by Samuel Hughes with contributions from Aidan Tarrant and Pragesh Adhikari

POPLARVILLE – From cinderblock, single-story duplexes and quadplexes to rows of brick townhomes, public housing projects aren’t difficult to spot in Mississippi — particularly those that buckle under the weight of their age.

Getting these properties cleaned up comes with much federal red tape and frustration for many local leaders. As these past housing solutions go offline, underfunded authorities hope to address community needs by doing more with less.

Hurdles in public housing redevelopment

One abandoned public housing project in Poplarville, Glenwild, was built in 1967 with asbestos and lead paint and now sits vacant. The city has little power to address its condition.

“We would love to be able to just come in, demolish it and do something, but it’s not that easy,” said the Rev. Jimmy Richardson, a director for South Mississippi Housing Development. “There’s so much red tape … let alone the dollar amount it would take.”

Federal law requires a replacement plan before redevelopment. Glenwild’s cost estimate is around $10 million, and even if a project is planned, the South Mississippi Housing Authority must prove it has the financial backing to proceed.

Funding shortages and policy shifts

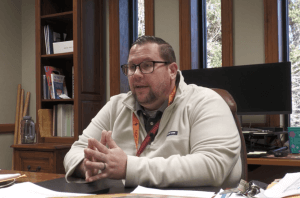

Public housing authorities nationwide have struggled with budget shortfalls for decades. Justin “Jimmy” Brooks, president of the South Mississippi Housing Authority, said funding has been insufficient since the 1980s.

“When I was a director at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in in the 2010 time period, we estimated there was about a $40 billion shortfall in what we needed to take care of our priorities nationwide, and that was in 2010 — it’s probably more than tripled since then,” Brooks said.

To offset this shortfall, HUD introduced the Rental Assistance Demonstration program, shifting public housing to a private funding model with capped rents.

“A lot of large housing authorities — us, included — just dove right in. We took all of our public housing out of the public housing program — put it all this private program. It’s been an absolute challenge ever since, because we don’t generate enough revenue to take care of the properties, and now we’ve eliminated our ability to get federal grant funding,” Brooks said.

Now, the South Mississippi Housing Authority must generate its own revenue, much of it from capped rents. In some cases, rent prices are set at half the market rate.

“For example, a two-bedroom rent here, the market rent is $1,000 — we might be getting $540 a month. We’re literally being asked to do the same thing as the private market, with substantially less funding,” Brooks said. “We’re stuck with it until Congress takes action, which is to be determined.”

Rising costs and insurance pressures

Brooks said the biggest challenge for Mississippi public housing has been rising insurance costs, which have been eating away at the authority’s operational budget.

“When I came here (in June 2021), it cost about $1.2 million to insure all of our properties. Now, the cost to insure our real estate is over $4 million,” Brooks said. “We’re scared to death to see what our May 1 renewal is going to look like this year, but whatever it is, the properties can’t afford it today, and we could barely afford what the insurance was last year.”

The South Mississippi Housing Authority, the largest in the state, serves about 26,000 people. It manages 917 active units and about 100 deteriorating ones across Mississippi’s lower 14 counties. As costs rise, more units may go offline.

“We’ve got lagging income, we’ve got expenses that are just on a rocket ship ride. We’ve got insurance that is completely unaffordable to anyone in luxury apartments down to government-subsidized housing, and if you can get the materials that you need to maintain your properties, you’re going to pay probably 50% higher than what you could realistically budget for. And we’ve got all of those factors rolling into what is ultimately going to be the biggest crisis that I’ve seen in affordable housing,” Brooks said.

As a result, many of these public housing projects sit untouched, falling into further dilapidation.

“Which creates friction with cities, with counties, with code enforcement, with the community who’s saying, ‘Hey, you really need to do something about these properties,’ Brooks said. “And then you have public housing authorities like us that are saying, ‘Well, we’re already investing $2 million of losses back into to the properties to keep them at the status quo.’”

In Poplarville alone, the South Mississippi Housing Authority loses more than $100,000 annually to keep public housing units online for low-income families. In 2025, as the South Mississippi Housing Authority faces these pressures, more units will go offline, Brooks said.

For smaller properties like Glenwild, projected revenue from capped rents does not cover the costs of redevelopment. The South Mississippi Housing Authority has a plan to demolish the 12 units and partner with a nonprofit to build affordable single-family housing, a plan not yet approved by HUD.

Despite these challenges, housing authorities across Mississippi are still working to provide new public housing solutions. The South Mississippi Housing Authority is about to begin construction on a 40-unit project in north Gulfport called North Park Estates Phase 2, which involves demolishing old, dilapidated units for a rebuild.

“We’ve had supply issues. We’ve had construction pricing issues. You know, the 40 units, we estimated it would cost about ten million to build it. We’re up to about $14 million in estimated cost right now,” Brooks said.

Brooks said large projects are more cost-effective for public housing developers because they produce more revenue, but getting money on the front end is challenging. He said much funding for affordable housing at the city and county level has dried up in the past two decades.

The authority’s other active project, Coastal Pointe, includes more than 12 funding sources to form a $16 million plan viable to HUD. The project will demolish older units on a property called Canal Point and move residents into 60 units of new, three-story apartment buildings.

Sheleatha McCullum, 44, was born and raised in Gulfport public housing. Currently a nursing assistant, she said her six years at Canal Point has allowed her to achieve some financial stability is looking forward to the new project.

“(Public housing) has helped me tremendously in trying to get to where I’m trying to get to,” McCullum said. “I don’t plan on moving, but if I did, this would be a start — for anybody.”

Tamillia Black, a Moss Point native, moved into Canal Point three years ago. She is thankful for what she finds to be a peaceful community.

“I was homeless. I had nothing. It’s a blessing to have a roof over my head,” Black said. “I was on a wait list; I think I waited five years to get out here. I was home to home, living off others. It was tough for me at some points, really tough.”

Black said public housing is necessary, and that new development at Coastal Pointe is necessary to answer the aging structures in the community.

State response and mitigation efforts

“With public housing, you face a dual problem, because public housing in Section 8 usually has rent limits as to what the federal government will let an owner of public housing charge, and it doesn’t accommodate any increase in insurance every year,” said Mike Chaney, Mississippi Commissioner of Insurance.

After Hurricane Katrina, the state Legislature formed the Comprehensive Hurricane Damage Mitigation Program, which provides grant funding to make properties, particularly those of lower-income individuals, less vulnerable to storm damage in the six coastal counties: Pearl River, Stone, George, Hancock, Harrison and Jackson counties.

Mississippi state law requires insurance companies to give discounts for homes mitigated to the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety FORTIFIED standard, which includes reinforced roofs and windows.

“If you mitigate a home or public housing or storm damage, you reduce the insurance rates anywhere from 30 to 40%, and that’s been our proactive choice,” Chaney said.

The program was unfunded until last year, when it received $5 million to provide $10,000 to each selected recipient to fortify buildings and to measure public interest in such a program.

House Bill 959, currently in the hands of the Senate, would extend the program. While Chaney hopes to see more funding appropriated to the program, he has not seen much interest in the state legislature.

Chaney also said the federal government is unlikely to help curb the impact of insurance rates on public housing anytime soon.

“I don’t see the government putting any money out at all to try to raise any of the rent subsidies that they give out for the cost of living, or the cost of insurance,” Chaney said.

U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, chair for the upper house’s Transportation, Housing and Urban Development subcommittee, did not respond to our request for comment on developments at the federal level.

As Mississippi housing authorities balance these increasing financial strains, Brooks said policy responses will have to be made at the state and federal levels to keep the state’s public housing at the status quo.

“This isn’t a Mississippi problem. It’s certainly not a Poplarville problem. It is a nationwide challenge that I would say is starting to get to crisis level,” Brooks said. “There are millions of units of public housing that are that are in this situation.”

The post Mississippi public housing struggles as federal funding falls short appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Scott Colom raised most money, but Cindy Hyde-Smith has most cash before March primary - February 21, 2026

- Patients face canceled surgeries and delayed care amid UMMC cyberattack - February 20, 2026

- Goal is ‘better alignment, not bigger government’ for Mississippi tourism - February 20, 2026