In the aftermath of a revolving door of presidents at Jackson State University, members of Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning board tasked with naming a new leader sought to defuse alumni concerns.

But after an hour-long Zoom meeting with dozens of JSU graduates last week, some alumni remained uneasy that the state’s college governing board would fall back on the same playbook.

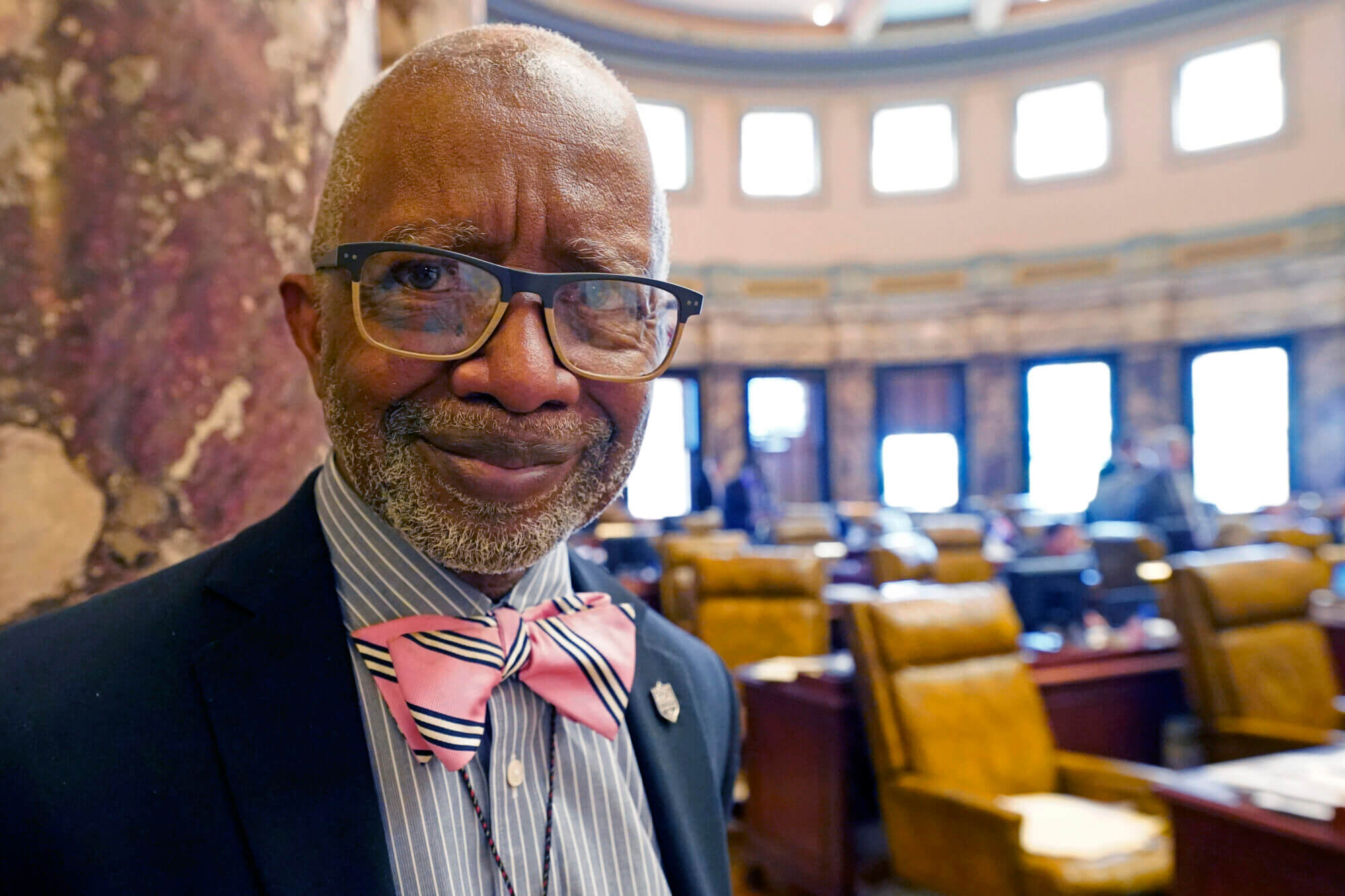

“Even Ray Charles can see the failures,” Sen. Hillman Frazier, D-Jackson, a member of the Universities and Colleges Committee, said. “They should be upfront on their intentions this time to have a fair and transparent search. They need to double down on their commitment to stabilize their credibility because it’s shot.”

The state’s largest historically Black university will be embarking on its fourth leadership search this fall after more than three president turnovers in less than seven years. The IHL board, which oversees and selects the school’s presidents, announced the resignation of Marcus Thompson in May.

No reason was given as to why he left his post as university president.

Jackson State University National Alumni Association invited some of its members to an exclusive, hour-long Zoom conversation with two IHL board members on July 7 to address concerns surrounding the university’s forthcoming presidential search.

Patrease Edwards, president of the national association, kicked off the conversation. Moderator Michael Jefferson, the group’s information, communications and technology chair, asked Steve Cunningham and Gee Ogletree a series of questions ranging from the college board’s vetting process to policies and procedures to ensure a fair and transparent search.

The roughly 71 alumni association members who signed up for the conversation submitted 52 questions. Nearly 14 of those questions, which were screened by the national alumni association, were directed to board members (There was no chat feature available.) It’s unclear how many of those who signed up attended the call. Edwards said students also joined the call.

In June, the national alumni association emailed its members inviting them to participate in the event. In the days leading up to the call, few details were shared. Alums who signed up to participate had questions about which IHL board members would be attending. Others said they didn’t know where to submit their questions. The link to the Zoom meeting was shared in an email from Edwards around noon on the day of the actual talk. Alums who said they signed up for the event said they didn’t get the email or missed it.

Cunningham, vice president of the IHL board, said he and Ogletree couldn’t answer specific or personal questions about past presidents because of confidentiality and legal personnel constraints.

He said a formal committee for the president search has not been named but that he anticipated more engagement with faculty, student groups and the alumni association during the board’s community listening sessions during the upcoming school year.

In past presidential searches for Jackson State, IHL launched a national search, opened an online survey and provided community listening sessions to help write a candidate profile, all first steps in the process. Ultimately, it will be the board that will make the choice for the school’s next president, he said.

“Of course it demands a delicate balance of transparency and solicitation of opinions and confidentiality for those going through the recruitment and interview process,” Cunningham said. “IHL board of trustees reaffirms its commitment to an open and engaged process.”

Criticism has dogged the board’s history of forgoing its own policies and appointing internal hires as top leaders, leading to protests, accusations of favoritism and bills to abolish the IHL board.

Thompson worked as deputy commissioner and chief administrative officer at IHL from 2009 before becoming president. He had no experience leading a university. His appointment as president was reminiscent of IHL’s decision to hire Glenn Boyce to head the University of Mississippi. Boyce had led IHL’s leadership search for Ole Miss. Both decisions eschewed search candidates in favor of an internal hire.

Board members were asked if Denise Jones Gregory, now the interim president, would get a fair shot for the permanent position. Gregory, a JSU alum, is a native of Columbus Mississippi, as is Cunningham.

Ogletree explained interim or acting presidents would have to step down to apply for the job if they wanted to apply for the role. However, if a number of supporters expressed their favor for Gregory as a top choice for leadership, the board could waive its policies to ensure she remains in the role. Olegtree said it’s too early to discuss how this process would go for Gregory.

“When we have found good, strong interims and when we hear from the various constituencies that they are the person that fits the criteria… then we haven’t hesitated to hire that person,” Ogletree said. “I will tell you Ole Miss is thrilled with Dr. Boyce now and Alcorn with Dr. Cook and we certainly have every expectation Jackson State is going to be thrilled with its next leader.”

Last year, IHL used this provision to appoint Tracy Cook, president of Alcorn State University, marking the board’s ninth time in 10 years it has hired an internal candidate as a top leader.

The board also suspended its search to hire Joe Paul, then the interim president at the University of Southern Mississippi, after he received support during the listening sessions. The appointment came with criticism from faculty and staff about the lack of transparency with IHL’s presidential search process.

Nora Miller served as Mississippi University for Women’s acting president, senior vice president for administration and chief financial officer before the board permanently appointed her the day of the listening sessions, another example of an internal hire by the board.

The biggest batch of questions alums submitted revolved around the board’s vetting process. Board members explained they obtain references and/or hire consulting firms to contact references.

They said the 12 trustees try to line up resumes and job requirements with the characteristics needed for president. They run background checks — inquiring about motor vehicles, criminal records and credit checks as well as internet and article information — but they’re not “foolproof.”

“It almost implies like we have some type of magic wand where we should be able to predict a human being’s behavior after they are appointed to a position of power, and we know that that is just impossible,” Cunningham said.

Ultimately, the board members said they will stick to its policies and “maybe make more calls this time.”

“We’re certainly aware of the need to do all that we can do,” Olegtree said.

Tim Rush, a 1986 JSU alum and former dean of students at Holmes Community College, said he appreciated the conversation but wanted to make it clear that all alumni do not share the same views and opinions as the national alumni association. He said IHL needs to truly listen to all stakeholders when making this next appointment.

“The best leaders will emerge from an open and transparent process that includes valued input from all stakeholders, and we will be able to support and rally around whoever that may be,” said Rush, a member of Thee 1877 Project, a small group of alums not affiliated with the national association who have been advocating for school issues around student housing, philanthropy and funding.

Mark Dawson, chairman of the 1877 project, said he felt the board members had an overall “cavalier” attitude when answering alumni questions, particularly whether they have learned lessons or will examine new approaches for their next search. Board members need to recognize their past failures have left a festering wound of trust for supporters of the university.

“Have you looked at what this turnover has done to enrollment, institutional giving, expansion of academic programs or our inability to move from an R2 to R1 research status?” Dawson asked. “Not examining the wrongdoings with this process has been damaging to your bottom line: students, faculty and community.”

Others question the impact of the board’s decisions on Jackson State University’s overall growth and economic impact on the state’s capital city.

. (AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis, File)

“In the end, the state is the one who is suffering to grow a really strong institution based in the state’s capital,” Frazier said. “Students want a viable option. They’re beginning to look elsewhere to fulfill their dreams. (The board’s) decisions have been costly. They need to follow their plans and don’t deviate from them. Stick with the game plan and don’t waste alums’ and taxpayers’ time this time around.”