President Donald Trump’s tax and spending bill, signed into law earlier this month, slashes social safety net programs that impact schools and children across the nation.

The ramifications could be particularly devastating in Mississippi, one of the most federally dependent states in the country.

The law limits eligibility for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, through which about a quarter of a million Mississippians with children receive food assistance. The policy also cuts the federal contribution to Medicaid, the country’s largest insurer of children, and creates a tax credit program that doles out private-school scholarships.

Here’s more about how the federal law will impact Mississippi students, teachers and families.

Tax credit private school voucher program

A new program created by the law will allow Mississippians to contribute up to $1,700 to an organization that awards scholarships to private school students starting in 2027, and donors will be given a break on their taxes equal to the amount they contribute.

It’s a dollar-for-dollar tax credit — about three times as much as people receive from donating to a children’s hospital or other causes.

The program is a huge win for school choice proponents in Mississippi — or “education freedom,” as House Speaker Jason White and others call it. He said the issue will be his top priority going into the 2026 legislative session.

But it’s a loss for the state’s public schools, said Nancy Loome, executive director of The Parents’ Campaign, a public education advocacy group.

“This is absolutely intended to shift public money into private schools,” she said. “This is the federal government reimbursing taxpayers for payments to private schools. It’s a kind of money laundering.”

Douglas Carswell, president of the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, calls that a “Pavlovian response” from school choice opponents.

“It’s not money that would have ever gone into the public education system in the first place,” he said. “It doesn’t apply because the dollars weren’t in the public school system to begin with.”

Loome said the program could also lead to private schools increasing tuition. It’s a risk that Carswell doesn’t deny, but says is unlikely given the eligibility criteria for the vouchers.

However, the eligibility criteria is generous — to qualify for vouchers, you can earn up to 300% of the area’s median income. That’s six-figures in Mississippi, or about $150,000, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

That’s in line with research that shows a majority of private school vouchers across the country go to students who could already afford and were attending private schools.

“It’s clear that these programs benefit wealthier, more affluent families,” Loome said. “Students in the public schools are the ones who will be left with fewer resources.”

The first step for implementing the optional program in Mississippi: The state must choose to participate. It’s likely, given powerful Republican state leaders’ support of school choice initiatives. Then, Carswell suspects we’ll see an increase in scholarship-granting organizations — the groups that will disburse these vouchers, whose sole purpose must be doing so. Ace Scholars is one such organization with an established presence in Mississippi, he said.

Mississippi currently only provides private school vouchers for students with disabilities.

“In Mississippi, we are finally getting to the place where we’re recognized for student achievement in our public schools,” Loome said. “It makes no sense for us to embrace a program that will take our students backwards.”

Federal money for workforce training

Another portion of the law in line with education movements in Mississippi: The ability to use federal grants to pay for short-term workforce training.

Low-income students who qualify for federal Pell Grants can use a Workforce Pell Grant on certain weeks-long training programs for skilled jobs starting next school year.

Scott Waller, president of the Mississippi Economic Council, said the change will have a positive impact in Mississippi, where state leaders have been advocating for more career and technical education opportunities for students. The push comes at a critical time, as Republican state leaders tout the state’s economic growth.

“Are you getting an education that’s tied to employment? That’s the key,” Waller said. “If that happens, it’s going to change the trajectory of a lot of lives in Mississippi.”

Education officials, too, have turned an eye to career and technical education starting in high school, so Waller said the timing of the federal Pell Grant changes couldn’t be better.

“The model we have right now is so geared to the academic side — not that that’s not important — but this is one more step to making connections between the needs of our students and the needs of our companies,” he said. “This is a step forward.”

Free school meals may be affected

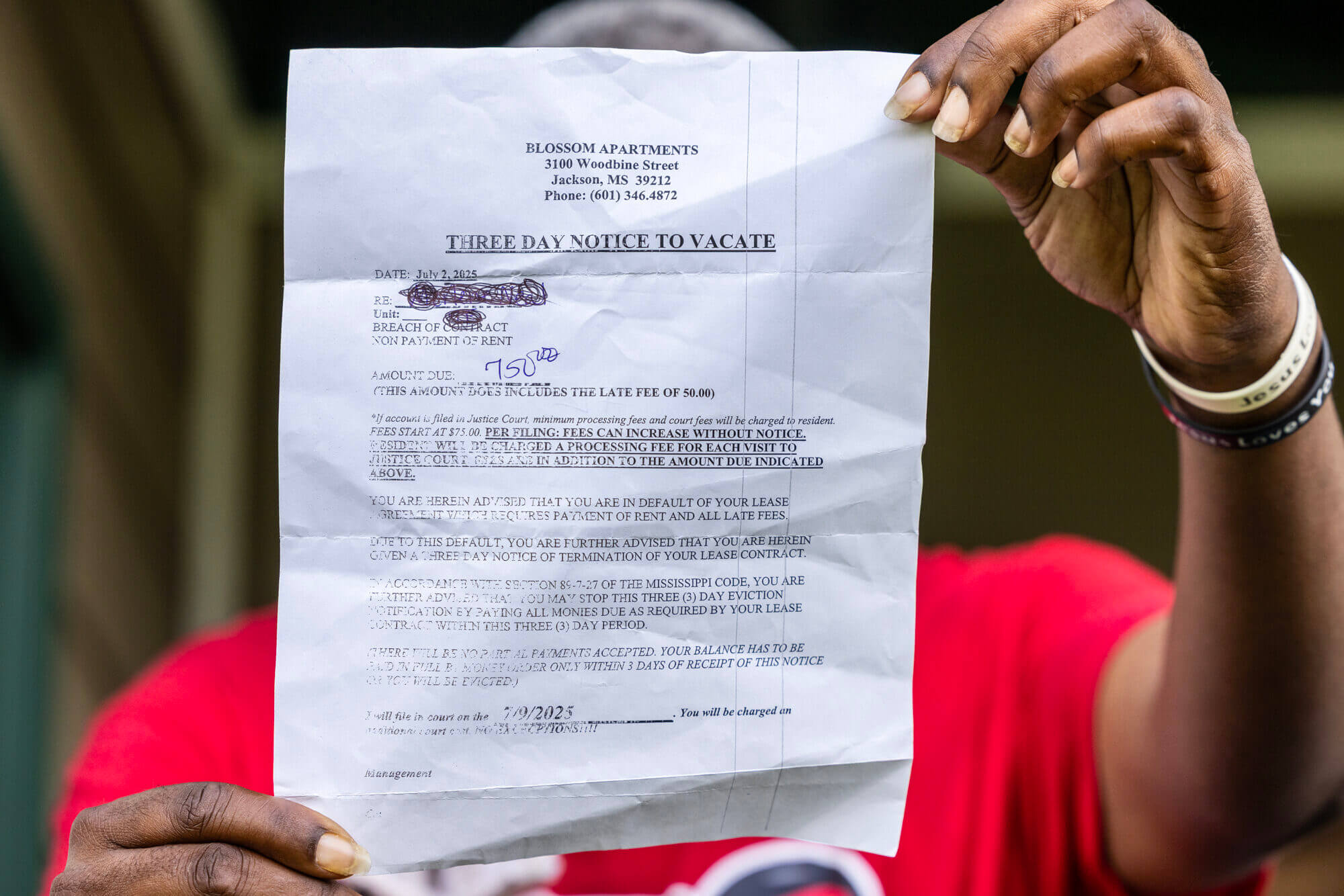

Trump’s legislation will create more work requirements for parents to qualify for the SNAP program, which may decrease the number of students getting free school meals.

That could have a domino effect on how many schools meet the federal threshold to provide free meals for all students.

While parents can still fill out paperwork at their child’s school for free meals if they are removed from SNAP rolls, it’s sometimes difficult to get them to do so, according to Amanda Williams, the incoming president for the Mississippi School Nutrition Association.

“We communicate and communicate, but it’s still hard to get parents to do it,” she said. “And if they have other things to pay for, like the light bill, they’re not going to think about sending a dollar with their child for lunch. We’re going to feed our babies anyway at the school, but those students will accumulate a bill that just gets higher and higher.”

Williams said she knows of schools in south Mississippi with upwards of $30,000 in school lunch debt.

About one in four children in Mississippi face food insecurity. And because the state is so rural, Williams said, there’s a greater burden on schools to feed children.

“Our students are not able to just walk down the street around the corner to a local restaurant or cafeteria or fast food,” she said. “If you have parents who work all day, the kid can get home and they’re still hungry. They will have to wait until their parents get home to eat.”

Hunger has a direct impact on student learning. Williams has seen it firsthand as assistant director of child nutrition at Meridian Public Schools.

“I mingle with students in the morning, and when they come in, you can look at their faces and see that they are hungry,” she said. “But once they come in, get their breakfast and start eating, their attitude changes.

“If our children aren’t eating, then they’re not going to excel in school like we want them to.”

According to health policy expert John Dillon Harris, who also studies nutrition, the state could be paying approximately $140 million more annually on SNAP, thanks to changes in the federal spending package.

The legislation makes states responsible for 75% of the administrative costs associated with SNAP instead of half, and the state could also be picking up millions in SNAP benefit costs.

Additionally, the law prohibits immigrants from receiving SNAP benefits unless they are classified as “lawful permanent residents.”

Ramped up immigration enforcement

Immigration enforcement is getting an influx of cash under the president’s spending legislation — an additional $31 billion for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and $13 billion for states and local communities.

If children’s families are affected by deportations or arrests, they may require more support in school.

ICE raids in 2017 and 2019 in Jackson left lasting trauma among students, teachers said, who required extra counseling at school.

“The students went home and their parents weren’t there, so the schools had to come to their aid,” said L. Patricia Ice, director of the Mississippi Immigrant Rights Alliance.

In the event of arrest, Ice encouraged parents to create family preparation plans — which include talking to children about who will care for them in parents’ absence, keeping contact information up-to-date in schools and designating a trusted individual as a guardian.

Medicaid spending on student services

While the federal spending law makes historic Medicaid cuts, experts say the direct impact on Mississippi schools is minimal because the state hasn’t expanded Medicaid.

In Mississippi, the state Medicaid agency pays for certain services in schools for students with disabilities, including speech, occupational and physical therapists, so those school-based services will not be impacted by the federal changes.

Federal funding to state Medicaid divisions will decrease under the legislation, though, so the Mississippi agency may make its own changes.