Market 105 @ 105 West College Street, Booneville, MS. Monday through Friday, 11:00am – 4:00pm.

Market 105 is located in the heart of historic Booneville, surrounded by quaint shops, historical buildings, and old town city sidewalks begging to be explored.

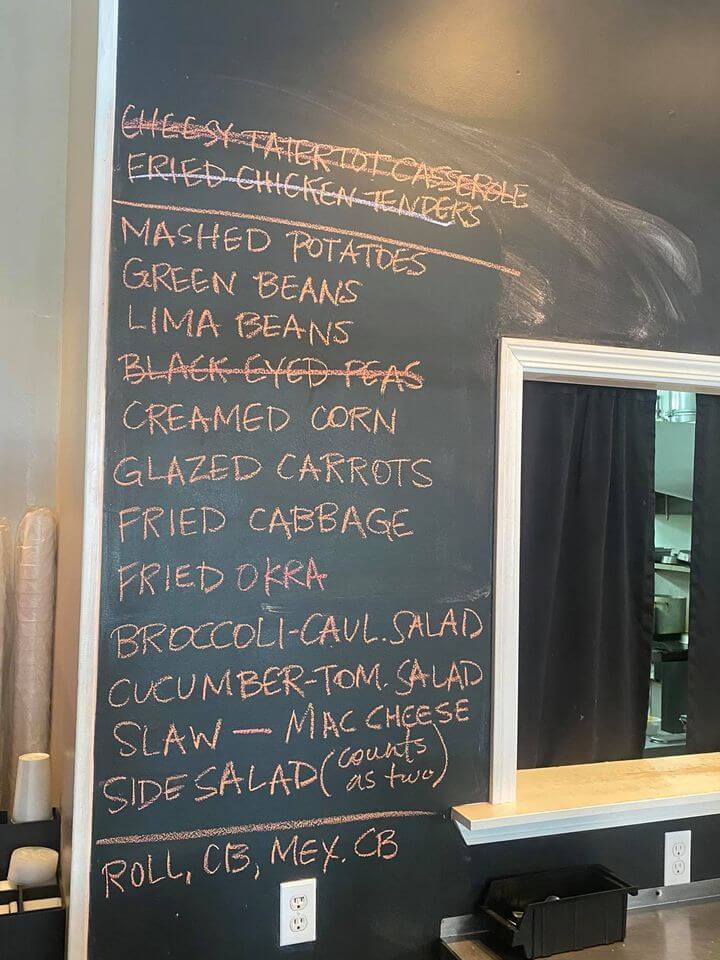

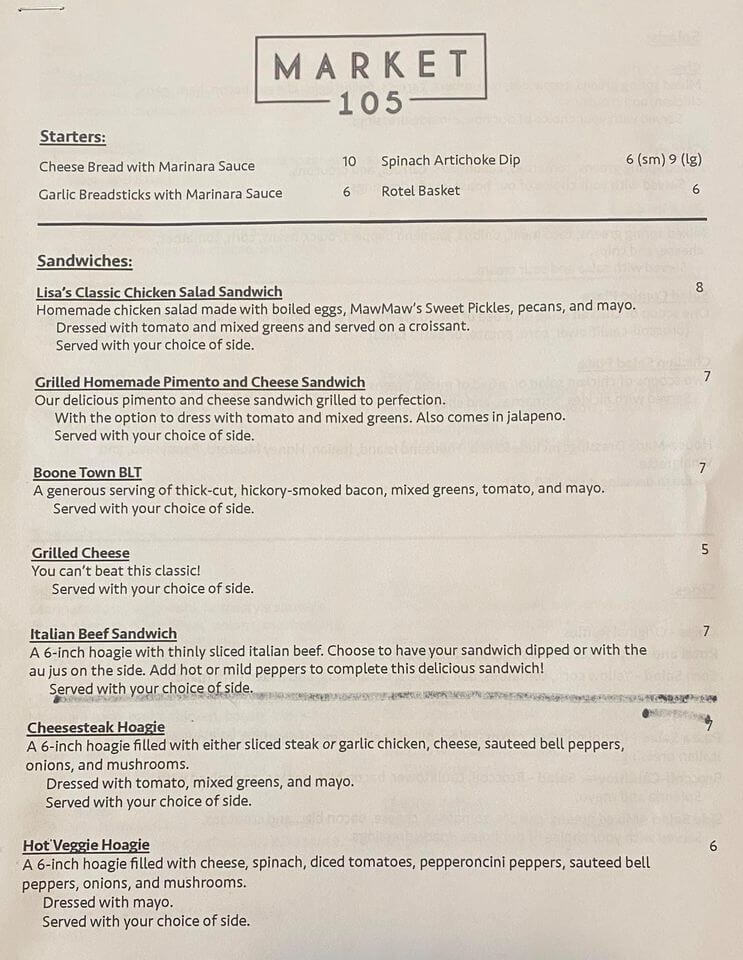

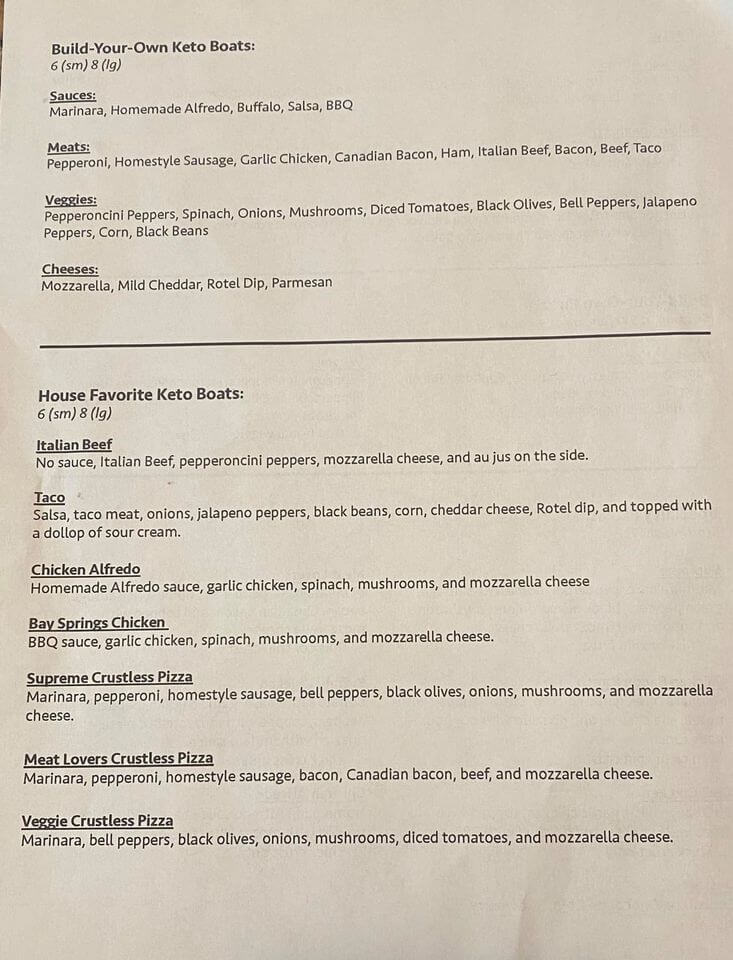

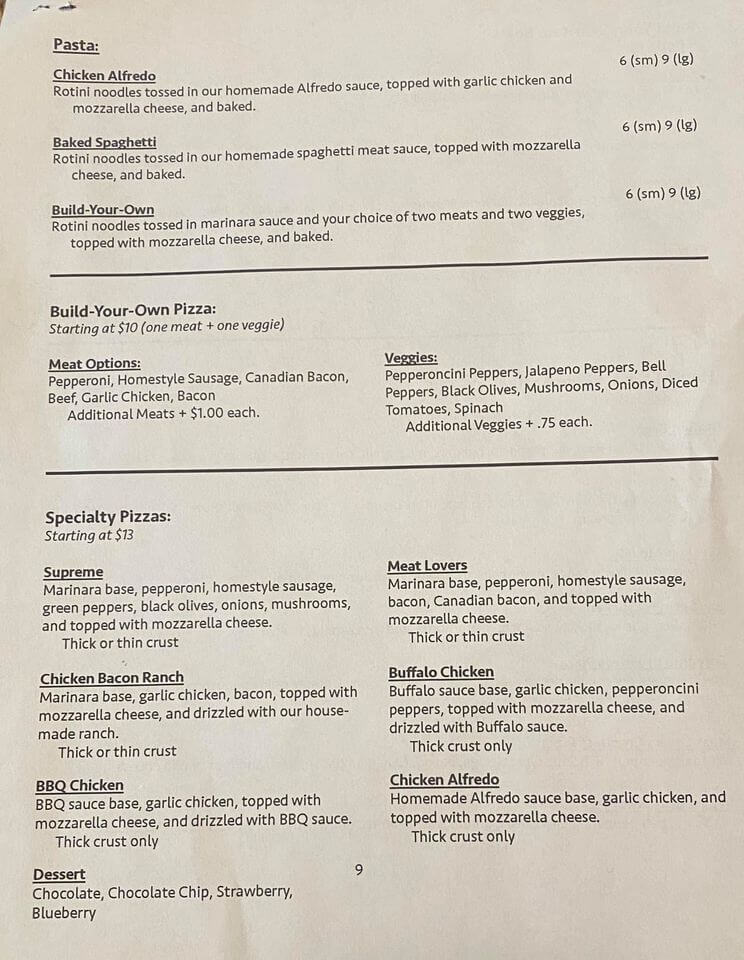

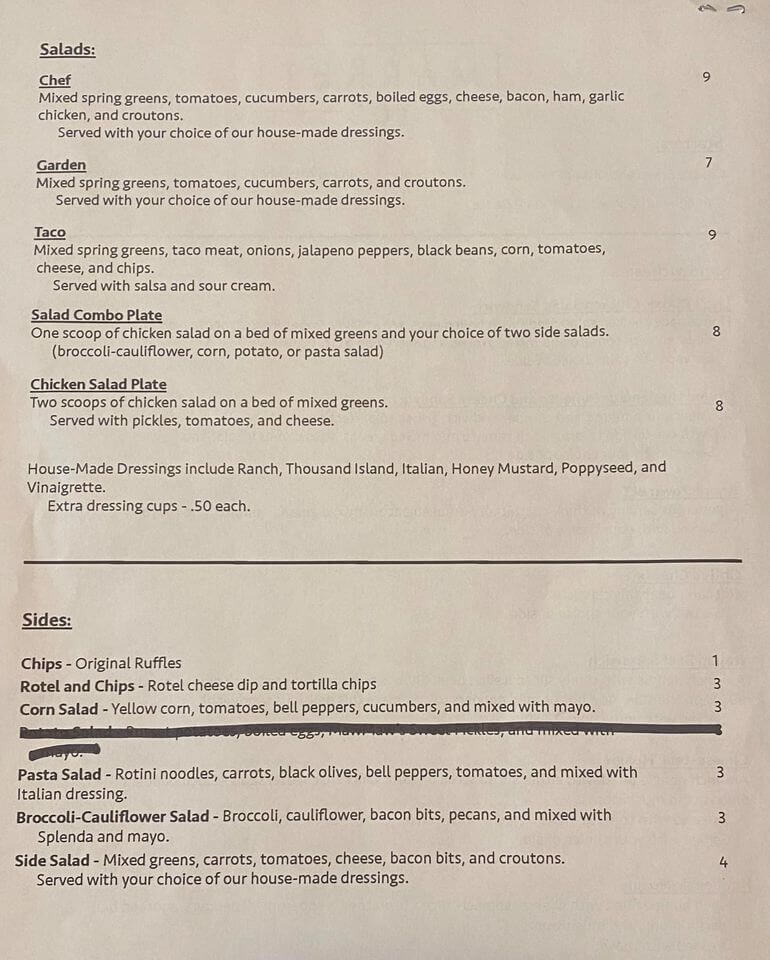

They provide blue plate lunch specials, starters, salads, specialty sandwiches, Keto boats, veggie plates, pizza, pasta, deserts, and more.

When You first walked in, the warm atmosphere is abundantly evident. From the plush sitting areas scattered about for friends to gather and discuss days events, artwork to admire, to the beautiful wood tables to enjoy your meal.

After being seated, I began soaking it all in. There was soft music floating through the space and a floral design area where the owners were creating beautiful arrangements for a wedding event they were catering.

While mulling around, you can also shop for some local goodies to take home and enjoy. Like their famous homemade chicken salad, pickled items, and much more.

The menu is packed with local favorites. I recently posed the question to loyal patrons of the eatery, “what’s your favorite menu item?” The response was not just one or two specials, but all over the menu! In fact, I was told that if you just closed your eyes and point, you can’t go wrong!

So, to get a good snapshot of what they have to offer we went with a menu showcase! A wide selection of local favorites from sandwiches, salads, lunch specials, and a large selection of veggies.

My selections included:

* Strawberry Salad

* Broccoli-Cauliflower Salad

* Corn Salad

* Tomato & Cucumber Salad

* Cheesesteak Hoagie

* Grilled Homemade Pimento & Cheese Sandwich

* Fried Chicken fillets

* Carrots

* Green beans

* Mac n’ Cheese

* Lima beans

* Fried okra

* Cream corn

* Mexican Cornbread & Traditional Cornbread

* A taste of Chow Chow

We’ve got a LOT to review, so let me start by saying that the Mmmm factor was strong in this selection. Meaning, I found myself repeatedly murmuring Mmmm with each first bite of the spread before me!

If your a veggie lover, then I highly recommend ordering a veggie plate. Each vegetable from the lowly string bean to the fried okra was seasoned perfectly. I could tell that each item was carefully tested and perfected before ever making it to the menu.

The salad selections were off the chain!!! From the corn salad to the tomato & Cumber salads. The vegetables popped with flavor, from each kernel of corn to the sliced cherry tomatoes.

The side salad that I was really excited about was the Broccoli and cauliflower salad. It is finely shredded and packed with subtle flavors. I could about make a meal of just this!

Now, for the best salad I’ve had made for me in, well… forever, the Strawberry Salad!!! It starts with a bead of fresh mixed greens and topped with strawberries, feta cheese, pecans, apple, and the best poppyseed dressing. You can order it with grilled chicken, but it’s purrr-fection as is! Y’all, I LOVE my protein, but this salad really made me happy.

The fried chicken looked really good, but I wasn’t expecting the wow factor from it. I stood corrected after my first bite! The crust was crunchy and flaky, with tender, juicy meat. Not greasy at all. I was told that they didn’t deep fry. Everything that required frying was sent through the pizza oven. From chicken to the fried okra.

For the sandwiches, the Grilled Homemade Pimento cheese is a local legend of sorts. Almost every other recommendation I received from patrons was for the grilled goodness! It can be a totally meat free meal, or have them add bacon to put it over the top!

Ok, for a sandwich totally over the top, the Cheesesteak hoagie is what you want! It’s filled with your choice of sliced steak or garlic chicken, cheese, sautéed bell peppers, onions, and mushrooms. Dressed with tomato mixed greens and mayo, served with your choice of side. I went with the traditional sliced steak to start, but I’ll definitely try the chicken on another trip. My hoagie was huge, tender, a little messy, and totally mouth watering! I’m writing about this several hours later and I’m getting hungry for it all over again!

Market 105 is not only a refreshing stop along a fun journey, but also a great destination for anyone looking for the hidden gem where all the locals go to eat, shop and gather!

P.S. What are your favorite menu items? We want to know! Leave your answer in the comments below.

Message me If you would like to have your restaurant, menu, and favorite foods featured in my blog. Over 17,000 local Foodies would love to see what you have to offer!

Facebook @ Eating Out With Jeff Jones https://m.facebook.com/eatingoutwithjeffjones

Instagram @ Eating Out With Jeff Jones

https://www.instagram.com/eating_out_with_jeff_jones/

Twitter @ Eating Out With Jeff Jones https://mobile.twitter.com/jeffjones4u

Support LocaL – LIKE • COMMENT • SHARE

http://www.eatingoutwithjeffjones.com