucker or another inmate?”

Mississippi Today was able to confirm that Faulkner, convicted of aggravated domestic violence along with two other prior violent felonies, was made a trusty at the Smith County jail — and was on work detail as a garbage collector on her street.

When Mississippi Today brought this to the Smith County Sheriff’s Department’s attention, the sheriff relayed that Faulkner was no longer in the program. He didn’t know Faulkner had been convicted, he was only going off the man’s criminal record in his county.

Mississippi Department of Corrections policies prohibit inmates convicted of violent felonies, including aggravated domestic violence, from serving as trusties.

“Much of the problem comes down to communication,” said Riley, whose organization operates in 24 municipal justice courts in the lower six counties in Mississippi. “The issue isn’t that our justice system fails to act — it’s that it has long operated in silos. This entrenched way of functioning must change if we are to respond more effectively to interpersonal violence.”

In 2022, Attorney General Lynn Fitch established the Mississippi Domestic Violence Registry, which gives law enforcement access to information helpful for keeping law enforcement, victims and bystanders safe when answering domestic violence calls. It has been “a little slow” to get cooperation from agencies, said Michelle Williams, a spokesperson for the attorney general’s office, as officers have a lot of competing paperwork requirements. In an attempt to reduce this, Fitch’s office incorporated the registry into existing law enforcement reporting platforms.

Luke Thompson, former Byram police chief, said it was hard to convince his deputies to investigate domestic violence cases. He advocated for the attorney general’s office’s registry to be incorporated into the National Incident Based Reporting System, administered by the FBI.

Domestic violence cases require dual reporting and more paperwork than other cases. Officers are expected to determine a primary aggressor, which requires more discretion. Since 1992, just over a third of shootings of officers happened during domestic violence calls, Thompson found in his agency’s data.

Since retiring as chief, Thompson has been helping Mississippi agencies implement the Lethality Assessment Program, a questionnaire that helps law enforcement identify victims and serial abusers in their communities. The program helped his department connect victims with services faster and provide prosecutors with a more thorough history of abuse.

“It’s one of the hardest types of cases to sort through,” Thompson said. “Cops focus on ‘bad guys.’ We’re empathetic to victims. But sometimes we don’t always take that extra step to get a victim’s help.”

‘There was nothing in his eyes’

While the father of Baier’s children was incarcerated, he had sent Faulkner to be her protector. She felt taken care of by Faulkner, with his wide back and a muscular frame. She remembers the first day he arrived at the convenience store where she worked. She was drawn to the kindness he showed to another single mother. He provided money to her when she fell behind on car payments.

They were friends before they began dating. She enjoyed going on evening drives listening to “Good Ol’ Girl” by Frank Foster around Smith County when they were both off work. She knew he had been to prison, was first put off by his many tattoos, but was taken by his “big heart.”

For one month, he had been living with Baier, who was surprised when he announced he would be moving out. He had recently begun accusing her of cheating, which she thought was a joke. A relative of Faulkner’s attributes his behavior to untreated bipolar disorder. Baier said that he had been drinking alcohol.

Before that day at Walmart, when he assaulted her, Baier had never seen his violent side. He asked to meet up while she was still working at the convenience store that night. She chose a public space because “there was nothing in his eyes.” He just looked different, she said.

“It was premeditated,” Baier said, clutching a charred family photo in her Smith County home. “That’s part of what’s gotten me all this time.”

Although she was able to clean her house, the smell of smoke persists. The fire damaged a photograph of four generations of her family. It was the last picture she had with her grandfather before he died from cancer.

Baier is well known in her community. She meets most locals as a clerk at a popular store in Forest where checks are cashed. She knows the farmhands who buy equipment and the waitresses at the local restaurants. Young and old, from out of town and native, they all chat with her at the store.

Lately, she’s been acting as her own investigator. She collected a list of witnesses from her assault as well as to the arson to hand to authorities. She helped the boss at her place of work transfer security footage onto a flash drive to capture the moment Faulkner entered the convenience store earlier in the night of her assault when he allegedly bought alcohol. The arson at her home has not gone to trial. No witnesses have been interviewed.

Her first eye surgery wasn’t considered a success because the muscles and tissues were damaged, pushing her right eye forward and causing pressure and migraines.

In a handwritten letter to the crime victim compensation director, Baier wrote, “After the fire, all I had was the torn, blood stained clothes on my back. My home was not habitable for four months. I’m telling you all this so you can understand the great financial strain, not to mention the physical and emotional damage that I will probably always suffer.”

Over half of completed victim compensation claims were denied in Scott County between 2021 and 2023, according to records obtained by Mississippi Today. Thirteen were denied and 11 were approved with an award.

“When I got your denial and read the explanation, I felt abused and victimized all over again in a different way but just as damaging. Does a mistake from 13 years ago make me any less of a victim? Does it make what happened to me any less painful? Did it make me deserve what he did to me?”