Maria was seven months pregnant with her now 12-year-old child when she slipped on the greasy floor of a Koch Foods poultry plant in Morton. She fell over, got back up, and resumed working. She had 40-pound boxes of freshly packed chicken to carry roughly seven minutes from the line to the frying area.

The further along in her pregnancy, the harder it was to do her job – and the more scared she was for herself and her baby. She asked to be moved to a less intensive position for the rest of her pregnancy. Her supervisors refused.

She says they asked her to present a doctor’s note before they allowed her to take more bathroom breaks than the one per shift granted to all workers.

“They don’t move you to another position, even if you have a fever, even if you’re crying,” Maria said. “Because they say, ‘It’s your job, you already know your job.’”

So she kept clocking in at 6 a.m. until she was eight-and-a-half months pregnant.

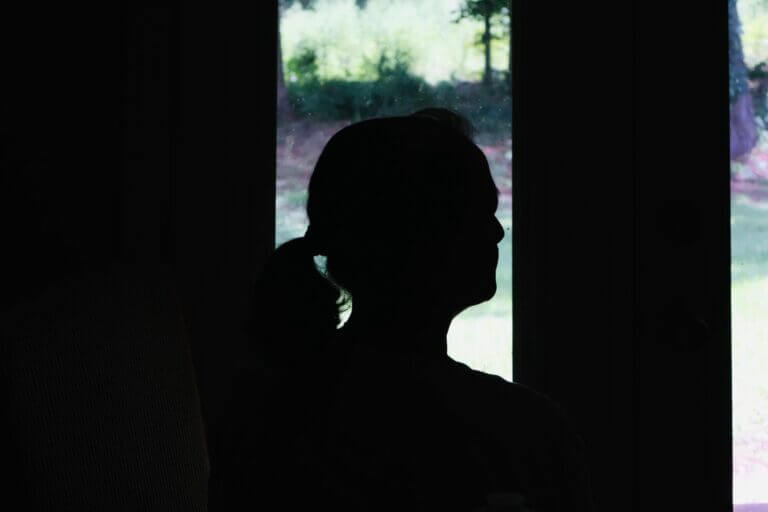

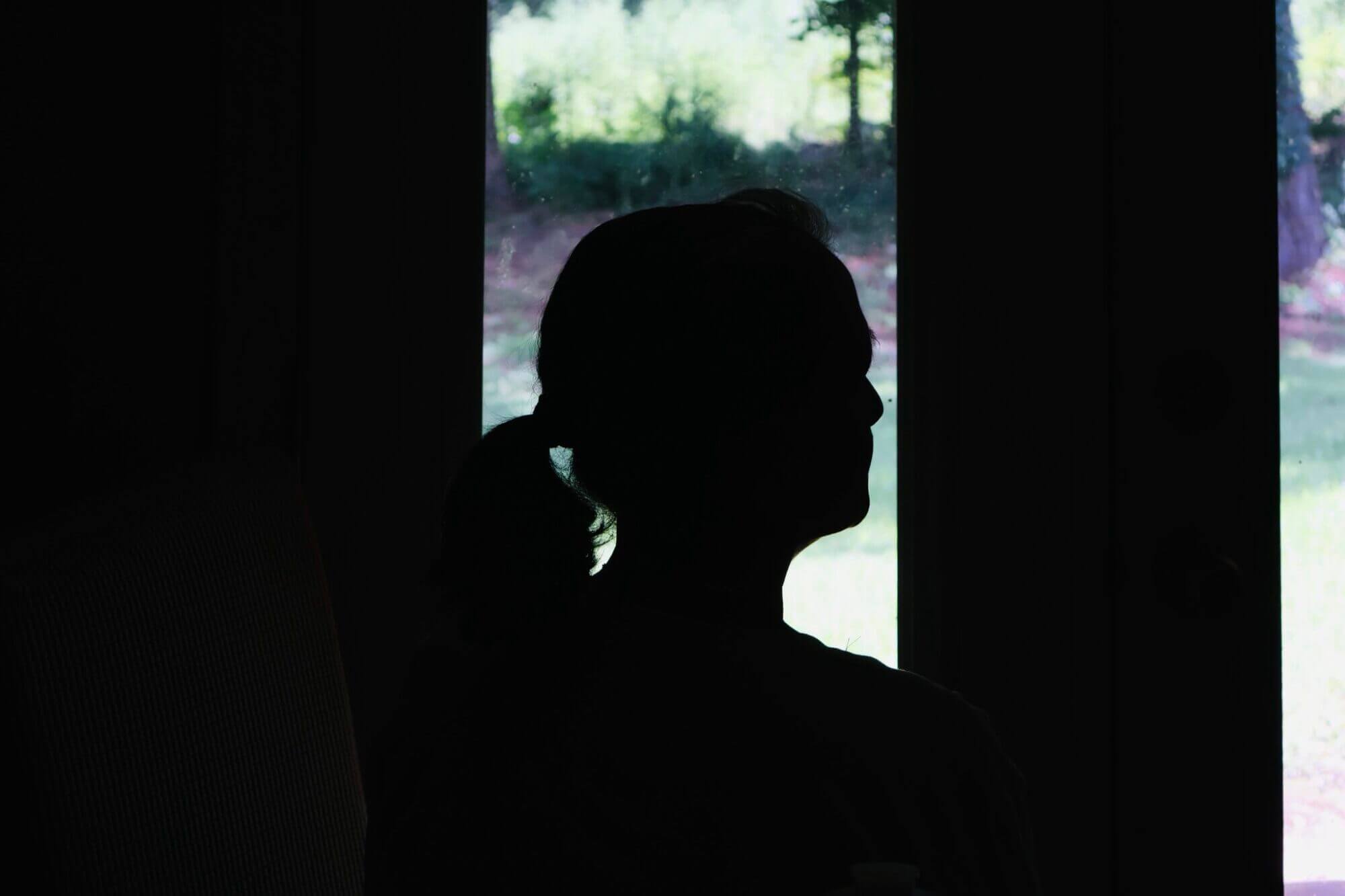

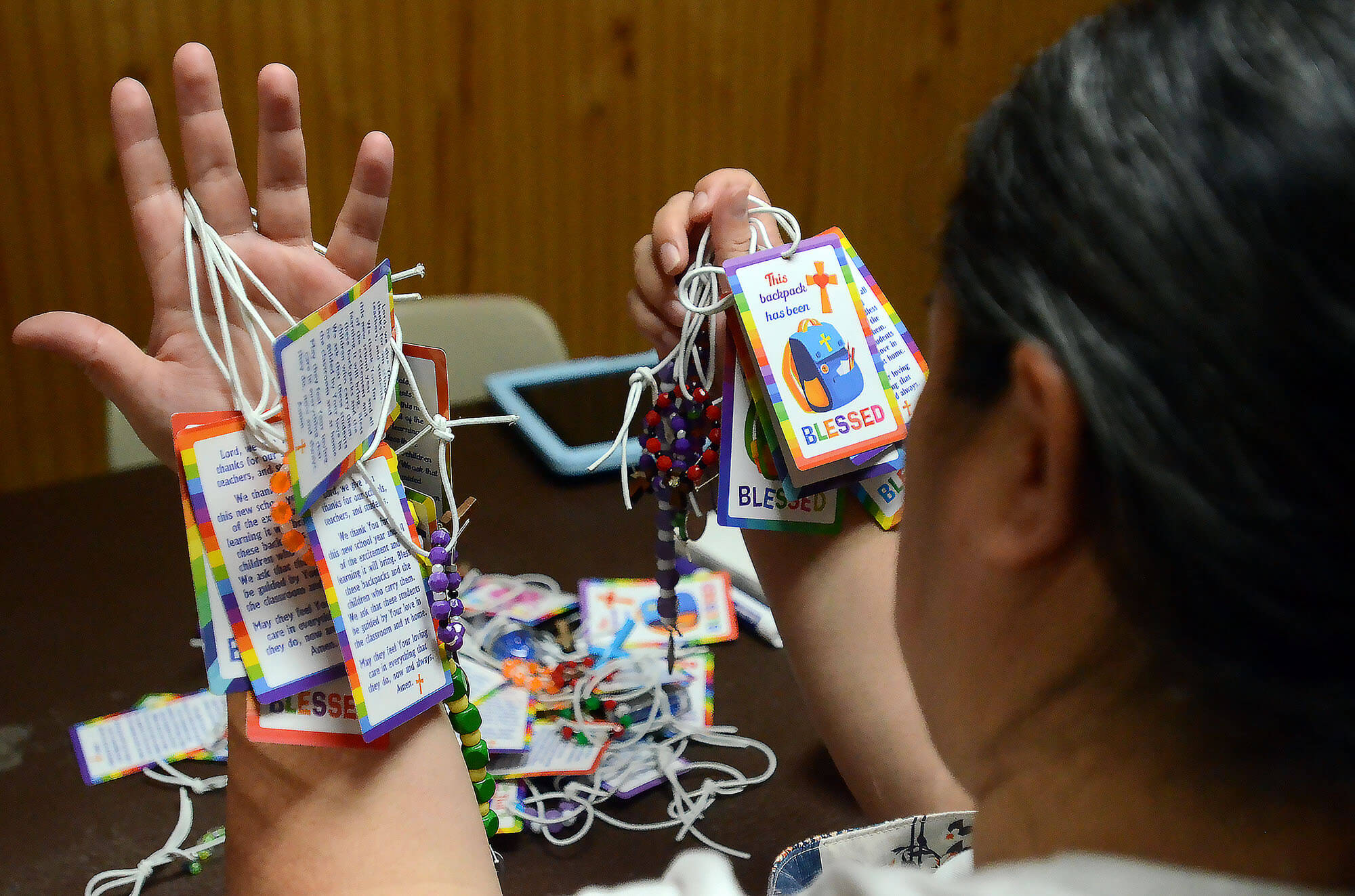

Six years after Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids on seven Mississippi poultry plants brought national attention to an industry that had profited from undocumented labor for decades, more than a dozen current and former immigrant workers told Mississippi Today that deteriorated working conditions persist for undocumented employees as well as those with work permits or green cards. Most interviews were conducted in Spanish, with some workers’ first names changed and their last names not used because they feared retaliation and deportation.

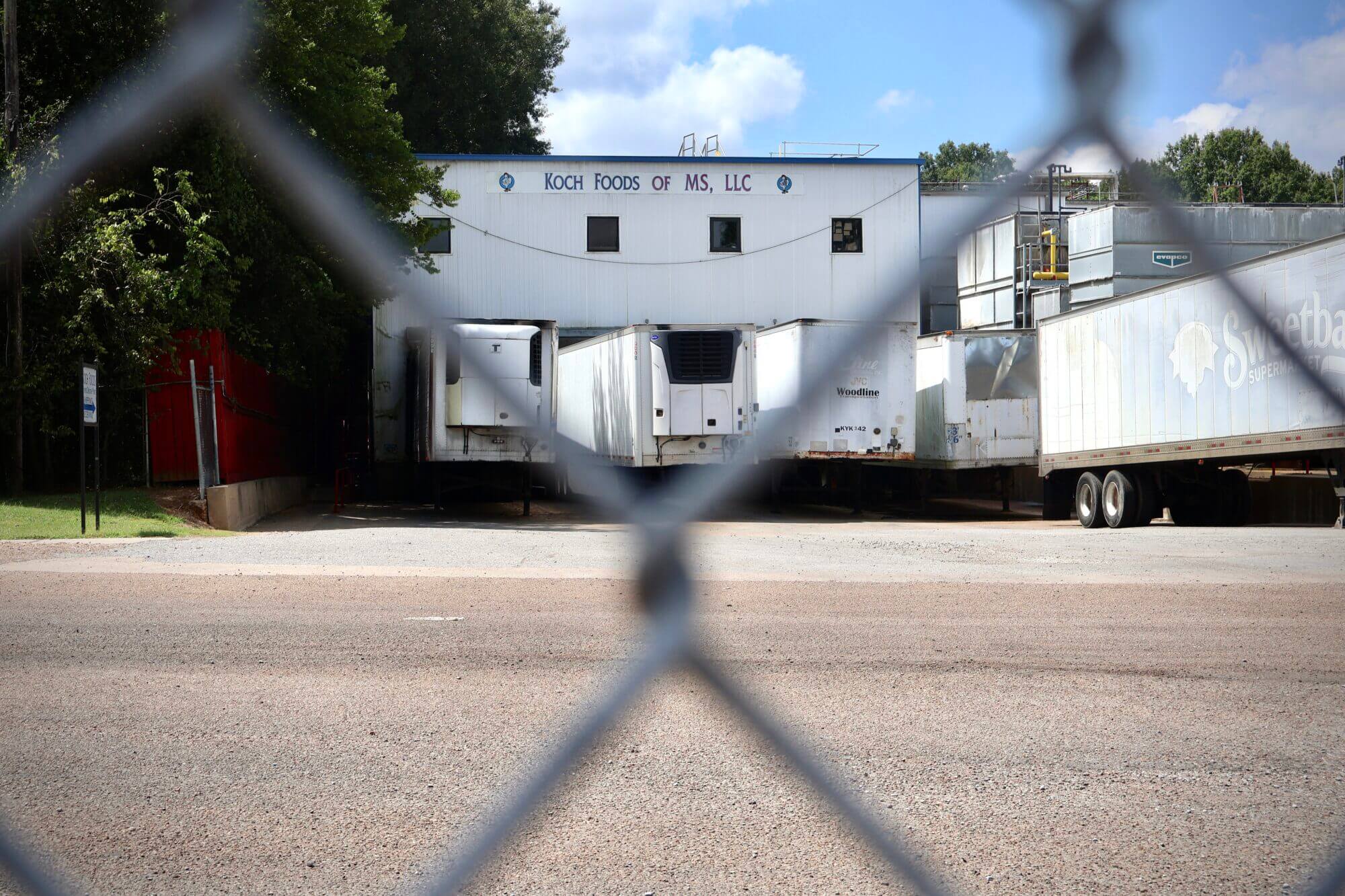

ICE detained 680 mostly Latino workers in the August 2019 raids. The year prior, Koch Foods settled a class action lawsuit for $3.75 million. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission charged the company with sexual harassment, national origin and race discrimination as well as retaliation against Latino workers at its Morton plant.

Following the raids, three plant managers and human resources staff were sentenced to up to two years of probation for knowingly “harboring illegal aliens.”

Years later, loopholes persist. Several workers told Mississippi Today it is still possible to find employment in the chicken plants without work authorization, often using fake papers or a contractor.

This practice isn’t unique to Mississippi. In 2024, nationally, around 23% of workers in the meatpacking industry were undocumented and 42% were foreign-born, the American Immigration Council told Wired Magazine. Undocumented immigrants represent 4.6% of the U.S. employed labor force.

“They seek out the most vulnerable workers, who are not going to complain and not going to demand better conditions,” said Debbie Berkowitz, a former policy adviser for Occupational Safety and Health Administration and worker safety expert who has written about the poultry industry.

Before obtaining a work permit in 2021 and finding employment in a Tyson plant, Gabby worked for two other poultry processing companies under a fake name. She paid a U.S. citizen $1,700 to use the person’s Social Security number and name at work.

Koch Foods, her first employer, hired her in 2006 through a third party. The only form of identification required was that Social Security number.

Her contractor, a single person who operated through word of mouth, didn’t provide her with a contract – only paying her cash. When he held her pay for over a month, Gabby complained to plant managers. They said her salary wasn’t processed through the plant’s payroll department and they were not accountable.

“The first thing most people think is, if I speak up, ICE is going to come for me,” Gabby said. “The last thing you want to do is create problems. What you want to do is work.”

In order to keep her job, she had to lie and maintain a fake identity. She lived in fear of being found out.

“You go to work with fear, you go with shame,” she said.

Working with fake papers can make getting a doctor’s excuse for missed days nearly impossible. Maria was able to get six weeks of unpaid maternity leave with a doctor’s note because she worked under her real name, but other pregnant women needed a doctor who agreed to forge their fake name on medical records.

Gabby says she was fired from her job at Koch Foods because she gave the contact information of a willing doctor to other undocumented workers. Koch Foods didn’t answer multiple requests for comment on allegations made by workers.

Past the limit

Across all assembly lines, the piece rate – the number of chickens that workers handle per minute – directly affects the likelihood of developing pains or muscle and bone injuries, a study funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture found. Only the evisceration line speed, or the phase where chickens are killed, is federally regulated. Piece rate is determined mainly by the job-specific line speed and staffing level.

The same study found that 81% of U.S. poultry plant workers had an “unacceptably high” risk of musculoskeletal disease. To mitigate that risk, authors recommended increasing staffing levels and decreasing line speeds.

But several workers said line speeds were used to increase pressure on employees. Miguel, an 18-year Koch Foods employee, claims he was pushed to resign within months by a supervisor who continuously increased line speeds as punishment.

He started in 2000 in the debone section, cutting chicken parts from hanging carcasses, then became a lead person. For an additional $1 per hour, he was watching over two lines of 30 workers in total. He says he was demoted by this new supervisor who took a dislike to him.

The supervisor would single him and another employee out, place them on another line and speed it up.

“He told me he wanted us to do double duty: What four people were doing, he wanted two to do,” Miguel said.

After three failed attempts to report the situation to managers, Miguel quit and found work in construction. Koch Foods did not provide comment on how line speeds are set and managed at the plant.

Every worker interviewed described as routine hostility from supervisors and managers, harassment and arbitrary punishments targeting immigrant workers.

“I feel like it doesn’t matter if you speak English or not, they’re going to look at you ugly. They treat you wrong just because they feel they have that authority, that they’re the boss,” said Sofi, a recipient of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. She started working at Koch Foods in February and quit after four months.

Injured and fired

Annual employee turnover averages 65% but ranges as high as 150% in poultry plants nationally, according to a survey by the U.S. Poultry and Egg Association. Over half of employees last less than three months on the job.

Employees told Mississippi Today that almost anything can be grounds for termination. Half of the dozen workers interviewed said they witnessed or experienced layoffs following an injury on the job.

Repeating the same motions hundreds of times a day, for years, can lead to chronic pains and eventually injuries. Maribel, a 17-year Koch Foods employee, tucked chicken wings for eight years with an overstretched tendon in her hand. With the pain on her mind, she says she was terminated in March after she requested to not be moved to the more intensive deboning section, where workers handle large metallic scissors.

Idalia, a green card holder, says Tyson Foods fired her after she reported a dislocated shoulder with a doctor’s note in 2023. She marinated chicken, a job that requires repetitive hand and arm movements. She now works for Koch Foods, where she packs boxes of chicken with growing pain in her hand from knocking her hands against tape dispensers and frozen chicken six days a week.

Poultry plants are required to report injuries needing treatment beyond first aid or resulting in lost work days to OSHA. Lost work days must also be reported to the Mississippi Workers’ Compensation Commission.

Mississippi law states that all injured workers, regardless of immigration status, are entitled to workers’ compensation, and medical and wage loss benefits, even if they get fired following the injury.

However, undocumented workers are less likely to claim the benefits, due to a lack of information and fear that drawing attention to themselves could lead to deportation.

Several employees told Mississippi Today that some plants found a way around reporting injuries to OSHA.

A bad fall on his hips in a Koch Foods plant injured Miguel enough that he couldn’t work for two weeks. While recovering, he came in every day, clocked in and out at his regular hours, pretending to be working as usual. For the entirety of his shift, he sat in the rest area.

His managers said it was the only way he could get paid while he was injured.

Three workers interviewed said they witnessed injured employees sitting all day in the cafeteria or their supervisor’s office. Koch did not respond to a request for comment.

“I think not wanting folks to report is an OSHA question, and then not wanting folks to get access to medical care and disability benefits is a money question,” said Angela Stuesse, author of “Scratching Out a Living: Latinos, Race, and Work in the Deep South,” based on years of ethnographic research in Mississippi’s poultry region.

Exposed to hazards

Ninety-one severe injuries were reported in Mississippi’s poultry plants in the last 10 years, and 35 workers suffered amputations. Poultry workers nationally suffer occupational injuries and illnesses six times more often than other workers, according to 2016 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But the prevalence of injuries in the industry is not a natural consequence of handling dangerous machines, tools or chemicals. Berkowitz argues it is the result of companies purposefully cutting corners to save money.

“All injuries are preventable,” she said. “It’s all about profits, and they’re making huge profits.”

Tyson Foods, the biggest chicken producer in the U.S., reported $16.4 billion in chicken sales in 2024.

The sanitation shift, which takes place at night and is mostly staffed by undocumented workers, is the most dangerous, Berkowitz says. Workers clean the blood and guts out of machines, using high pressure hoses and corrosive chemicals. But some poultry companies use sanitation subcontractors to clean their plants, escaping some liability for what happens on the shift.

“This is really a way to outsource their obligation to protect workers,” Berkowitz said.

Although company employees still oversee operations, subcontractors are responsible for hiring workers and providing them adequate equipment and training.

Quality Service Integrity, a sanitation company contracted by Tyson Foods, was fined $10,000 in June 2024 for making workers pay to replace their damaged protective equipment, like chemical suits and safety glasses, in a Tyson plant in Carthage – a violation of OSHA standards.

The same investigation also found that the plant did not have an infirmary or a person trained to perform first aid.

Baldomero Orozco, an employee with a work permit who cleaned Tyson’s Carthage plant at night, had filed a complaint against Quality Service Integrity to OSHA before the inspection.

“We have strict policies in place across all facilities to ensure full compliance with all applicable workplace regulations,” a Tyson Foods spokesperson told Mississippi Today in a statement. Quality Service Integrity did not reply to a request for comment.

The same year, Orozco filed another complaint against Peco Foods in Sebastopol, his previous employer, claiming they charged him for tools and other equipment required for the job. He told Mississippi Today he spent roughly $150 on tools alone.

“The company didn’t take responsibility for anything for us,” he said. “We had to buy our tools, the wrenches, everything you use to remove a screw.”

Peco Foods had previously been fined $6,000 in May 2023 for failing to replace workers’ equipment at no cost.

Enforcement failures

Occasional citations might be one-time victories for workers, but Orozco says they do not lead to long-term improvement.

“When OSHA came by, things did calm down, more or less. But after a couple days, the same things started happening, because OSHA never followed up on the case,” he said.

Quality Service Integrity’s operations with Tyson in Carthage have not been inspected again since the citation was issued.

OSHA’s data reveals that inspections in Mississippi’s poultry plants are scarce. Tyson Foods plants were not inspected for four years before Orozco’s filing. Koch Foods was inspected twice in the past five years.

A report published by a federation of labor unions in April stated it would take 243 years for Mississippi’s seven OSHA inspectors to visit every workplace once.

“Most workplaces never see OSHA unless a complaint is filed, or a worker is killed, or there are very serious injuries that are reported,” Berkowitz said in an email.

Nine of the 20 inspections performed by OSHA in Mississippi’s poultry plants in the past five years were initiated by a worker complaint. Mar-Jac poultry plants were inspected three times following the death of a worker in three years – and fined $163,759 in 2023 after the death of a 16 year-old on the job.

“OSHA’s top priority for inspection is an imminent danger –- a situation where workers face an immediate risk of death or serious physical harm,” a Department of Labor spokesperson said. Second priority goes to fatalities or accidents where three or more workers are hospitalized. Employee complaints come next, the spokesperson said.

OSHA typically does not give advance notice of an inspection, except in certain specific situations. But when OSHA inspectors come unannounced, plant managers can refuse to let them in and ask them to come back with a warrant.

Maria, who resigned from her job at Peco Foods in Sebastopol after she broke her spine in a car accident in December 2022, is unable to work today. Because she got injured on her way to work, she was eligible for workers’ compensation. But she never claimed it, in fear of upsetting her employer.

“I was scared,” she said. “What if they call the police or ICE on me?”

Awaiting surgery in hopes of getting fully back on her feet, Maria struggles to make ends meet for herself and the three children she’s raising alone.

“I don’t have a work permit, I’m just another immigrant, but I fight. I fight every day to raise my children. I don’t depend on the government,” she said.

Leonard Bevilacqua contributed to this report.

Lili Euzet, a French trilingual reporter, joined Mississippi Today for a 10-week fellowship through the University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism.

- Ole Miss QB Trinidad Chambliss’ NCAA appeal is denied, but legal fight over eligibility continues - February 5, 2026

- Visitor brochures are returned to Medgar Evers home - February 5, 2026

- Advocates demand fix for Mississippi’s child care crisis - February 5, 2026