Charlie Riedel / Associated Press / File

Well into the pandemic, Jackie Courson’s doctor wanted to set up a telehealth appointment. Courson was skeptical. He’s on a costly satellite internet plan with a company headquartered in Maryland whose service he can’t exactly rely on.

“Look, we’ll try,” Courson said to his doctor. Then as he predicted, a video conference just wasn’t possible.

“It just wouldn’t connect. It’d spin and it’d buffer and whatnot, so we just ended up talking (over the phone). I didn’t get seen but I got heard,” Courson said.

Courson, who lives just outside of the city of Pontotoc, gets his electricity through Pontotoc Electric Power Association (PEPA). PEPA is an electrical cooperative serving Pontotoc and Calhoun counties that was formed like many others in the 1930s to bring electricity to the most rural areas of the country.

Cooperatives are mutually owned by everyone who is a member. Members elect board members to elect their interests, like providing broadband, while taking into account traditional business calculations like profit margin. In contrast, private providers like Entergy or AT&T are privately owned companies that make decisions solely based off traditional business calculations.

He and many others in his community assumed that after the Legislature allowed cooperatives to start providing broadband in 2019, PEPA would start laying the groundwork to do that, like other surrounding cooperatives did.

As the year went on, though, “members began to see that our board was not real enthusiastic about getting in the broadband business because they had been debt free for many years. There’s nothing wrong with fiscal responsibility, but all of a sudden we woke up and saw that all of these EPAs around us had already voted to do it,” Courson said.

Until the pandemic hit, members began packing out PEPA board meetings, with over 600 people in attendance, Courson said. They started a Facebook group advocating for broadband that now has almost 3,000 members.

But still, PEPA did not opt to start providing broadband, citing that it was not economically feasible to do so. The co-op also didn’t apply for state or federal grants available through Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act funds that would have helped pay for the creation of a broadband operation there, said Brandon Presley, Public Service Commissioner for the Northern District of Mississippi.

“Frustrated and highly disappointed would be a good way to describe it,” said Courson on the way his community feels about the cooperative’s broadband efforts, or lack thereof.

So now, when school, work, doctors visits and so many other aspects of life have moved online, roughly 40% of Pontotoc County and 20% of Calhoun County do not have access to high speed broadband internet, according to Broadband Now, a national database that tracks broadband access across the country.

That’s why Courson ran to be a PEPA board member — one of nine people who make decisions on behalf of everyone the co-op serves. On Thursday, Courson beat his opponent and will assume office Jan. 1.

“What you’ve got going on in Pontotoc right now is a very contested election for the board of directors where candidates are running on defeating (incumbent) board members because of their opposition to bringing broadband. So the people are going to have their say one way or another,” Presley said in an interview with Mississippi Today earlier this year.

A message left requesting an interview with a PEPA representative was not returned to Mississippi Today.

Pontotoc and Calhoun counties are unique in that their cooperative isn’t working toward providing broadband. They’re in the same boat as thousands of other Mississippians — especially rural ones — who don’t have access to affordable, reliable broadband.

People often discuss the gaping digital divide, but what’s not talked about as much is the reasons why one exists at all. It’s a quieter, more convoluted story, albeit one with massive consequences.

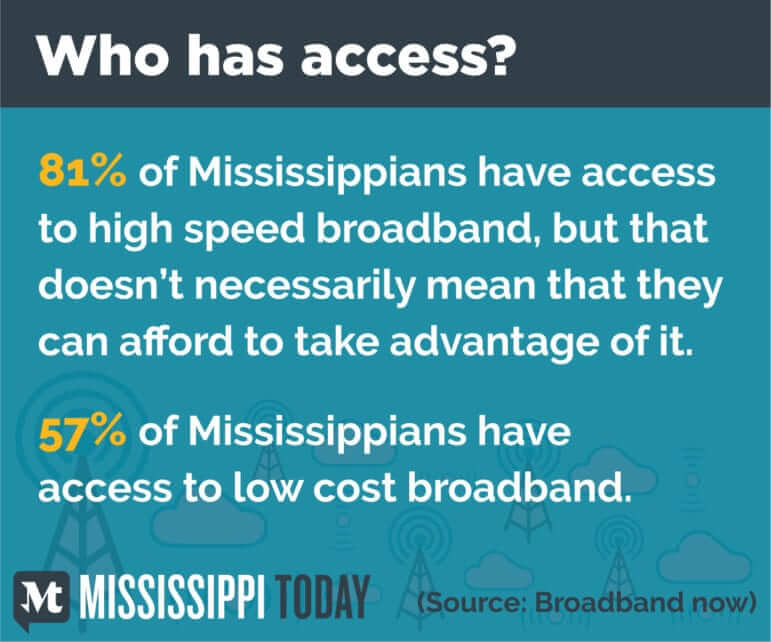

In Mississippi, 81% of people have access to high speed broadband internet, meaning there is a broadband provider in their area from which they could technically purchase internet service. That doesn’t mean that 81% of Mississippians actually have a broadband subscription, it just means that 81% could, if they could afford it. According to Broadband Now, 57% of Mississippians have access to affordable broadband.

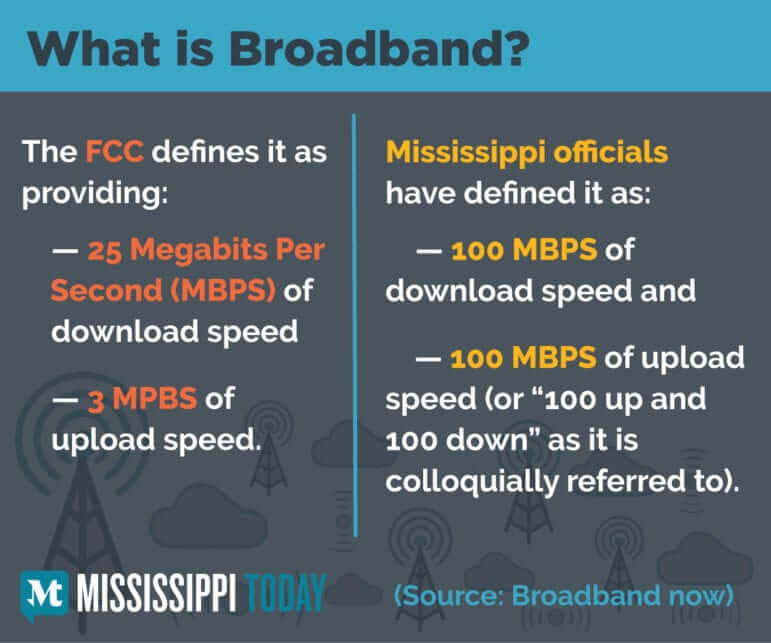

The state and federal definitions vary on what exactly broadband internet is, but it essentially boils down to how quickly something can be uploaded or downloaded.

To Presley, the reasons for the digital divide are complicated but hinge on a few core concepts.

“Policy in the state of Mississippi has not made broadband a priority prior to 2019. It’s just that simple. It was not a priority. It was viewed as cotton candy at the county fair. They might want, but they may not need,” Presley said.

Along with prior apathy among policy makers, Presley also points to private broadband providers who haven’t expanded their efforts to the most rural parts of Mississippi because they couldn’t earn a profit by doing that.

“What really is the culprit, in my opinion, has been the idea that the market will just simply handle the need for broadband. ‘We’ll leave it up to the market. The market will handle it.’ The market has failed — and it’s not even a close case — the market has failed rural Mississippi,” Presley said.

This meant that people living in rural areas were at the mercy of private providers to decide if it was profitable to provide broadband in that area, and it usually isn’t because not enough people live there who would pay for the service. If a company deemed it couldn’t make enough money by laying fiber in a rural area, then that area would continue to not have internet.

That was why Presley spearheaded the Broadband Enabling Act of 2019, which allowed electrical cooperatives to provide broadband to the most rural Mississippians. Before that law passed, the cooperatives were only allowed to provide electricity; it was not legal for them to provide broadband.

Private citizens have looked into paying themselves for broadband providers to lay cable near their house, but the upfront cost can be anywhere from $20,000 to $40,000, Presley said.

“Rural Mississippi has been told by internet providers that if they would just pay $30,000 for the polls and the lines, they’ll be glad to bring them $65 a month internet service. Well that’s ridiculous. Nobody is going to pay for that,” Presley said.

It was also the same problem rural America faced in the 1930s with electricity that led to the creation of electrical cooperatives.

“The Broadband Enabling Act of 2019 really was the door opener to fix the problem that persisted out there, because it’s absolutely no different than what it was in the ‘30s with electricity. Everyone needed it. No one could individually pay to get themselves service and we had to have a universal approach to service,” Presley said.

While the Broadband Enabling Act cleared the way for cooperatives to provide broadband internet, making that financially happen for some co-ops has, again, been complicated.

When it comes to providing broadband, the state’s electric cooperatives can generally be divided into two groups: “The ones that can economically get there, and the ones who are trying to figure it out,” said Executive Vice President and CEO of Electric Cooperatives of Mississippi Michael Callahan.

The cooperatives that have been able to make it work so far are generally smaller ones with denser populations, Callahan said. That means the cooperatives don’t have to pay as much to lay fiber per mile because there are fewer miles to cover and more people living per mile who are more likely to opt in and pay for the service.

The cooperatives that cover larger, less densely populated areas don’t have that benefit.

“For most of the studies that I’ve looked at personally, you’re looking at needing 12 to 16 customers taking your service per line mile (to break even). Across the state, our average meters per line mile is about 8.8. When you get up into the Mississippi Delta in some places it’s 2 to 4. I’ve got to be honest, it’s going to be tough to make this work in some of these places in Mississippi because the population isn’t there to sustain it,” Callahan said.

Callahan also said that some of these studies indicated that if there were only two households per line mile in a certain area who chose to opt in to broadband services they’d have to pay about $95 a month for the co-op to break even.

“One part of this Broadband Enabling Act is if we were to go into the business then we have to have a plan to provide broadband to every member of Twin County. So we have some areas that would mean running fiber several miles to offer it to one account and that account may not opt in,” said Tim Perkins, General Manager of Twin County Electric Power Association.

Aside from small parts of some neighboring counties, Twin County EPA mainly services Issaquena, Humphreys, Sharkey and Washington, which are some of the least connected counties in the state, though Twin County has recently started taking steps toward providing broadband.

Before COVID-19, the main ways that electrical cooperatives could cover the start up costs for entering the broadband business would be by taking out a loan, securing a grant, or using savings from the electrical business profits to invest in creating its broadband operations.

The law expressly forbade co-ops from raising residents’ electricity bills to help pay for broadband expansion in their districts.

For some co-ops, taking out a multimillion dollar loan to build out a fiber broadband network that people may or may not sign up for felt like too big of a risk, said Brent Bailey, Public Service Commissioner for the Central District of Mississippi.

In essence, the economic reasons that kept private providers from bringing broadband to rural Mississippi were the same reasons that cooperatives gave for deciding not to get into the broadband business.

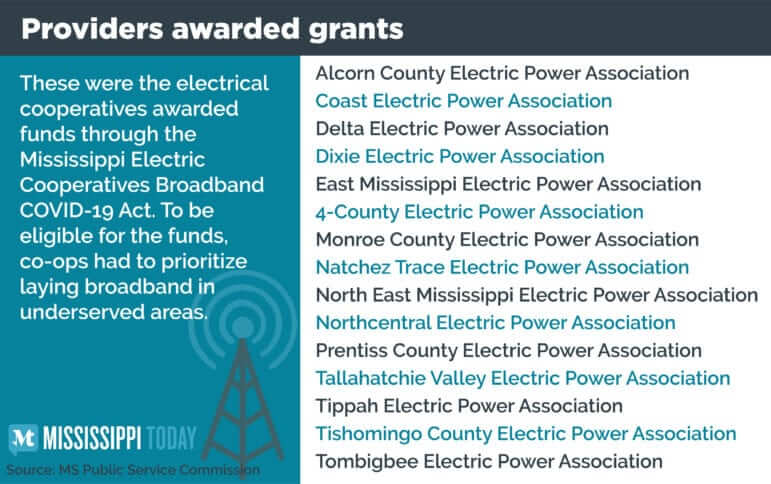

But since the pandemic, millions of dollars in grant money have been made available by both state and federal agencies. Out of Mississippi’s 26 electric cooperatives, 15 received CARES money allocated through the state to expand their broadband operations. Mississippi Electric Cooperatives also stand to gain $940 million phased in over 10 years through the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, which is administered through the FCC.

Back in Pontotoc and Calhoun counties, three out of the nine PEPA board member seats were up for election. Two were contested and one was a race between two people who would be newcomers to the board. While Courson won his seat, an incumbent board member beat a challenger who was campaigning on broadband expansion. Robert Tedford won the other seat. He did not want to comment on whether he’ll advocate for broadband expansion when reached by Mississippi Today. This makes Courson the sole board member who is publicly pushing for broadband in his community. And at this point, PEPA has already lost out on millions of dollars it could have received in state and federal funding.

Still, Courson remains optimistic. He hopes that by joining the board he can at least try to persuade other board members to start providing broadband to the community.

At this point, Courson said, that’s just about the only option they have.

The post Mississippi is one of the most under-connected states in America. Why is that? appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- State Supreme Court considers reviving former Gov. Phil Bryant’s lawsuit against Mississippi Today over welfare scandal coverage - February 18, 2026

- Winter storm update: Mississippi still waiting on fed declaration for individual assistance, lawmakers crafting plan to fund recovery - February 18, 2026

- Shy of special session, Mississippi school choice appears dead - February 18, 2026