A high-ranking lawmaker is asking Mississippi to use $5 million of opioid settlement money to explore the medical potential of ibogaine, a drug with mixed evidence of its ability to safely treat addiction.

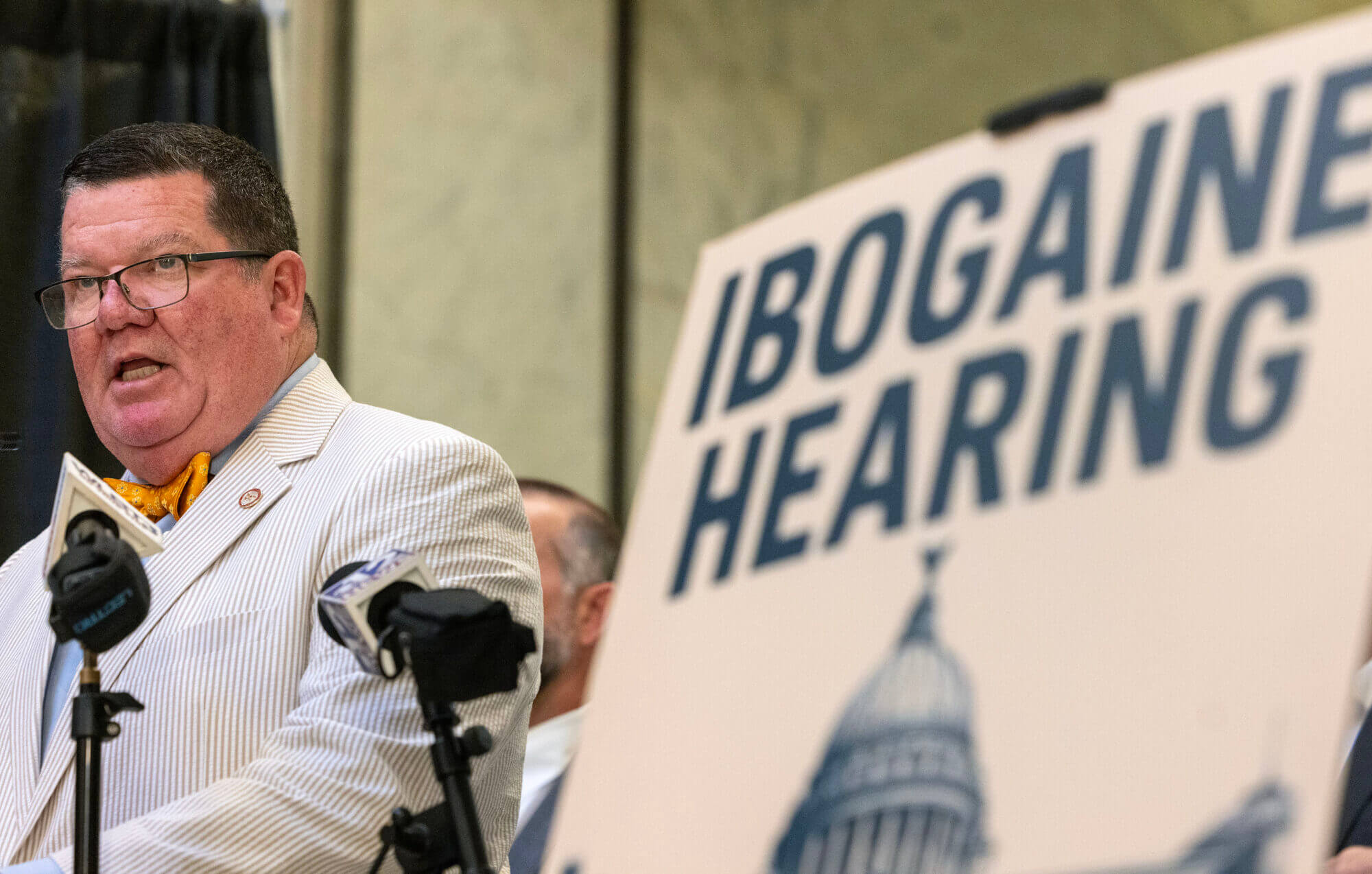

At a meeting Thursday of the House and Senate committees that deal with public health, Republican Rep. Sam Creekmore of New Albany invited testimony from speakers who support the use of the chemical for treating post traumatic stress disorder, traumatic brain injury and opioid addiction. Creekmore, who chairs the House Public Health and Human Services Committee, said Mississippi could prevent suicides and drug overdoses by investing in clinical trials that study the drug.

“We cannot keep using the same conventional methods for these ailments and expect different results,” he said.

Some studies suggest ibogaine, a molecule found in a shrub native to West Africa, can help treat substance use disorder. But analyses of these research papers have pointed out that most of the evidence comes from studies with few people and no comparison group.

A review conducted by researchers across North American universities in March found that most examinations into psychedelics, including ibogaine, and their ability to treat opioid addiction were “found to have high risk of bias” because of their study designs. It said there were possible ibogaine deaths in two of the studies.

While many mental health conditions do not have clear treatments, the FDA has approved medications that effectively treat opioid use disorder. Addiction researchers across the country call two of them, buprenorphine and methadone, the “gold standard” for treating opioid addiction.

Ibogaine has been linked to dangerous heart problems, particularly cardiac arrhythmias. Brian Shoichet, the University of California San Francisco Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry chair and a psychedelic researcher, told Mississippi Today in an email that while making access to ibogaine easier may help a lot of people with mental illness, it could also lead to more deaths.

“There are alternatives to ibogaine, often having the same mechanism of action but without the arrhythmias, that will be safer and perhaps just as efficacious,” he said.

It’s uncommon for any state to fund clinical trials. Studies for many treatments for mental illness are funded by private investors or branches of the National Institutes of Health. But over the past few years, some states have proposed using public dollars to fund experiments on the drug. Last spring, Texas set aside $50 million and Arizona allocated $5 million for ibogaine clinical trials.

Five speakers, including three Mississippi military veterans, shared personal stories about traveling outside the U.S. to receive ibogaine treatments for mental disorders. All praised the drug’s impact on their lives and encouraged lawmakers to fund ibogaine clinical trials.

“My migraines vanished, my chronic depression was dramatically alleviated,” Myles Grantham, a Mississippian who served in the Army, told the committee. “For the first time in years, I felt a shift.”

Bryan Hubbard, chief executive officer of the nonprofit Americans for Ibogaine and a speaker at the hearing, has traveled to states across the country encouraging lawmakers to invest in Ibogaine research. He told Mississippi Today the drug’s dangerous side effects can be mitigated under proper medical administration, and some Mississippians with mental health disorders could join the experiments as participants if the state provides money for the trials.

Hubbard said ibogaine drug development is expected to cost $300 million to $350 million, and he hopes trials could lead to a Food and Drug Administration approval of ibogaine as a medication within six years. He criticized existing addiction medications like buprenorphine and methadone, saying the crisis has persisted even with these treatments available.

“We are here to introduce an additional therapeutic option through a fractional amount of money that is used on what we have just for a potential breakthrough,” Hubbard said.

Dr. Benjamin Howell, a faculty member of the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, said in May that while buprenorphine and methadone aren’t perfect, they’ve been proven over decades to treat opioid addiction well.

He said one of the biggest reasons tens of thousands of Americans continue to die of overdoses is because they can’t get these treatments.

“I’m open minded that there might be future treatments that could be developed that are superior,” he said. “And yet, we also don’t have systems that are allowing everyone to get access to the medications that we know work.”

Most of the money Mississippi has received from the opioid lawsuits – cases that accused pharmaceutical companies of marketing and distributing prescription painkillers in a way that led to hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths – is controlled by state lawmakers.

Unlike most states, the Legislature and Attorney General Lynn Fitch have set aside some funds to be spent on purposes other than addressing addiction and have yet to spend any of the state government’s share on curtailing the public crisis.

Creekmore told Mississippi Today he would like the Legislature to use millions of dollars from the general purposes settlement pot to financially support pharmaceutical companies that could run ibogaine clinical trials.

“We could pave a road with it,” he said. “But I think it needs to go toward opioid abatement.”

Nine out of 10 drug clinical trials fail to receive FDA approval, but Creekmore said he believes the risk of not funding ibogaine research outweighs the risk of Mississippi’s settlement money not leading to a new medication.

He pointed to some of the public speakers’ stories of ibogaine treatment as evidence that the experiments are worth pursuing.

“It’s obviously working or they wouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

Ibogaine is a Schedule 1 drug on the U.S. list of controlled substances, meaning the federal government believes the compound is dangerous and has no medical use. The scheduling system has been criticized by many public health researchers who say it can prevent research into potential medications.

Mississippi Department of Mental Health Medical Director Dr. Thomas Recore gave the health committees an overview of the potential of psychedelic drugs, including ibogaine, to treat mental health conditions. He told lawmakers that as they think about whether to invest in ibogaine trials, they should consider whether it has enough potential to merit further study rather than whether it’s a cure-all for all mental afflictions.

“The answer for me is a clear yes,” he said.

Creekmore has been writing opinion pieces promoting ibogaine’s potential therapeutic uses throughout the summer. He frequently cites a 2024 Stanford University study in which researchers reported that among 30 veterans with mild traumatic brain injuries, many had decreased PTSD, depression and anxiety treatments a month after receiving ibogaine treatment.

The scientists did not report any adverse cardiac effects in the study, which they said could be because the veterans received magnesium simultaneously.

Creekmore and Recore were two attendees of dozens for a conference Hubbard organized last spring called the Aspen Ibogaine Meeting. Its website says the group hosted lawmakers from as many as 17 different states.

Robert Gulock, the meeting’s coordinator and a private medical consultant, told Mississippi Today in May that Creekmore and the other legislators paid for their flights and lodging themselves. Creekmore and Hubbard said they do not have financial ties to the development of ibogaine as a medication.

Howell, the Yale physician, said he believes the public health priority for preventing more overdose deaths should be connecting people who need it with tools already proven to be effective, rather than a compound that could take years to move through the FDA approval process and may not lead to any new medication.

“The history of medicine is littered with things that didn’t work out,” he said.