After being ambushed by a rival group, Prince Abdul Rahman Ibrahima went from being a Muslim prince and colonel in his father’s army to being enslaved in Mississippi.

Ibrahima spent 40 years enslaved on a Natchez plantation, far from his homeland in Futa Jallon, which is in present-day Guinea. Today, the city now has a historical marker honoring his story.

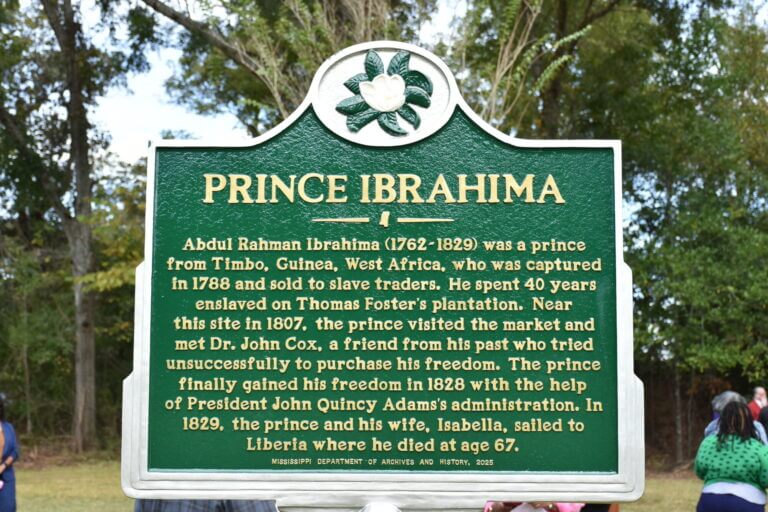

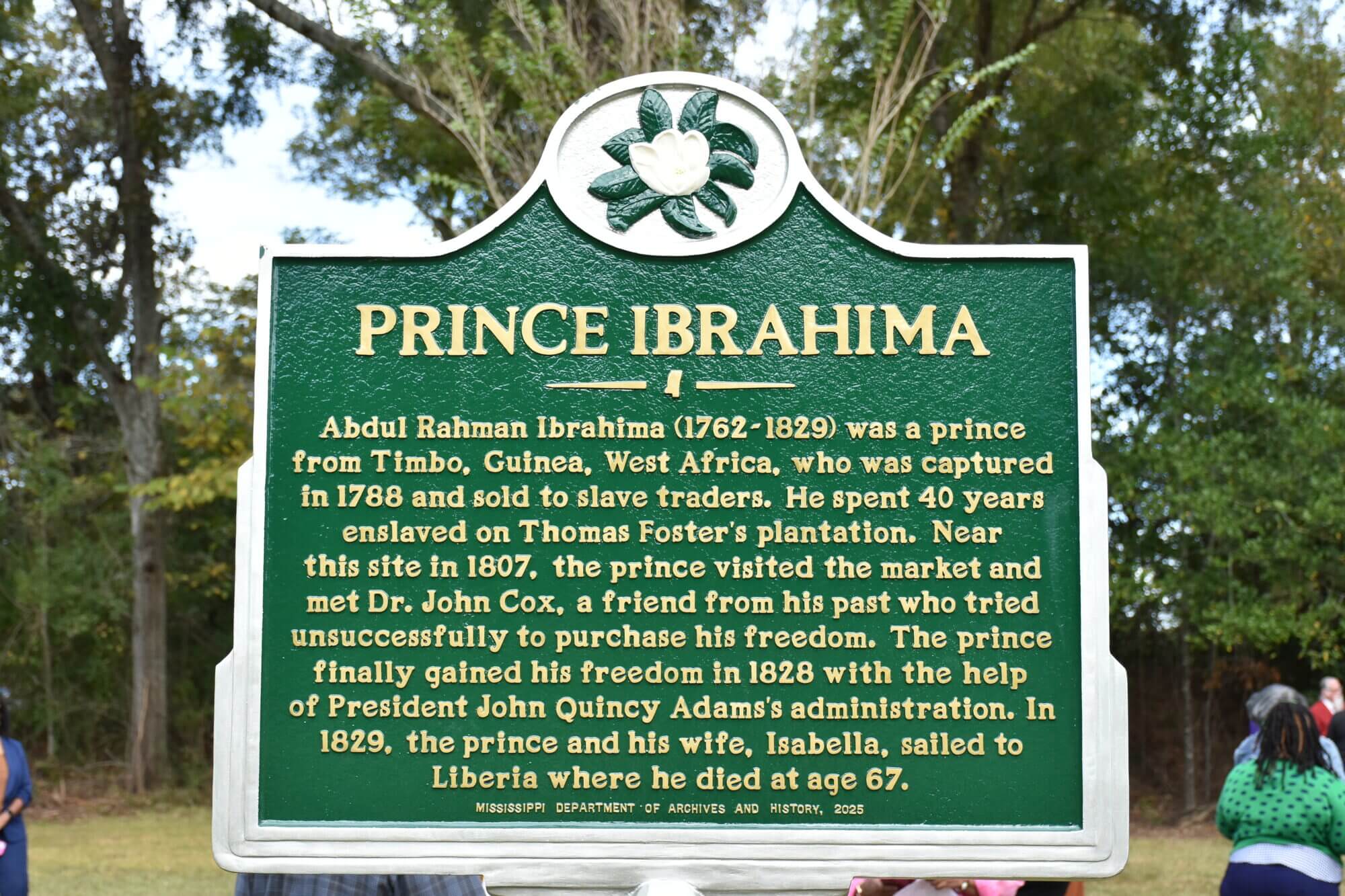

The marker, unveiled on Oct. 24, sits at the corner of Highway 61 North and Jefferson College Street, near Historic Jefferson College. The Natchez Historical Society approved a donation to buy the marker from the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Roscoe Barnes III, president of the historical society and the Cultural Heritage & Tourism Manager at Visit Natchez, told Mississippi Today about the significance of Ibrahima’s story.

“We believed it was time to honor his life and his legacy, to commemorate him for the time that he spent here and the story that he left behind,” Barnes said.

In 1788, the rival group ambushed Prince Ibrahima, who was serving as a colonel in his father’s army, and his men.

They sold him into slavery. He wound up in Natchez, where he spent the next 40 years as an overseer on Thomas Foster’s plantation. He had nine children with an enslaved woman, Isabella.

According to Barnes, the marker is erected at the spot where Ibrahima reunited with Dr. John Coates Cox in 1807. Cox was an Irish doctor who briefly stayed in Futa Jallon, where he met Ibrahima as a child. The pair met at a marketplace in a small community near Natchez. Cox and, later, his son tried unsuccessfully for 20 years to buy Ibrahima’s freedom.

It was Ibrahima’s friendship with newspaper publisher Andrew Marschalk that led him to freedom. Marschalk agreed to help him with a letter to Futa Jallon.

It took a few years, but Ibrahima wrote the letter and gave it to Marschalk in 1826. Marschalk sent it with a cover letter to U.S. Sen. Thomas Buck Reed, who sent it to Washington, D.C. From there, it reached the sultan of Morocco who offered to pay for his freedom. Marschalk believed Ibrahima was a Moor from Morocco, and Ibrahima did not correct him.

President John Quincy Adams and U.S. Secretary of State Henry Clay helped negotiate a deal with Foster and the sultan to sell Ibrahima. The deal required Ibrahima to return to Africa. Foster also agreed to sell Ibrahima’s wife, Isabella.

Before leaving the country, the couple traveled to Washington, where Ibrahima worked with government officials and the American Colonization Society to raise money to free his children.

Ibrahima and Isabella made it to Liberia in 1866, sponsored by the American Colonization Society. However, Ibrahima became sick and died shortly after arriving of an unrecorded illness. Two of his sons arrived in Liberia the next year, one with his own wife and children. Ibrahima never returned to his homeland.

Barnes described Ibrahima’s story as “one of the most remarkable stories to come out of this area”. Historian and author Terry Alford retold his story in “Prince Among Slaves: The True Story of an African Prince Sold into Slavery in the American South.” That book became the basis for the PBS historical drama “Prince Among Slaves.”

Barnes explained that Ibrahima’s story is a view of slavery in Africa, the United States and southwest Mississippi.

“It is a story about darkness, a story about pain, suffering, enslavement, but that’s not all. It is a story about hope,” he said.

- Ole Miss QB Trinidad Chambliss’ NCAA appeal is denied, but legal fight over eligibility continues - February 5, 2026

- Visitor brochures are returned to Medgar Evers home - February 5, 2026

- Advocates demand fix for Mississippi’s child care crisis - February 5, 2026