Editor’s note: This article contains a photo that some readers may find disturbing.

On an August afternoon in 2023, three inmates at the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility evaded the notice of guards and slipped away from their housing unit.

They weren’t plotting to escape the Rankin County prison. Instead, they were on a rescue mission. On their shoulders, they carried a man whose legs seemed to be rotting from the inside out, his flesh cracking like leather left to shrivel in the sun.

The prisoners decided to take matters into their own hands. They headed for the office of corrections officials to find help and, without a guard stationed on the facility’s watchtower, made their way across the grounds.

When they reached the outside of a multipurpose building, they spotted Stephanie Nowlin and shouted her name.

“Think of it like a scarecrow, almost,” Nowlin said, recounting the episode in an interview with Mississippi Today. “It’s how they were carrying him, one on either side, and his arms were just off their shoulders.”

The image embedded itself in Nowlin’s mind, but it was only one moment among many that charted her course from high-ranking prison official to public critic of the system she once served.

Behind Bars, Beyond Care:

A Mississippi Today investigation into suffering, secrecy and the business of prison health care

For almost two years, Nowlin was one of Mississippi Department of Corrections Commissioner Burl Cain’s top lieutenants. Cain hired Nowlin after she had served time in prison herself and made her his government affairs coordinator. The pair developed such a close bond that she came to view him like a grandfather. Now, she is speaking out about what she said is widespread medical neglect and mismanagement inside the agency and its facilities.

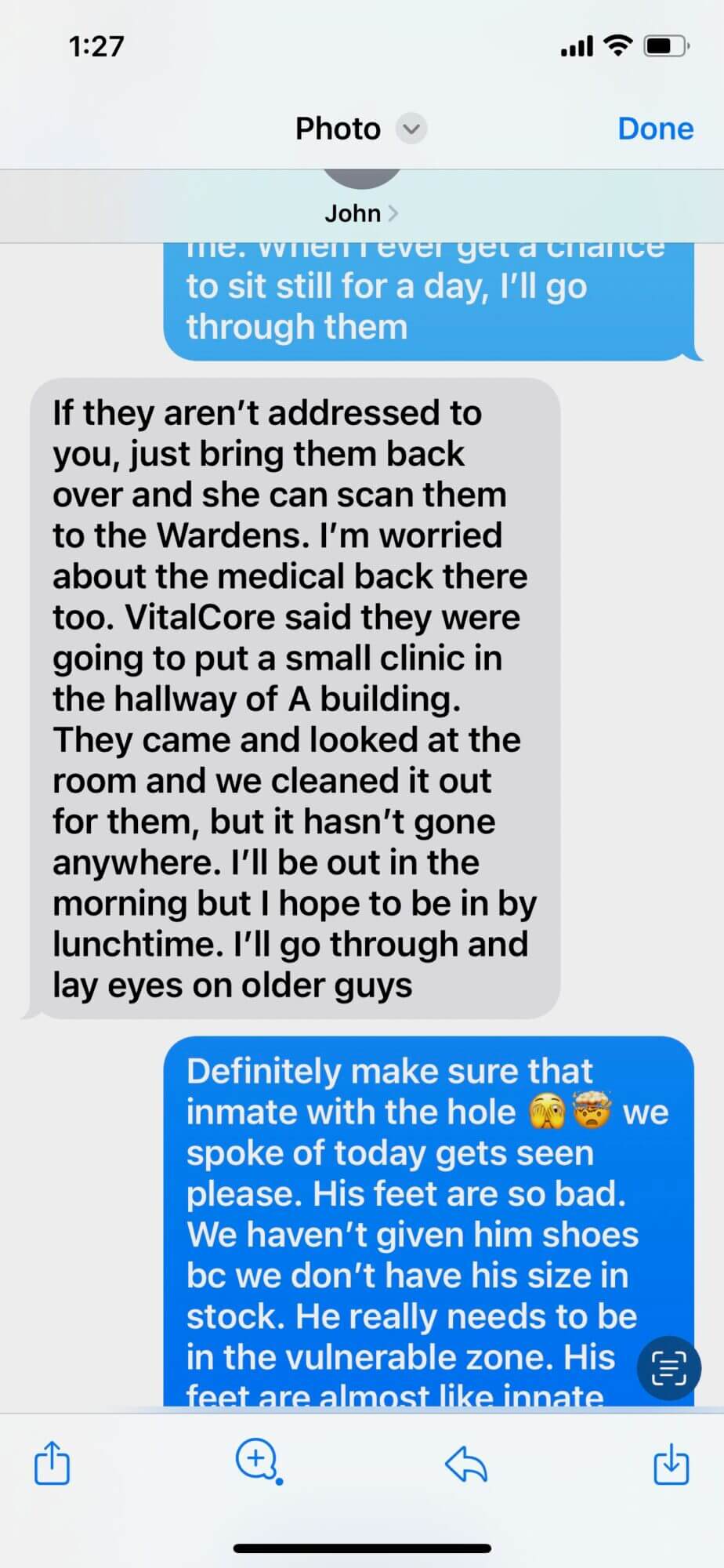

Nowlin provided Mississippi Today with internal messages between current and former department officials showing officials criticizing VitalCore Health Strategies, the company contracted to provide medical care to Mississippi prisoners. The messages show that in private, officials lamented the quality of VitalCore’s health care services even as the company raked in hundreds of millions in public dollars — a money pot that has been growing larger for years.

Nowlin came forward after Mississippi Today reported on the House Corrections chairwoman’s allegations that MDOC is running a financial deficit for its medical program at the same time sick prisoners languish without proper care.

In response to Mississippi Today’s questions for that article, MDOC spokesperson Kate Head said the conditions inside Mississippi prisons exceed “constitutional standards” and denied any allegation that inmates receive care below such standards.

The statement compelled Nowlin to reveal what she said she and other prison officials have seen — neglect and mismanagement that contradicts MDOC’s claims that it provides inmates with proper medical care.

“It affected me tremendously. I could not sleep,” Nowlin said of the statement. “There are just so many things that are wrong with that.”

In a statement, Head did not respond to a detailed list of questions about the specific episode Nowlin mentioned, the internal communications obtained by Mississippi Today or the department’s provision of health care.

READ MORE: Behind Bars, Beyond Care: A Mississippi Today investigation

“The Mississippi Department of Corrections is restricted by federal law from disclosing or commenting on the medical condition and/or treatment of the inmate population,” Head wrote.

A VitalCore spokesperson did not respond to multiple emails and phone calls requesting comment. The company has previously said it provides “comprehensive and competent” health care services to Mississippi inmates.

Nowlin has filed state and federal lawsuits against MDOC related to a personal matter involving her former parole officer — a matter that predated her work at the department.

In interviews, Nowlin pointed to systemic problems, such as a backlogged and dysfunctional system for getting inmates critical medical services and assigning them to housing units.

The result, Nowlin said, is that sick inmates get lost in the correctional system — behind bars, beyond care.

“There are major damages being done. Not just to tax dollars but to real humans. People just like me who made mistakes and who shouldn’t suffer at the hands of egos, politics, laziness, hypocrites and more,” Nowlin said. “I’m ashamed of this system.”

From prisoner to prison official

Nowlin had first been inside the walls of the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility as a prisoner. She was incarcerated between January 2017 and July 2019 for aggravated DUI and served part of her sentence at CMCF.

After her release, Nowlin worked as an events director for a hotel. Outside of work, she attended church services and began sharing her perspective as a former inmate on how the state could better rehabilitate the people inside its prisons. One woman she met at church was a friend of Cain and, following a recommendation, Nowlin got in touch with him.

The two spoke for hours over the phone, and following an in-person meeting, Cain invited her to accompany him on a trip to the Angola State Prison in Louisiana, where he had been the warden. The pair attended Angola’s prison rodeo, a program Cain created that attracted national attention for the spectacle of events like bull riding and “convict poker.”

Cain touted the rodeo as a way to generate revenue for prisons and drive “moral rehabilitation” among inmates – an approach that often saw Cain push to incorporate religious teachings into prison programs.

Nowlin said she was hesitant to work in a system whose shortcomings she experienced firsthand, but Nowlin was swayed by the affection with which Cain interacted with inmates: “When I saw it firsthand, you see these people in the striped jumpsuits like I was and the way he treated these humans, I can’t even put it into words. I wanted to be a part of that.”

In the fall of 2022, she accepted a job as MDOC’s government affairs coordinator, a position that tasked her with supporting the agency’s interests at the Capitol and working onsite at prisons to develop reforms.

“Five years ago I was on much different grounds with MDOC. I am here to tell you, do not give up or lose hope,” Nowlin wrote in a Facebook post announcing her new job. “I’m so honored to be a part of Mr. Burl Cain’s team. Seeing the way these men respect him and what he has done for the forgotten inspired me more than I honestly think I have ever seen. I’m thankful and ready for the opportunity that I have been blessed with.”

Nowlin began working to alleviate what she said was a lengthy backlog for reclassification, the processes for updating an inmate’s custody level throughout their incarceration. Reclassification is supposed to ensure inmates are placed in the least restrictive environment possible while maintaining prison security. But Nowlin said MDOC didn’t employ enough case workers, and inmates would frequently get stuck in restrictive housing assignments for far longer than necessary.

That is what made CMCF a central focus of her work, and it is what brought her to the prison on Aug. 17, 2023.

‘He’s fine and noncompliant’

Nowlin said she had been tapped as a potential replacement for Cathy Fontenot, who worked as a consultant for MDOC, focusing in part on inmate classification and reclassification.

Fontenot previously worked under Cain at Angola as an assistant warden, and for a time handled public relations. Some credit Fontenot with helping to cultivate “the legend of Cain,” a narrative which casts Cain as a near-miracle worker who curbed the violence at what had been one of the South’s bloodiest prisons.

Fontenot is among a cohort of allies who followed Cain to MDOC after he resigned from his post at Angola in 2015 following allegations that he misused public funds. Cain denied wrongdoing and was never charged with a crime.

Nowlin began working with a team of case workers to help manage the department’s backlogged inmate reclassification system — a task she found intractable.

On that August day in 2023, Nowlin had been trudging through inmate reclassifications when she stepped outside to take a call. That is when, to her horror, she encountered the inmates carrying the man whose leg flesh appeared to be rotting. Mississippi Today is declining to publish the man’s name to protect his medical privacy.

The man’s fellow inmates carried him from “quickbed” — a unit for newly arrived inmates undergoing initial classification. It is comprised of inmate “zones” where inmates sleep on bunk beds in dormitory-style housing.

After seeing the man’s legs, Nowlin took photos and she called John Hunt, then the superintendent of CMCF, who has since become the corrections department’s deputy commissioner of institutions.

Hunt arrived, and he and Nowlin transported the sick inmate to the prison infirmary on a golf cart.

Once at the infirmary, Nowlin said, nurses declared the man “noncompliant” because he allegedly had not been taking his diabetes medication. The next day, Nowlin went to check on him and saw that medical staff had rubbed some sort of ointment on his leg and sent him back to his zone.

“That’s all they did,” Nowlin said. “They didn’t send him to the hospital. They didn’t do anything other than that.”

Nowlin also texted the photos to Jay Mallet, then MDOC’s deputy commissioner of institutions. Mallet, after seeing the man’s legs, said prison medical staff frequently declare sick prisoners “noncompliant” and send them back to their cells.

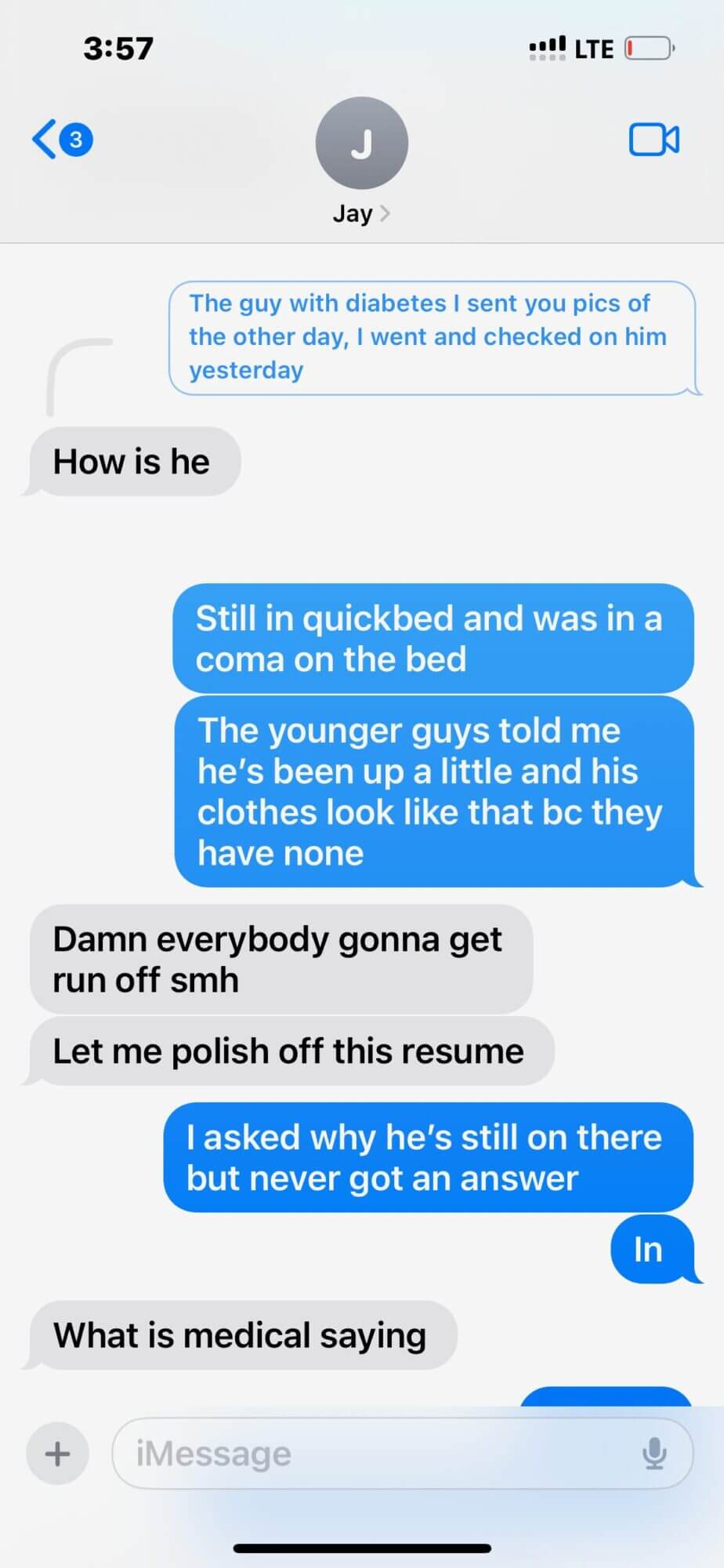

A transcript of texts about the inmate reads:

Mallet: Wait is that real

Mallet: What is that and how long has it been like that

Nowlin: Yes Jay! It’s his legs

Nowlin: I don’t know how long it’s been like that. The nurses keep trying to say he’s noncompliant with his meds, etc. they were going to just send him back. Hunt and I just drove him over on a cart and are having quickbed nurses clean him up. I don’t have any authority to ask any other questions but it’s so fking bad

Mallet: That is what medical does a lot of

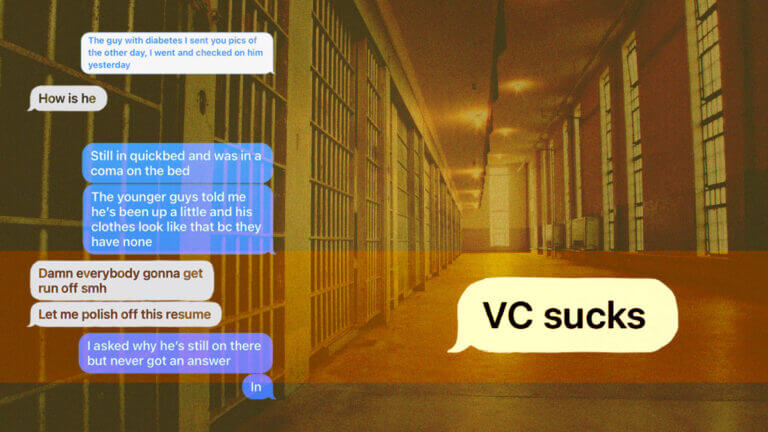

Over the next few days, the pair engaged in another text exchange about the incident where Mallet, who was a member of MDOC’s executive leadership and one of the highest-ranking officials in the department, said VitalCore, which he referred to as VC, “sucks” – a statement he made the same year the state agreed to pay VitalCore about $100 million in taxpayer funds.

Nowlin: I honestly have no idea if they even cleaned up his legs

Mallet: VC sucks

Mallet also criticized medical staff for allegedly saying the man’s dire condition was partially due to his diet.

Mallet: What is medical saying

Nowlin: Pshhhh he’s fine and noncompliant … Bc he won’t eat right, like are you fking kidding me…

Mallet: What the hell is eating other than what’s served

Nowlin: Exactly. The main clinic was just about to send him back. Jay he couldn’t hold his eyes open

When discussing the man’s condition when he had allegedly fallen into a coma, Mallet also seemed to suggest people would lose their jobs.

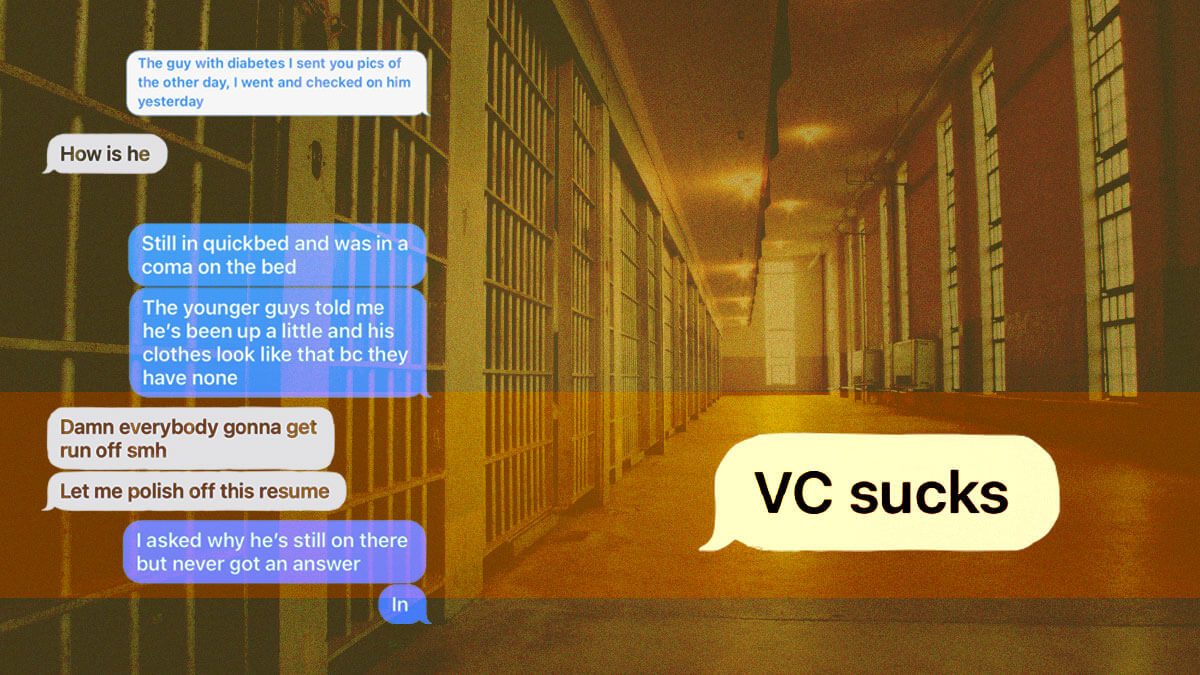

Mallet: How is he

Nowlin: Still in quickbed and was in a coma on the bed

Mallet: Damn everybody gonna get run off smh

Mallet: Let me polish off this resume

Mallet did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Nowlin was not able to confirm what happened to the inmate. Prison records do not show a man who meets his description as currently incarcerated, and parole records don’t show someone with his name as having been released over the past two years.

In interviews, Nowlin said the episode was not a gruesome exception to the routine process for evaluating and treating sick inmates in Mississippi’s prisons, but emblematic of a systemic problem.

The backlog

The sprawling CMCF was built on 171 acres in Pearl in Rankin County. It can house a little over 4,100 offenders, according to the corrections department. The prison is the first stop for people sentenced to serve time in Mississippi, and as such, conducts initial orientation and classification.

Inmates are classified and assigned to facilities based on a variety of factors, including “level of care designations,” which refer to their health care needs. MDOC says inmates are placed based on their needs and the space and security needs of the department, but the department doesn’t follow its own policies, Nowlin said.

Inmates are supposed to get reclassified on a continuing basis in order to evaluate their condition and behavior, but there aren’t enough case managers to stay on top of the process. As a result, inmates often get stuck in restrictive housing or in facilities that can’t accommodate their health care needs, Nowlin said.

As the classification backlog grew and the medical ailments of many inmates went untreated, VitalCore failed to keep its promises to expand prison health care services, text messages obtained by Mississippi Today allege.

Hunt, the current deputy commissioner of institutions, texted Nowlin that he was concerned about the care VitalCore was providing and said they promised to build a medical clinic in one of the prison buildings at CMCF, but never did.

“I’m worried about the medical back there too,” Hunt wrote. “VitalCore said they were going to put a small clinic in the hallway of A Building. They came and looked at the room and we cleaned it out for them, but it hasn’t gone anywhere.”

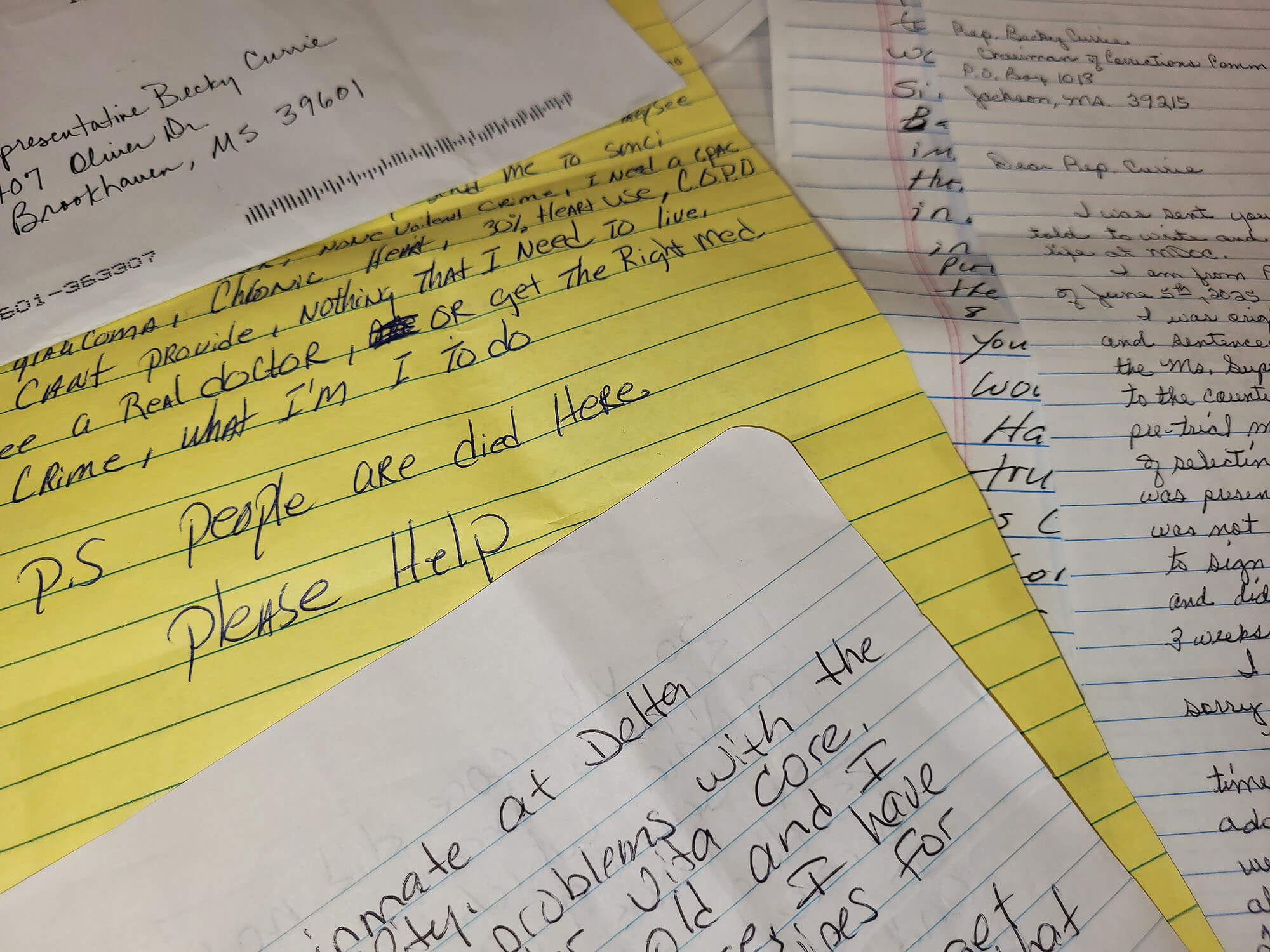

In the next fiscal year, Mississippi is set to spend over $121 million on prison medical services, a number that has been climbing for years. Republican Rep. Becky Currie, the House Corrections chairwoman responsible for conducting oversight of MDOC’s budget, said there is little evidence that the money is being spent on providing quality care.

VitalCore officials “do nothing but pull these fat salaries from the contract and do absolutely nothing for the inmates,” Nowlin said.

More than one person at the top

Nowlin left MDOC in May of 2024 and now works as a legal administrative assistant at a law firm.

Cain, who plucked her from obscurity and elevated her to a powerful position helping to manage the system under which she was once jailed, is overseeing some problems that predated his tenure, Nowlin believes. The problems, she added, are system-wide.

“He disappointed me tremendously, but I think he wanted to clear his name from Angola and come over here,” she said.

“The way that this system is set up in the state of Mississippi, when you’ve got 20,000 inmates spread out all around, all of this corruption. It’s almost set up for anyone to fail, unless these legislators, along with many others, wake up and get on board and realize that it’s more than just one person at the top.”

One legislator, Currie, embarked on several tours inside Mississippi’s prisons. Once inside the grounds of these facilities, the lawmaker says she witnessed widespread suffering — suffering she believes is preventable.

Currie said she saw Hepatitis C and HIV patients denied lifesaving medication. She saw diabetics go untreated and cancer patients dying from lack of care. These are human costs, she said, of a state prison system where silence and secrecy conceal suffering: “It’s a kingdom, and they do not want you looking in.”