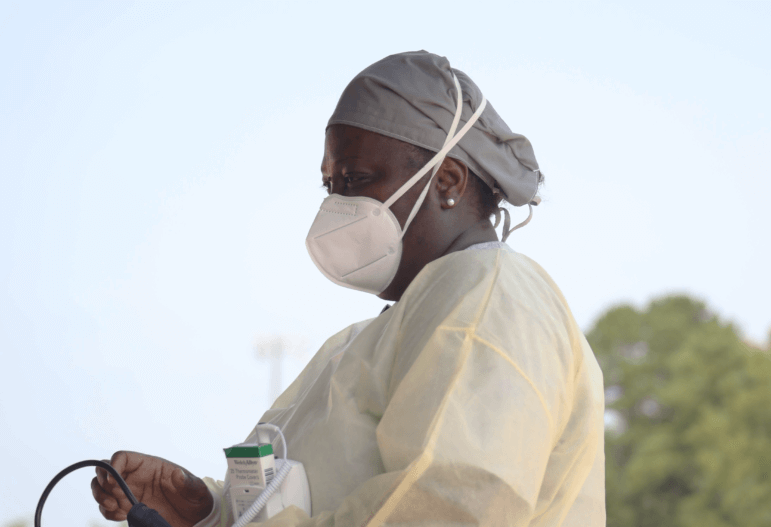

Eric J. Shelton/Mississippi Today

Daphne Webster-Quinn enters data into her computer at a COVID-19 testing site in Lexington, Miss., Thursday, April 30, 2020.

‘Forced to fight a war on two fronts’: How healthcare workers say misinformation and messaging worsen the toll COVID takes in Mississippi

Healthcare workers in Mississippi are twice as likely to contract the virus compared to the general public, totaling more than 5,300 cases to date. Many say in addition to staff cuts, PPE shortages and growing fatigue, they’re battling misinformation as they try to do their jobs.

By Erica Hensley | September 21, 2020

HOLMES COUNTY — Daphne Webster-Quinn says a prayer before every shift to ask for protection for herself and coworkers, and healing for her patients. Donning full personal protective equipment, three days a week she works a primary care clinic on wheels, crisscrossing rural Holmes County to meet patients where they are.

As a medical assistant for Mallory Community Health Center, she splits her time between the clinic in Lexington and a mobile unit that dispatches across every corner of the county to offer free COVID-19 tests and primary care check-ups to a community that’s been devastated by coronavirus. The majority-Black county has seen the highest number of cases per capita for most of the pandemic, currently double the rate of the state.

Webster-Quinn herself contracted the virus in July and had to take off work for a month while she recovered. She is one of the over 5,300 healthcare workers who have contracted the coronavirus in Mississippi since the pandemic hit the state six months ago. At least 32 have died, according to limited data obtained from the Mississippi State Department of Health through a public records request.

Healthcare workers have publicly lamented personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages, staff cuts, and the emotional and physical toll taken across Mississippi during the pandemic. A half-year in, as the number of daily cases start to improve after a long summer peak, the heightened sense of anxiety and worry — navigated through bouts of highs and lows, adrenaline and fatigue — have worn into a chronic state of stress. Too, many say they’re constantly battling misinformation in the community, fueled by conflicting messages from federal and state leadership.

Webster-Quinn’s teenage daughter caught it at the same time and they quarantined together in her bedroom, cut off from their family. Her mom came to her window to pray over them. Her husband bought a dorm fridge and stocked them up with liquids and snacks. Her son contracted the virus a week later.

“My husband couldn’t hug me to tell me it’s alright and my kids were crying because they want healing for their parents,” she said. She wants everyone to realize, “It’s not if it’s going to knock on your front door, it’s when it’s coming to knock on your front door.”

The virus was terrifying because of her symptoms and, like almost every healthcare worker Mississippi Today talked to for this story, she has family or colleagues who’ve died from it. But adding insult to injury says Webster-Quinn, is the people who still don’t take it seriously.

Both Webster-Quinn and her daughter’s cases were bad — it was like someone was standing on her chest, she says. She’s known six people to die from COVID-19 and while worried for her own life, she prioritized caring for her daughter. Even in quarantine while distracting herself with caring for her daughter, she couldn’t quiet the anxiety over people who still go maskless or flout distancing and testing guidelines, such as waiting for your result before socializing.

Recalling rubbing her daughter down with ointment, “I was just watching the rise and fall of her chest every night. But you got people out here not taking it seriously, and I have a serious problem with that.”

Most hospitals’ number of COVID-19 patients is decreasing, but other factors like reduced staff, increased levels of delayed primary care and ongoing squeeze on the highest trauma centers keep healthcare workers at prolonged full-speed. For the state’s healthcare system, there is no off switch and the curve has yet to flatten.

The health department says the 5,300 healthcare worker case data are incomplete, likely under-counting the actual number. There are about 126,000 healthcare workers across Mississippi actively working in or around clinics, according to federal tracking. Cases are usually only counted as healthcare workers if they’re investigated.

Across the state, contact tracers have struggled to keep up with demand, not able to reach cases to collect transmission and demographic information or issue quarantine orders. As of early September, the state health department had only investigated 68% of all cases, according to documents obtained by Mississippi Today, though 100 more investigators are on the way to help reach more cases. State contact tracers closed 87% of case investigations in mid-July, as state health officer Thomas Dobbs warned the summer surge in cases was quickly outpacing their ability to keep up.

Research shows healthcare workers are at least three times more likely to contract coronavirus compared to the general public, further suggesting Mississippi isn’t adequately tracking cases among frontline health workers, despite the state’s foremost goal of protecting healthcare workers and the medical system. As of early September, Mississippi had 425 cases for every 10,000 healthcare workers, compared to 294 in the general public.

The Mississippi Delta has been hit hard by COVID-19, with every county seeing at least 400 cases for every 10,000 residents, compared to the state average of around 300 cases per capita. Holmes County sees the highest rate of community cases in the state.

An hour north in Greenwood, every time Dr. Rachael Faught takes a dinner break to meet her family at home, the second she walks through the door her young sons ask, “Are you here for forever?” Usually, the answer is no. She runs home in between rushes at the nearby hospital where she’s on call 24-hours a day for seven-day shifts. As one of Greenwood-Leflore Hospital’s two pulmonologists, together with the respiratory therapists and nurses, she treats lung conditions.

If medical assistant Webster-Quinn is the first line of defense, Faught is the last. In theory, the more Webster-Quinn and other preventive care providers are able to test and isolate, and make sure people are healthy in case they do contract the virus, the fewer patients Faught will treat on a ventilator. They both wear full PPE — gloves, gowns, N95 masks and shields — as they offer frontline COVID-19 care to Delta residents, and both say the pandemic has taken an unexpected toll at work and at home.

Though the novel coronavirus has been shown to affect other organs, lungs are the most restricted. Faught and her team use mechanical ventilators to artificially breathe for patients whose lungs cannot pump enough air to sustain life alone. Siloed into COVID-19 wards, patients with the coronavirus — no matter the severity of their case — all stay on the second floor of the hospital, to isolate spread across other units. Faught watches carefully for shortness of breath and low levels of oxygen — signs a case is worsening and a ventilator might be needed to breathe for the patient. But with the heightened vigilance comes unknowns.

“That’s the one thing about this, is that when people start to go bad, they usually go back very quickly and even with months of experience, we can’t always predict who’s going to get worse,” Faught said. “But with these COVID patients it’s almost always an issue with oxygen.”

And once these patients are on ventilated breathing, they stay there for weeks, she says, compared to most conditions that only take a few days to treat.

Greenwood-Leflore’s COVID-19 ward hasn’t seen the same steep reduction that many across the state have, Faught says, though numbers have slightly declined over September and remain steady. The Delta has the fewest COVID-19 medical centers, with only three hospitals providing Level 3 or higher care.

COVID-19 care in Mississippi relies on a “systems of care” model that designates each hospital at a certain level based on their expertise and resources — designed with the state’s trauma system in mind — to reduce timely and expensive, and potentially fatal, transfers to unequipped hospitals. Only one hospital, Delta Regional Medical Center in Greenville, offers Level 2 COVID care in the region. University of Mississippi Medical Center is the only Level 1 in the state for COVID and trauma, offering the highest level of care.

In Tupelo, Dr. Josh Calcote says the stress is felt in a different way — through auxiliary care the Level 2 trauma center is offering to buttress lacking trauma capacities across the region. The hospital is still treating COVID-19 patients, but it’s the increase in general acute and trauma care that has stressed the system, he says. UMMC’s intensive care unit stays full and when they can’t accept additional patients, trauma care is usually outsourced to Alabama, Louisiana or Tennessee. If they’re full, as has been the case, Level 2 trauma centers like Calcote’s North Mississippi Medical Center, Forrest General or Gulfport Memorial have to meet trauma needs.

“The analogy I would use, with some of these advanced surgeries is it’s like if you took some kind of military fighter jet to an auto mechanic and said, ‘Hey, fix this, it’s broken.’,” he said.

Though COVID-19 hospitalizations across the state are improving, the healthcare system is still stretched thinner than normal. As of Thursday, 81% of ICU beds across the state were full, compared to a baseline of 66% in 2018. Combined, the state’s four highest level trauma centers’ ICUs are 93% full, according to state tracking.

In midst of soaking up overflow higher-need trauma treatment from other trauma centers, Calcote, a hospitalist, is bracing for flu season as he treats higher need patients across the board. During March and April, most hospitals’ daily patient census plummeted, and with it, revenue.

Not only were elective surgeries paused to preserve PPE and resources, but primary and preventive care patients — especially those with compromised immune systems and higher-risk for coronavirus complications — were hesitant to seek care. The result, says Calcote, is an overflow of those patients seeking delayed care now, oftentimes needing more advanced treatment and care than they might have needed before their condition worsened — adding more stress on providers.

“Your heart failure and COPD-type patients, you can tell when they’re getting sick enough to where they need to come in. And because they know they’re at higher risk, now they’re waiting longer and they’re waiting until they’re sicker and sicker and sicker, and should’ve been in the hospital five days ago versus now,” he said. “And they’re just sicker when they get here.”

But perhaps most taxing, he says, are the misinformation and mixed messages. Calcote sees politics, rather than science, often leading the virus response, and says it has “led to the whole nation’s just massive failure in getting a direct, standardized message about ‘This is what we need to do’. You’ve got one county doing one thing, one state doing a totally different thing. There’s no standardization across the board,” he said.

He added that when people downplay the seriousness of the virus, don’t take precautions and risk spreading the virus if they have it and don’t know it, it just adds on to the burden the healthcare system is already facing.

“My colleagues and I have been forced to fight a war on two fronts. One, fighting the virus itself and the other fighting this wave of misinformation plaguing social media and news outlets,” he said.

From a medical perspective, though the science is still new, the simple things to prevent spread like masking and distancing are effective, but when there’s conflicting advice from state protocols like increased gathering sizes and mixed messaging about wearing masks, “There’s no way we can beat this thing like that. I mean, there’s so many mixed messages,” he said. “Some states are requiring masks. Some states are outright rejecting mask mandates and it’s just such a cluster. It’s worrisome.”

Adding to higher level care for patients who delayed care over the pandemic’s onset, some hospitals are still operating at lower hospital staffing to recover financial losses. The result is more patients spread across fewer healthcare workers, says Abigail Hartman, an occupational therapist for St. Dominic Hospital in Jackson.

“I haven’t hugged anyone outside of my family since all this started,” Hartman said, adding that adjusting to the new normal has gotten easier over time and she’s feeling hopeful as cases improve. “It’s definitely gotten better. But early on, I basically was living in just a full blown panic all the time and that was in March and April when we didn’t know any information, we didn’t know anything. And then seeing Mississippi be so far behind as far as social gatherings and masks … it was just really anxiety inducing.”

As an occupational therapist, she works with patients who’ve lost their range of motion, typically from a stroke, helping them regain movement and daily activities, like walking or eating. Her job requires both physical and emotional intimacy, to gain trust and help retrain patients’ motion centers — a job highly complicated by COVID-19 logistics, like PPE.

“There’s lots of factors, as far as the normal treatment stuff of trying to talk to a 90-year-old with hearing loss and getting a history, they can’t hear you with the face mask and the shield. And, even just non-COVID patients, having to wear a mask makes it much harder to connect to patients and communicate with them,” she said.

Too, she just has more patients right now, meaning her dedicated time to each shrinks. She went from averaging 13 daily patients to between 16 to 20 now, “which is not normal,” she says. “Pre-COVID when I had 12 to 14 patients, I could spend longer (with each patient). And nowadays, it’s more crunch time trying to see as many people as you can in a short amount of time,” she said.

Hartman says the hospital’s staffing, mask rules and testing protocol make her job harder, but, like most health care workers will relay, she loves her job, despite the chaos and policies she feels aren’t going far enough to protect staff. The hospital only requires N-95 masks — the most protective model if worn correctly — during certain procedures. Even though Hartman works with some patients on COVID wards, she wears a fabric medical mask when with patients, as well as other PPE, but no N-95. But only some patients admitted to the hospital are tested for the virus, per St. Dominic’s policy, so she has no way of knowing if she’s working with a pre- or asymptomatic case. And so, is left without extra protection.

She too contracted coronavirus, though there is no way to track her transmission or spread because she said she was never contacted by state contract tracers.

Before she tested positive, she limited social gatherings and did everything by the books — not so much to protect herself, but knowing she could be carrying it without knowing it and didn’t want to spread it.

On Monday morning a St. Dominic’s spokesperson said, “Current supply challenges around N95s, despite our efforts to reprocess, do not support broader use of N95s at this time.” She previously reiterated that the more protective masks are required in areosol-generating procedures, like intubation. Multiple St. Dominic’s healthcare workers have told Mississippi Today that they are actively not allowed the more protective masks during routine care.

In a written statement, Chief Medical Officer Dr. Eric McVey, said, “From the beginning of the pandemic, St. Dominic’s has followed CDC and MSDH guidance on masking for staff … Similar to other hospitals, personal protective equipment (PPE) supply chain challenges have impacted St. Dominic’s. Despite these challenges, our materials management team, in collaboration with our ministry partners across the Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady Health System, works tirelessly to secure the needed supplies to keep our team members safe as they care for patients. Innovative steps such as disinfecting N95 masks for reuse up to 20 times have made a big difference in our ability to meet the needs of our patient care teams.”

Despite operating at constant full-speed, most of the dozen healthcare workers across the state Mississippi Today talked to for this story said that their biggest source of stress is misinformation and inconsistent messaging.

Hartman, from St. Dominic’s, sees it play out outside of work, where acquaintances try to hug her when she asks them not to. She hates to be too “doom and gloom,” she says, but feels like the seriousness of the pandemic is still not setting in for some.

“They’ll say, ‘I’m hugging you anyway,’ — just people not taking it seriously. And, so that was really frustrating. It’s gotten better. Once the (summer) spike hit, I think people kind of realize this is bigger than we thought it was,” she said, but added “it shouldn’t have taken that.”

Faught, the pulmonologist in Greewnood, saw the opposite effect, sensing that some folks didn’t want to socialize with her knowing she was a “COVID doctor.”

Calcote, the Tupelo hospitalist, says messaging from the federal and state government has been inconsistent, confusing patients, family and friends, and even colleagues.

“You feel like you take two steps forward at work and then three steps back when people discredit everything you’re trying to work towards,” he said, referencing people calling the virus a hoax. He notices that people wanting to deny its seriousness point to new data saying, “See, it’s not so bad.”

His response: “Surviving and being 100% OK, or even 50% OK, are not the same thing,” he said. “To those people who question the mortality rate, the false positives — it’s not all just about that. Those things matter, but (it’s also the) long-term effects of this thing and the fact that we’re straining the system and completely overwhelming everything with COVID plus other diseases, plus the flu, which is on its way, by the way — it’s coming soon.”

Dr. Renita Cotton agrees. As a family physician at Mallory Community Health Center in Durant, she works with families with inconsistent access to primary care in Holmes County, who often distrust medical providers in the first place. She has to work overtime to earn and keep that trust, and inconsistent COVID-19 messaging only adds to that distrust, she says.

“We need evidence-based recommendations, and that leads to consistency. We need the people that manage healthcare crises to be healthcare people that have the training to do so,” she said. “In the past it was clear that we were evidence-based, that all of our recommendations were evidence-based and now that is not the case. And so, what it does, it plants seeds of mistrust in our community and we already always had that.”

The state health department has long worried about Holmes County, where both Cotton and medical assistant Webster-Quinn work. So much so that over the summer, they partnered with the CDC to attempt universal testing. The county sees a lot of poverty and not many good jobs — with that, a lot of residents struggle with access to healthy food and disease prevention.

Eric J. Shelton/Mississippi Today

Nurse practitioner Katherine Kirklin, left, collects specimen from Joe Holmes for COVID-19 testing in Lexington, Miss., Thursday, April 30, 2020.

For Cotton, more focus on prevention is needed, but also a culture that prioritizes patients and trust. She sees her patients’ distrust of the medical system and the high rate of poverty in Holmes County as a perfect storm — brought on by decades of neglect, but fueled by the pandemic.

One of her patients died from COVID-19 after she waited too long to seek emergency care because she didn’t trust the system, Cotton says. “She had had a bad experience before, and she was having shortness of breath and called her family,” she said. “They called 911 and when they got there, she had coded. But she waited so long and she told me she was scared to go in — so I knew why she waited so long, because she was afraid.”

The post ‘Forced to fight a war on two fronts’: How healthcare workers say misinformation and messaging worsen the toll COVID takes in Mississippi appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Gov. Fordice, from different era, was judged much more harshly than President Trump - March 1, 2026

- ‘We can only go up from here’: Hope and apathy in Wilkinson County schools - February 28, 2026

- Community discussion grows around 24-hour child care in Hattiesburg - February 28, 2026