Greenwood Leflore Hospital, plagued by financial hardship for years, saw a bright spot this spring when it was selected for a new federal payment status. But a dispute with Mississippi Medicaid could jeopardize the Greenwood public hospital’s ability to keep services open if a resolution is not reached, its leader says.

“Access to services will be reduced for residents of the central Delta region,” Interim CEO Gary Marchand told Mississippi Today. He said no decisions about service changes have been made yet.

The Mississippi Division of Medicaid informed the hospital in June it is recouping $5.5 million overpaid last year to Greenwood Leflore Hospital in state-directed payments, Marchand said. These amounts beef up low Medicaid reimbursements. The payments were high because they were calculated using old data, which did not take into account the hospital shuttering its labor and delivery and intensive care units in 2022.

The amount is not insignificant. The hospital’s total operating expenses were $74.7 million in the 2023 fiscal year, according to an audit performed that year.

Mississippi Medicaid has withheld $2 million so far this year and will continue recovering payments at a rate of $900,000 a quarter beginning in December, Marchand wrote in an Oct. 20 memo sent to hospital employees and board members.

“Supplemental payments withheld to date along with the scheduled quarterly Recoupments will place a significant strain on hospital operations,” Marchand warned.

Additionally, the hospital’s Medicaid tax assessments should have been lower to reflect the reduced service levels, which could have offset about half of the total recoupment, he added.

Greenwood Leflore Hospital proposed several options for repayment to the Division of Medicaid that would buy it time to first begin receiving higher payments for Medicare patients, said the memo. The anticipated larger payments are the result of the hospital’s acceptance to the federal Rural Community Hospital Demonstration Program, which allows selected hospitals to be reimbursed based on their actual costs for inpatient care instead of a fixed amount. The higher payments are expected to begin by the end of the year and retroactively reimburse services provided since May 1.

Next month, the hospital will begin providing skilled nursing care for people recovering after hospital stays, but will not begin receiving the higher payments for these services until late 2026.

The Division of Medicaid advised the hospital in September that it did not agree with the solutions proposed by the hospital, Marchand said in the memo. On Oct. 9, the hospital appealed the decision and requested an administrative hearing on the matter, which has not yet been scheduled.

The Division of Medicaid did not respond to a request for comment.

Greenwood Leflore is one of 30 hospitals overpaid a total of $48 million during the state’s 2024 fiscal year, Marchand said.

Greenwood Mayor Kendrick Cox said he has been working with state and federal lawmakers to resolve the dispute.

“We desperately need our hospital,” he said. “… There’s a lot of people in our community that aren’t financially able to transport themselves or their relatives to other towns or states for health care services.”

The state-directed payments helped to stabilize Greenwood Leflore’s finances after it was forced to close valued services. But now, the closure of those services could put others at risk, and the new payment model hasn’t yet provided the relief it’s expected to.

This is just one piece of what Brock Slabach, chief operations officer of the National Rural Health Association, called the “brutal mix of issues” that rural hospitals, which often have low patient volumes and high overhead costs, face when trying to break even.

“These are different environments than some of our larger, urban facilities,” he said.

Rural hospitals across the U.S. are struggling. Over half of Mississippi’s rural hospitals are at risk of closure or have experienced losses on services, according to a recent report from the Center for Healthcare Quality & Payment Reform.

Greenwood Leflore Hospital serves approximately 300,000 patients in the Mississippi Delta, a region of the state with limited access to medical care, according to its website. The 35-bed hospital operates a physician-staffed emergency room and offers general, vascular and outpatient orthopedic surgery, cancer care and a full suite of diagnostic services.

The hospital has faced a litany of financial challenges over the past several years. Before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the hospital was losing $7 million to 9 million a year, Marchand previously told Mississippi Today.

The pandemic only worsened the hospital’s precarious financial condition. To keep its doors open, the hospital shut down departments and clinics, went up for lease multiple times, drew down millions of dollars in credit, applied for grants from the state Legislature, and pursued a more lucrative hospital designation. In 2023, the hospital suspended the use of 173 beds to control costs, according to an audit.

Marchand, who will step down at the end of the year, repeatedly warned local leaders and state lawmakers that the hospital was on the verge of closure.

To become more financially secure, the facility vied in 2023 to be designated a critical access hospital. These facilities are reimbursed by Medicare at a rate of 101%, theoretically allowing for a 1% profit. But its initial application was denied because critical access hospitals must be located 35 miles from the nearest hospital, and South Sunflower County Hospital in Indianola is closer, at 28 miles away.

Greenwood Leflore was one of three hospitals in the state chosen for the Rural Community Hospital Demonstration Program in April.

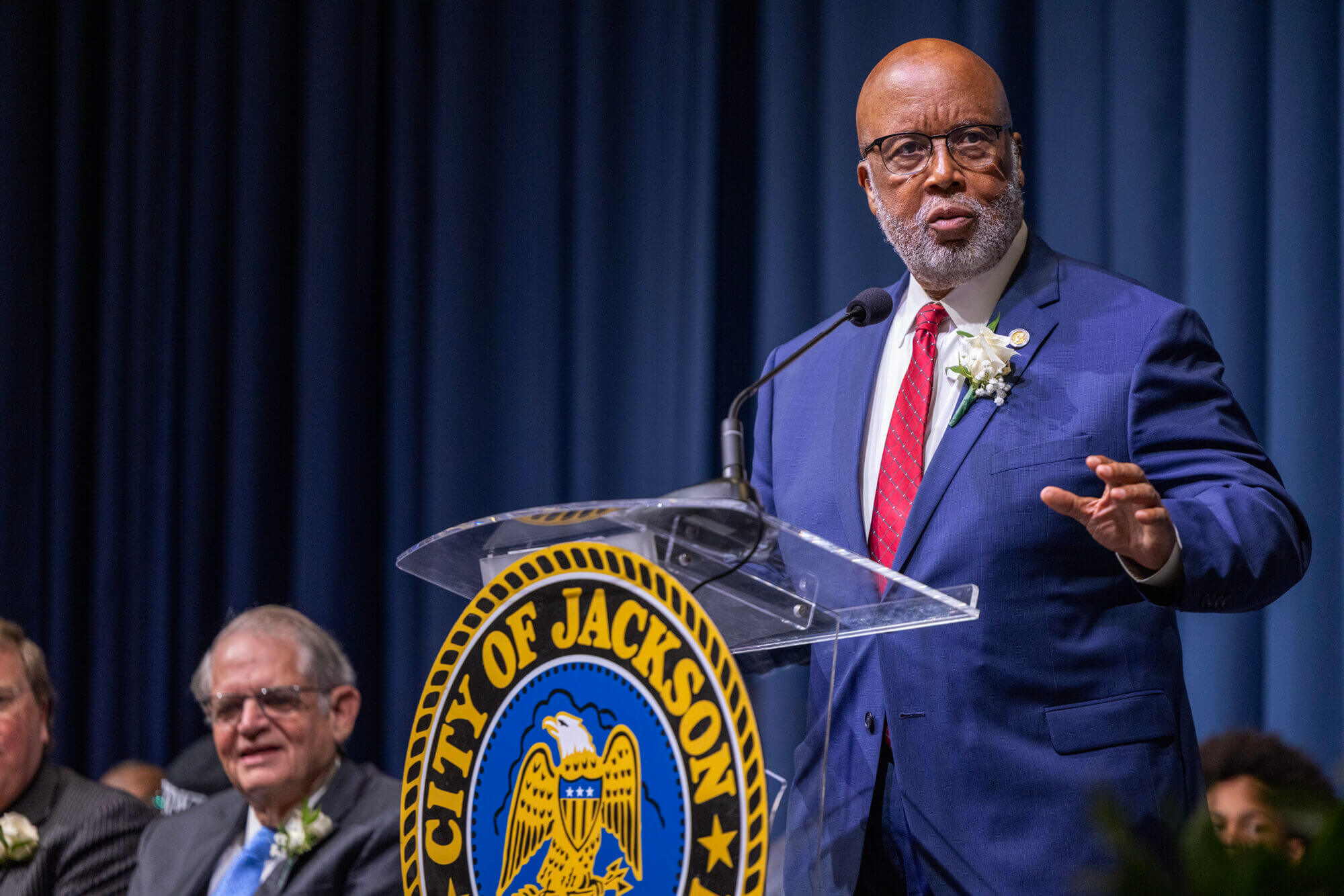

Democratic U.S. Rep. Bennie Thompson called the designation a “meaningful victory.”

“For far too long, rural hospitals have operated at a disadvantage, being underfunded, understaffed, and overburdened,” he said in a statement. “This program is a step toward leveling the playing field.”

The program’s payment model can help stabilize rural hospitals, but it only increases reimbursements for inpatient care — even though many hospitals are seeing higher outpatient volumes, said Slabach.

And the reimbursement challenges rural hospitals face are worsened by workforce shortages, since rural hospitals often have to offer higher pay to attract providers — money they don’t have due to low reimbursement rates.

“It’s a vicious circle,” Slabach said.

State-directed payments like those recouped from Greenwood Leflore Hospital, which were championed by Republican Gov. Tate Reeves, have been a vital source of cash for Mississippi’s struggling rural hospitals, especially in a state that has gone a decade without expanding Medicaid.

But those payments are set to be reduced over time beginning in 2028 as a result of federal cuts to Medicaid included in the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” signed by President Donald Trump in July.

Mississippi is expected to receive at least $500 million over the next five years as a part of a major federal investment meant to offset the cuts’ impact on funding for rural health care. States must submit applications for the funding to the federal government by Nov. 5.

The funding aims to strengthen access to health care by investing in lasting improvements to preventive medicine, collaboration between health care facilities, workforce development and innovations in care and technology.

“It could well be a lifeline for a lot of hospitals that are struggling,” said Harold Miller, the director of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform.

But the money is a one-time, lump sum, and there is no telling how states will choose to spend it or if it will go to struggling rural hospitals, he said.

Reeves is responsible for the state’s one-time application for the funding, which is due in less than two weeks.

- ‘We can only go up from here’: Hope and apathy in Wilkinson County schools - February 28, 2026

- Community discussion grows around 24-hour child care in Hattiesburg - February 28, 2026

- Democrats say FEMA’s pause on long-term recovery projects is ‘just being mean’ - February 28, 2026