What would happen if every mother in Mississippi – or in Mississippi’s neediest counties – received no-questions-asked cash assistance during pregnancy and months after a baby is born? Lawmakers pondered these questions at the state Capitol Thursday.

The conversation focused on a program called Rx Kids, that started in Flint, Michigan, and is branded as a “prescription to poverty.” Dr. Mona Hanna, the program’s founder, presented her initiative to Mississippi lawmakers in House and Senate Public Health committees as a way to combat infant mortality. Nationwide, infants die at a higher rate in Mississippi than any other state.

Mississippi doctors offered context during the hearing on rising infant deaths. In August, the state health department declared a public health emergency, and this week, doctors urged lawmakers to think creatively in how they choose to address the crisis.

“Every hour that goes by, every day that goes by when a baby is born without the resources they need is a failure on all of us – we can do better,” Hanna said. “We don’t have to be OK with babies dying because of deprivation. This is not a genius idea, it’s not a new idea, it’s not a radical idea – this is just common sense.”

Rx Kids gives $1,500 to moms during pregnancy and $500 a month for six to 12 months after birth. This program only applies to mothers in the perinatal window in select communities, unlike a universal basic income, which would be available to everyone in theory. However, it is similarly unconditional – requiring no proof of income or employment and making no stipulations about how the money is spent. In Michigan, the program has given over $17 million to nearly 4,000 families in 11 communities to date – and the preliminary data bodes well.

Rx Kids is administered by GiveDirectly, a global cash assistance program funded by a number of private foundations and government institutions. At one point, this list included the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Senate Public Health Committee Chairman Hob Bryan, a Democrat from Amory, said the program showed “great promise,” and House Public Health Committee Chairman Sam Creekmore, a Republican from New Albany, said he intends to “float the idea out to the Legislature.”

“My initial thoughts are that it’s great,” Creekmore said. “It comes down to can we afford it, or can we not afford it – but we can’t ignore it. It’s proven, successful and something I wanted to bring to the table today.”

Cash assistance programs similar to what Hanna described have demonstrated usefulness and public appeal. During the pandemic, the nation briefly had a cash assistance program for parents through the expanded child tax credit. The program helped reduce childhood poverty to a record low of 5%. After members of Congress failed to extend the program, childhood poverty has surged to a new high of 12%. Had Congress voted to continue the program in 2022, an analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found 3 million children could have been kept from poverty.

The U.S. is exceptional among wealthy nations for its high rate of childhood poverty. Evidence shows that when children endure poverty, they also are at greater risk of experiencing emotional dysregulation, obesity and malnutrition. These conditions are significant contributing factors to developing chronic diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes and cancer. In Mississippi, one of the poorest states in the nation, nearly 1 in 4 children live in poverty.

Around childbirth, expenses increase while income decreases for parents, making it a uniquely difficult time. The United States offers no national paid parental leave policies but produces the highest costs in child care globally, according to the World Economic Forum.

The program Rx Kids has helped alleviate some of those crushing costs for young families in Michigan. The number of infants staying in the neonatal intensive care unit, as well as those born underweight, dropped by more than a quarter, while preterm birth dropped by 18%, according to a study conducted on the program in Flint. In addition, evictions fell by 91%, and postpartum depression and nutritional access improved by 14%.

Mississippi doctors are encouraged by these data and how a program like what Hanna has launched could boost quality of life for young patients and caregivers. Dr. Patricia Tibbs, a Laurel pediatrician and president of the Mississippi Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said she is sold on the program, calling the premise and the results so far “amazing.”

“It seems like it shouldn’t work, but it works,” Tibbs told Mississippi Today. “There’s something that happens when a child is not born into absolute poverty, when that first year or two years of that child’s life is stress-free. It makes a huge difference in this child’s trajectory in the future.”

Given her understanding of child development and psychology, Tibbs believes even a temporary alleviation of poverty is worth it, because of the dramatic long-term effects that it can have on health and wellbeing.

“The security of a check for a few months is enough to make you realize the possibilities,” Tibbs said.

Dr. Anita Henderson, a pediatrician in Hattiesburg and former president of the Mississippi Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said this program would help many of the patients she sees.

“Transportation is an issue, child care is an issue, missing half a day at work is financially not feasible for many of my families,” Henderson said.

During the hearing, Rep. Dan Eubanks, a Republican from Walls, raised concerns about the “lack of accountability” in the program.

“If we’re trying to incentivize better behaviors, but we’re just giving them money, how does that incentivize them to correct some of the underlying causes of infant mortality?” Eubanks asked.

Hanna said research shows the program led to an 11% decrease in smoking in the third trimester – something she attributes in part to a reduction in stress.

“We didn’t create a complicated program to tell people to stop smoking – but people are on their own,” Hanna said. “Because moms by and large know what they need to do. They know what’s important, everybody loves their babies, and they want healthy babies. If you just give them a little bit of an economic cushion during this window, we see all these improvements.”

In Michigan, the absence of bureaucratic and systemic barriers allowed the program to garner bipartisan support. Michigan Sen. John Damoose, a Republican who represents a rural swathe of northern Michigan, recalled going from a skeptic to a champion of the program.

“My immediate first thought was, ‘I’m a Republican – we don’t support giving away free money,’” Damoose told Mississippi Today. “But, as a pro-life Republican, I did wonder whether this program might give some young mothers the courage they need to choose life, so I decided to dig a little deeper. What I found was a brilliantly crafted initiative that was totally efficient and through its simplicity, addressed some of the most critical needs facing young families and children throughout our society.”

Damoose said he found the economics of the program compelling, since it “avoids the massive costs of bureaucracy.”

The program has almost no overhead. Once the money is allocated, there is very little that states have to do to administer it. Hanna estimated a pilot program in two Mississippi counties would likely require two staff members on the ground.

“We are not hiring offices of people to figure out who’s in, who’s out, who’s deserving, who’s not deserving,” Hanna explained. “Plus, everybody needs help during this window. That’s why this program is more focused on poor places, rather than poor people.”

In Michigan, the program is made possible through a combination of state funds, federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds, and philanthropic funds.

Mark Jones, director of communications at the Mississippi Department of Human Services – which oversees the TANF program – said they have not allocated any money toward the program and won’t know whether they have the funding to do so until early 2026.

“We have been approached by those who have operated the program in other states and are always open to hearing solutions that would benefit Mississippians,” Jones said.

A private foundation called The Families and Workers Fund, headquartered in New York, has already pledged $2 million to implement the program in Mississippi – contingent on the state putting up funds, Hanna said. The state’s funds don’t have to be TANF funds, and they don’t have to be a direct match – it could be less than $1 million.

“About $2.5 million is needed to start a pilot program, and we have $2 million,” Hanna said.

The use of philanthropic funds means the assistance counts as a gift, rather than income. That saves people from falling off “the benefits cliff,” a phenomenon where needy families who see a small increase in income get kicked off of social safety net programs, such as Medicaid or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

This kind of direct investment in families influences outcomes beyond poverty or infant mortality, Hanna said. It bolsters community and strengthens public trust in government.

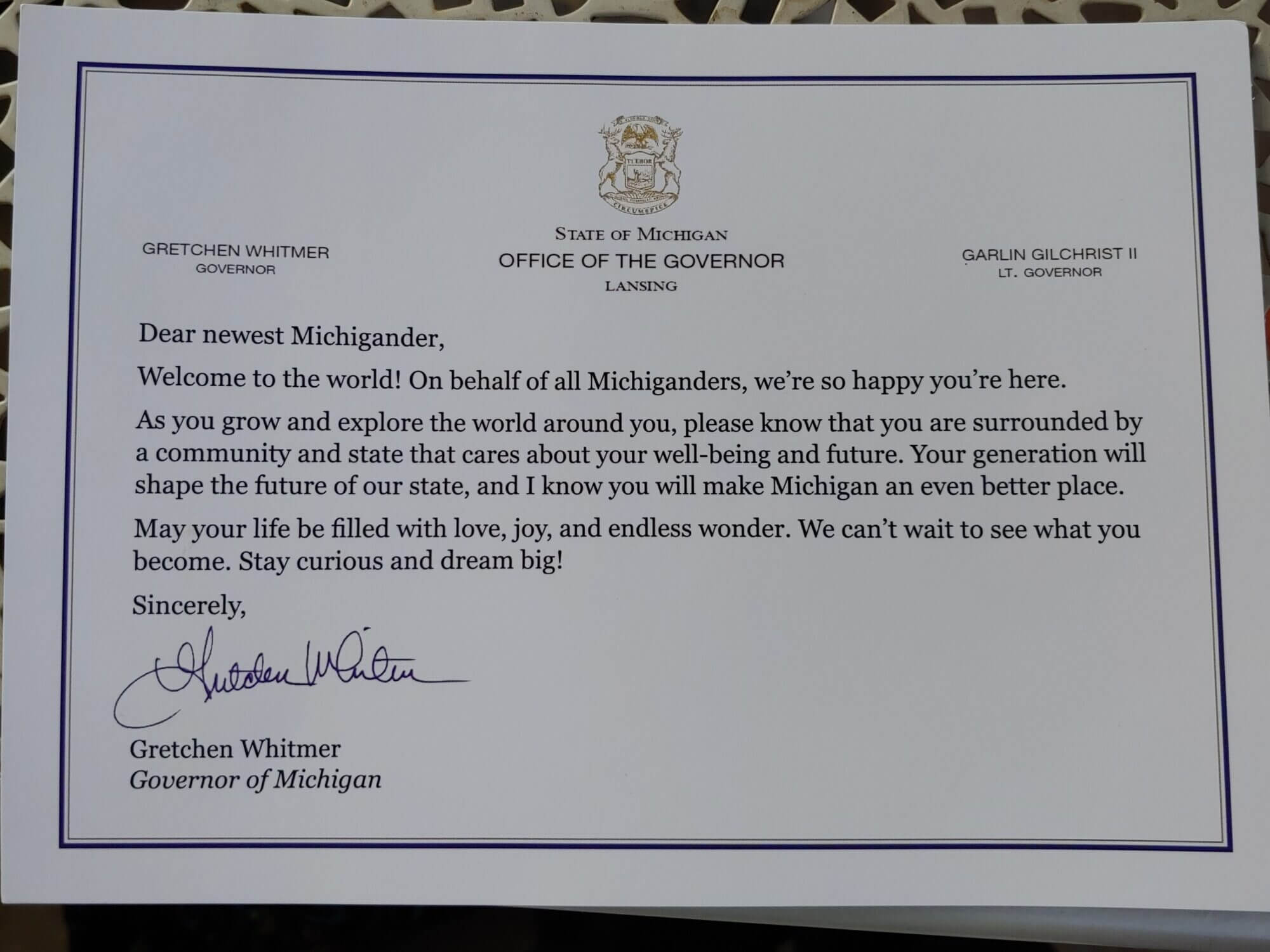

“As much as we are eliminating poverty and improving health, we are sending a message,” Hanna said. “This is all very much about shifting the narrative about how we can care for each other. We are literally telling people: ‘We love you, we are investing in you, and we cannot wait to see what you become.’”

- Scientists: Genetic analysis could speed restoration of American chestnut trees, from Maine to Mississippi - February 14, 2026

- NAACP threatens to sue Elon Musk’s xAI over pollution in Mississippi - February 13, 2026

- School consolidation bill dies without a vote in Mississippi Senate - February 13, 2026