CLINTON — There’s still so much James Robinson doesn’t know about the woman in the photograph.

It was always on the wall in his aunt’s house, but he never knew who she was until he found a news article about her. Now, he gets to share her story.

The woman’s name is Sally Lee, a witness and survivor of the 1875 Clinton Massacre. Robinson, a 76-year-old retiree and Clinton native, is her great-great-great grandson.

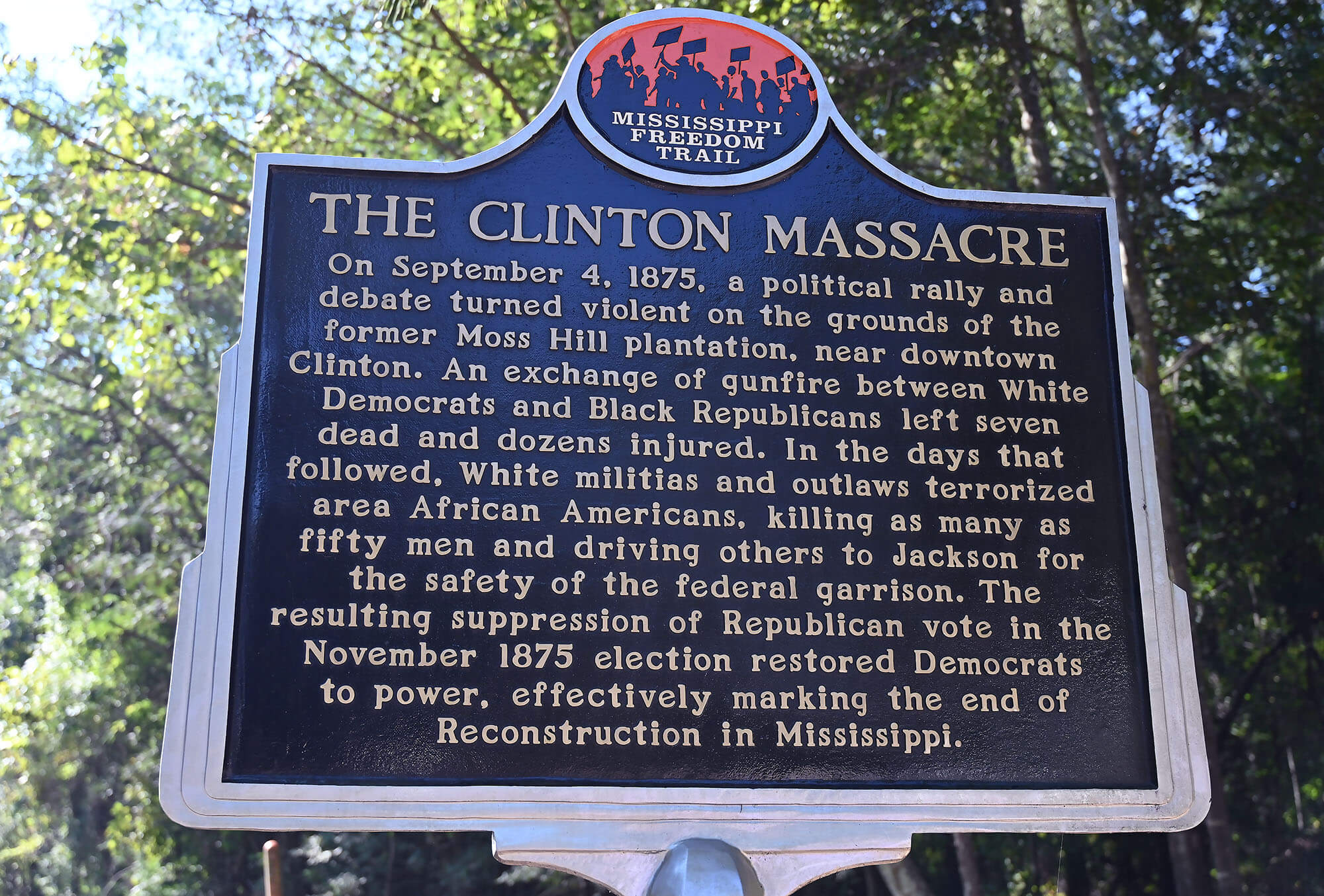

On Sept. 4, 1875, a Republican political rally in Clinton turned into a tragedy when white disruptors fired into the crowd, killing multiple people. What followed was several days of racist violence that helped bring Reconstruction in Mississippi to a bloody, tragic end.

Last week scholars, political figures and descendants of victims and survivors came together to commemorate the massacre’s 150th anniversary.

DeeDee Baldwin, an engagement librarian and associate professor at Mississippi State University, organized the commemoration events. She learned about the Clinton Massacre while researching Black state legislators during the Reconstruction era.

“It’s a pivotal event, not just in Mississippi history but in national history, and hardly anybody knows about it,” Baldwin said.

Commemorations took place last week. On Wednesday, Baldwin joined a panel of historians to discuss the massacre during a “History is Lunch” event at the Two Mississippi Museums. On Thursday morning, there was a brief reflection at the historical markers for the massacre, followed that evening by another panel at Mississippi College. Descendents of the massacre’s victims and survivors spoke at a memorial service at Mount Hood Missionary Baptist Church on Saturday.

The events were sponsored by Mount Hood Missionary Baptist Church, Mississippi College, Mississippi State University’s Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library and Together for Hope.

Sen. Hillman Frazier, a Democrat from Jackson, authored a Senate resolution to recognize the massacre’s anniversary. He spoke at the commemoration event on Thursday morning, emphasizing the importance of political participation.

“They didn’t have more bullets than the opposition, but they had the vote,” Frazier said. “Make your vote count.”

At the markers on Thursday, Robinson carried around a copy of Lee’s picture in a clear sheet protector. On the back of the page was a copy of an article from 1961 that The Clarion Ledger published about her life. This article, which inspired him to start learning more about her and his family’s history, retells notable stories in Lee’s life, including how she and her son survived during the Clinton Massacre.

The bloodshed occurred during the Reconstruction era. Before the partisan political makeup of today, the Republican Party was majority-Black and controlled much of state politics. Black men in Mississippi, granted voting rights and the ability to hold office by the federal government post-Civil War, had been voting for years and many held elected offices.

These post-war realities did not sit well with white Southern Democrats, who sought to restore white supremacy by any means necessary. In 1875, they devised the Mississippi Plan, a strategy to use fraud and brutal violence to suppress the Black vote and reestablish Democratic control of Southern state governments.

The fateful day in Clinton began as a political rally and picnic held by Mississippi’s Republican Party ahead of the 1875 statewide elections.

About 1,500 to 2,500 people were in attendance, most of them Black families. Eighteen of the approximately 75 white attendees were Democrats. They were part of the White Liners, what was essentially a paramilitary unit for the state Democratic Party.

In an effort to preserve peace, the Republicans allowed Democratic Senate candidate Amos R. Johnston to speak at the event. However, when Republican newspaper owner and Union veteran Captain H.T. Fisher spoke, according to news accounts of the day, he was heckled and tensions quickly turned into bloodshed.

Gunshots rang out in the crowd. Many white Democrats fell into formation and fired into the crowd. At the rally, three white people and four Black people were dead, and six white people and 20 Black people were wounded. Black women and children frantically ran for safety.

One of them was Lee, who ran with her son in her arms. Spotting a hollow in a sycamore tree, she placed the baby there and hid until it was safe.

Clinton’s white mayor at the time had called for assistance from towns nearby based on a rumor that armed Black people would storm the town. By nightfall, several hundred White Liners entered the town. They spent the next day hunting, beating and killing Black residents. During this time, an estimated 50 Black people had been killed.

In 1876, a congressional report debunked the Democrats’ narrative that the massacre was an attack on white citizens by armed Black Mississippians. They found instead that white Mississippi Democrats plotted to disrupt Republican political activities and “to inaugurate an era of terror.”

By 1877, Reconstruction was over and the last federal troops left the South, allowing white Democrats to regain political power and establish the most stringent of laws to suppress and endanger Black Mississippians during the Jim Crow era.

Today, 150 years later, Baldwin hopes people who learn about the story realize “the importance of participating in democracy and protecting it.”

Frazier emphasized this point when speaking at the historical marker on Sept. 4. He also spoke out against anti-DEI legislation, saying it held up progress for women and Black people. This sentiment has become particularly pronounced in recent weeks. Last month a federal judge struck down an anti-DEI guidance from the U.S. Department of Education. Another federal judge blocked Mississippi’s anti-DEI law for the foreseeable future, concerned it would violate Mississippians’ constitutional rights.

Three years prior, the state enacted a ban on teaching critical race theory in schools and universities. Mississippi Today reported last week that the University of Mississippi and Mississippi State University halted funding for student organizations amid uncertainty over the law.

“They want to sanitize history,” Frazier said at the Clinton Massacre markers. “But we have to make sure we tell history the way it was.”

Robinson, still holding on to that photo of Lee, expressed hope that people attending the commemorations learned that “there’s a good side and a bad side to human beings, and you have to choose which side that you’re going to be on.”

- Sen. Wicker writes to Kristi Noem opposing feared ‘ICE warehouse’ in Byhalia - February 4, 2026

- House votes to legalize online sports betting and divert $600M to pension system - February 4, 2026

- Lawmakers push bills to heighten transparency for rural health federal funding - February 4, 2026