FLOWOOD – On the eve of the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, members of the Mississippi Building Code Council sat befuddled inside a conference room a stone’s throw from the Jackson airport.

The council’s leaders agree Mississippi would benefit from a statewide, uniform building code – a policy experts widely believe improves an area’s chances of surviving destructive weather. By lowering risk, strengthening buildings also helps against rising insurance rates.

“It’s kind of like the three little pigs: You want the straw, the sticks or the brick?” said Jennifer Hall, vice president of the council. “I want the brick.”

But the Legislature, the council also agreed, has no interest in expanding regulations. If anything, lawmakers are more interested in weakening what rules are in place.

“There is a movement at the Capitol right now to do away with regulations,” Hall said at the meeting.

After seeing the impact Katrina had on weaker homes and businesses in 2005, lawmakers in 2014 passed a statewide building code, requiring construction to meet modern standards. But the 2014 law included a key caveat: Within four months of the new regulation going into effect, any city or county could vote to opt out. As it turned out, most did just that.

Resilience experts, public officials and coastal residents who talked to Mississippi Today pointed to crucial policies to enhance local fortitude against future disasters: funding for mitigation and strong building codes. Yet while research suggests Mississippi is as vulnerable to climate change as anywhere in the country, state leadership has failed to embrace either strategy over the last two decades.

“Mississippi has had the opportunity to do this for years,” said Julie Shiyou-Woodard, president of Smart Home America and a Pass Christian native. “Sadly, it’s going to show. The choices we made in Mississippi after Katrina, you will see that when we get hit with a direct category 3 (hurricane) again. It will be clear.”

Train tracks in the Turkey Creek area of Gulfport, Miss., on Friday, Sept. 19, 2025. Credit: Eric Shelton/Mississippi Today

‘A silly question, Senator’

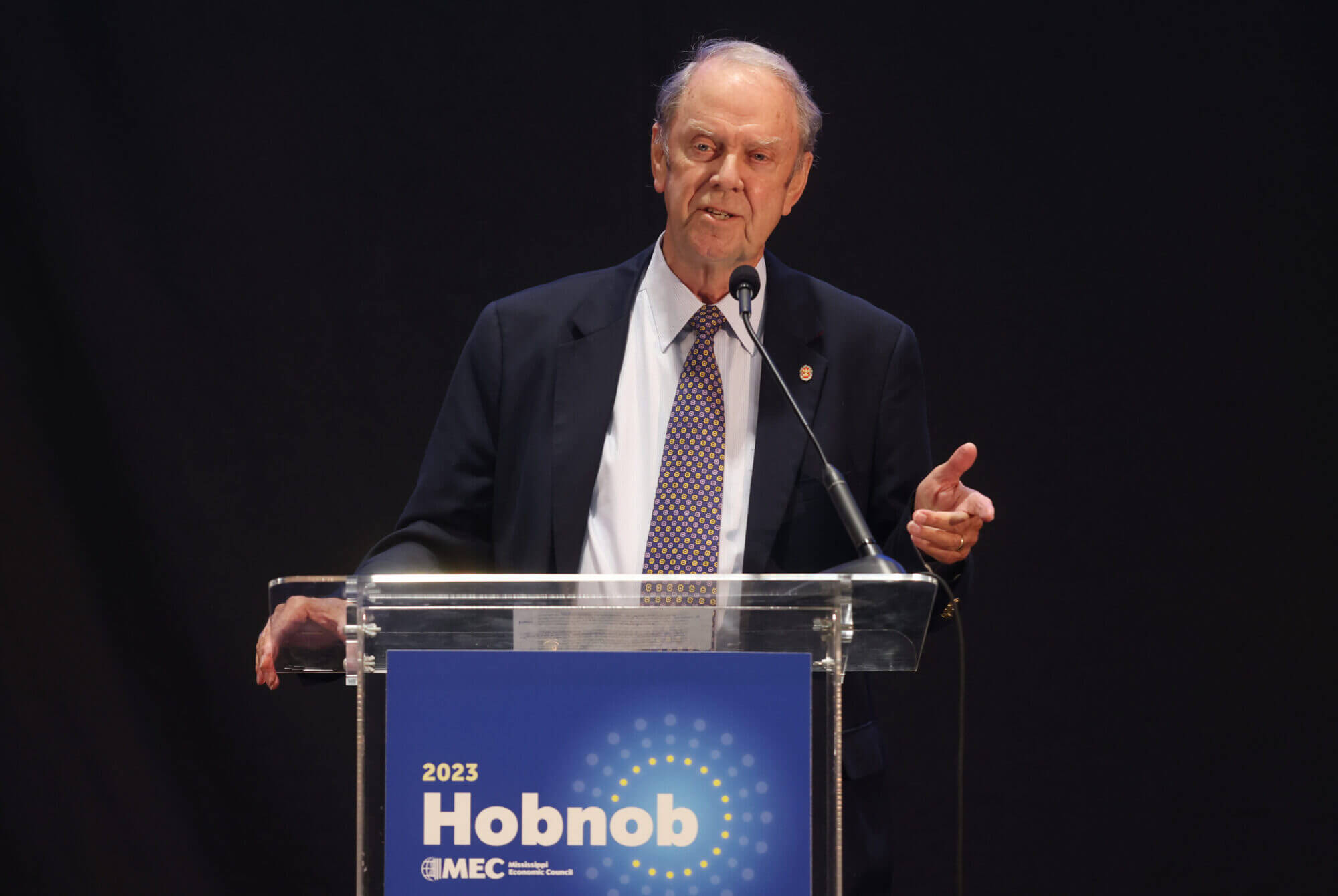

Mike Chaney, a Republican who has been the state’s insurance commissioner since early 2008, estimated that two-thirds of Mississippi’s counties opted out of the 2014 building code standards. Now, just about half of the state has “fairly decent” codes, Chaney said. The lower six counties– including three that touch the Coast – adopted codes shortly after Katrina, although most are now outdated, a federal database shows. The many places in the state without codes altogether are going to “hurt in the long run,” Chaney said.

Hall, who is also executive director of the Mississippi Manufactured Housing Association, said “the only way” lawmakers could have passed the 2014 bill was to allow cities and counties to opt out.

Mississippi Today reached out to several government agencies and organizations, and no one in the state, it appeared, tracked which areas have what building codes. The 2014 law gave no one the authority to actually enforce the codes it put into place, Hall said. In other words, there’s no accountability at the state level, even for the cities and counties that didn’t opt out in 2014.

Last year, the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety ranked Mississippi’s codes near the bottom among coastal states. The impact a lack of codes has on life-safety and property damage “has unfortunately been exposed in recent tornado outbreaks” in the state and “would be exploited in a hurricane impact,” the report said.

Over the last decade, tornadoes, strong winds and thunderstorms have directly killed 67 people in Mississippi, national storm data show. Also, including hurricanes, those storms have caused over $740 million in property damage in that time.

Disaster and insurance experts also point to mitigation grants as a necessary step toward local resilience. Alabama, Louisiana and other states have launched grant programs to help homeowners in high-risk areas pay for improvements that are often cost-prohibitive otherwise.

The Mississippi Insurance Department first established its home mitigation program in 2007, but it didn’t receive funding from the state until 2024 when lawmakers set aside $5 million for the department to do a test run.

With grants up to $10,000, the program paid to upgrade and strap roofs onto homes, protecting against high winds and water leaks. After slowly rolling out the program, which Chaney said was done to avoid mishaps, the state funded improvements to 28 homes.

In a dispute that played out in news stories and on social media over the summer, legislators were critical of the department’s ability to run the program. Particularly, Sen. Scott DeLano, a Biloxi Republican, said he disagreed with Chaney’s approach.

DeLano and other lawmakers slammed the Insurance Department for only doing 28 homes, said Chaney provided scant details about how the program would run, and argued the program should go through an independent contractor.

As a result, the Legislature omitted funding for the program this past session, and killed a bill that would have paid for the grants through fees from insurance companies. Republican Sen. Walter Michel of Ridgeland presented the bill on Chaney’s behalf.

Some of the criticisms about the pilot fell flat, Mississippi Today found. For instance, DeLano and others pointed to the success story in Alabama – which leads the nation with over 51,000 “FORTIFIED” homes – and said Mississippi should mimic its neighbor to the east. But the Alabama Department of Insurance told Mississippi Today that its program is run almost entirely in-house.

Chaney’s office pushed back on criticism over the results of its pilot program, arguing it executed more grants than other states in its first year.

At a Senate committee meeting in January, DeLano criticized Chaney, who was sitting a few feet away, for not also requiring counties to have up-to-date building codes before residents could receive a grant. Doing so would attract more insurance companies into the state, the senator said.

After Chaney said he would only support the idea in a separate bill, DeLano fired back:

“Are you really for mitigation then?”

“That’s a silly question, Senator,” Chaney responded.

Responding to Mississippi Today about the exchange, Chaney’s office said requiring a county to have certain building codes would only hold up mitigation progress.

The two elected officials agreed about the importance of a mitigation program, but each side accused the other of not playing ball. DeLano said Chaney hasn’t provided details of his proposal, and Chaney said DeLano wouldn’t meet with him to discuss the proposal.

Multiple people told Mississippi Today the distrust between the two sides traces back to 2016, when the state nearly lost $30 million in Federal Emergency Management Agency funds meant for retrofitting 2,000 homes on the Coast. An Office of Inspector General report recommended FEMA suspend the program after finding the state had spent over $30 million and did work on only 945 homes.

A levee can be seen near Turkey Creek in Gulfport, Miss., on Friday, Sept. 19, 2025. Credit: Eric Shelton/Mississippi Today

The Mississippi Emergency Management Agency fired the employees it claimed were responsible for the blunder. The agency eventually resumed the program and ended up with $19 million in federal funds, it told Mississippi Today.

But Rep. Kevin Ford, a Republican from Vicksburg, said lawmakers still have a “bad taste in their mouth.” When asked if the earlier scandal is why the Legislature hasn’t funded the program for roughly a decade, Ford said, “Yes, 100%. There’s no doubt.”

“What it sounds like to me is there is a trust issue,” said Chris Monforton, CEO of Habitat for Humanity of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, referencing the OIG report. Monforton, who worked with the insurance department to start its pilot program, said the pilot was “very similar” to how Alabama established its mitigation grants.

When asked about the issues from 2016, DeLano didn’t go so far as to tie it to his disagreement with Chaney, but said “we know the history of mitigation programs in our state.”

Ford, who wrote a competing mitigation bill in the House this past session, argued that Chaney as an elected official shouldn’t have control over the millions of dollars that would fund the program, suggesting the money could be tilted towards potential voters.

Chaney strongly disagreed with using an outside company to run the program, arguing a contractor would be more expensive and not subject to the same oversight as the insurance department. Both Ford and Michel said they would reintroduce their bills in the 2026 legislative session, and it’s unclear if either side is willing to compromise.

Rep. Jerry Turner, a Republican from Baldwyn, is the House Insurance Committee chairman and has served at the Capitol since 2004. When asked why it took 17 years for the state to fund a mitigation program, Turner said, “I’m not trying to dodge a bullet or pass a buck, but I think you’d be better served if you talked to the people on the Coast and the insurance (department).”

“I’m not siding either way,” he added. “ I’ll do anything I can to get this thing started off because I think it’s something that the citizens of the state of Mississippi deserve.”

‘The market will collapse’

The parallel rise of disaster risks and insurance costs in the nation’s poorest state begs the question: What will happen if neither trend slows down?

Chip Merlin, an attorney who specializes in insurance claims for homeowners and who worked with Mississippians after Katrina, said eventually communities will have to migrate.

“I think we’re starting to see it already,” Merlin said, pointing to parts of California and Florida that have seen residents leave because of climate risk. “There’s an emotional aspect of once your home gets damaged by flood, wind, wildfire, that I don’t want to be in harm’s way anymore. And people look for a place where it’s less emotionally taxing to live.”

David Baria, a Democratic former state lawmaker from the Coast, said he ran for office in 2007 largely because of the local issues with insurance he witnessed after Katrina.

Baria called it “a slog” to get any kind of insurance reform passed. He introduced bills in 2017, 2018 and 2019 to fund a mitigation grant program. None made it out of committee.

“ There were many bills that I attempted to pass to rein in insurance company practices to improve the lot of homeowners, to strengthen structures, and they were routinely opposed by the insurance industry and the leadership of both the Senate and the House,” said Baria, who served in both chambers.

Both Merlin and Baria criticized Mississippi leadership for not better protecting policyholders, especially around delaying or denying claims after a disaster.

In 2024, a New York Times analysis of an insurance study looked at which parts of the country pay the most in home policy premiums relative to their house’s value. The analysis found that, throughout Mississippi, that ratio was “much higher” than the national average.

Smart Home America, a nonprofit based in Mobile, Alabama, has helped strengthen homes and design policy in over 20 states. Shiyou-Woodard, its president and CEO, said she “worked closely” with Chaney’s office to kickstart Mississippi’s mitigation program, and it was on the right track until the Legislature cut its funding.

While policy around mitigation can face obstacles, such as building contractors not wanting to deal with the extra cost of complying with new codes, Mississippi’s lack of local resilience comes down to those in the Capitol, she said.

“Mississippi is a black hole,” Shiyou-Woodard said, explaining that its neighboring states are ahead of the game. “Why is it not catching up? There should be no reason. It has the same risk as Louisiana, the same risk as Alabama, what’s the problem? The problem in Mississippi has been political will.”

When asked what would happen if the state doesn’t act to lower the risk for homeowners, she pointed to Louisiana, which has only recently seen insurance improvements after a slew of companies pulled out due to frequent disasters.

“When Mississippi gets hit with a significant wind event, the market will most likely collapse,” she said. “And that’s not fortune telling. That’s just based on the market, and they’re not getting ahead of it.”

CORRECTION 10/20/25: This story was updated to reflect that the home mitigation program just paid for roofing.

- Former Greenwood police officer pleads guilty to federal drug trafficking charges - February 27, 2026

- UMMC officials say normal operations will resume Monday after cyberattack - February 27, 2026

- Hinds County public defender: Office needs additional funding to avert constitutional crisis - February 27, 2026