On a Sunday afternoon in 2017, a masked assailant came from around a building, shooting and killing Teresa Hughes’ son, Kendrick, as he stood talking to two friends at Pine Ridge Gardens Apartments in southeast Jackson.

A few months later, four John Does riding through the parking lot shot at Christine Christon, almost striking her minor son who was sitting in a car seat.

Christon dove from the spray of bullets, but the shooters hit Arsentell Burton 13 times, permanently incapacitating him. Burton’s pastor had dropped him off at the complex so he could help his uncle move.

After the shootings, Hughes, Christon and Burton did as dozens of Jacksonians before them: They hired a lawyer and filed suit, alleging out-of-state landlords failed to provide adequate security, fostering an “atmosphere of violence” at the federally funded complex commonly known as Rebelwood.

For years, these legal battles routinely led to monetary settlements, providing a modicum of justice for some of Rebelwood’s more than 400 tenants living in deadly and dire conditions, according to 15 lawsuits filed since 2010 that Mississippi Today reviewed.

But in 2019, lawmakers passed a bill known as the Mississippi Landowners Protection Act that has all but shielded landlords from liability for violent crimes committed on their properties. It has done so by limiting what constitutes an “atmosphere of violence” – a legal term describing conditions in which the property owner should have known injuries were likely and taken steps to prevent them.

Since then, local attorneys say liability has been harder to prove — and accountability less achievable — even if the landlord has neglected to take reasonable steps to secure the complex, such as hiring security, fixing broken lights, maintaining cameras or removing trespassers from the property.

Nicole Gibson launched such a battle. The Jackson native filed her lawsuit in 2022 after her son, Quindarius, was killed in the Rebelwood parking lot while the two were running an errand for family staying there. The incident occurred just one year after the Landowners Protection Act passed.

She went up against the companies responsible for the property at the time of her son’s death: The Texas-based owner, Rebelwood Apartments, and a New Jersey-based behemoth management company, Michaels Management Affordable. Last month, a Hinds County Circuit Court judge granted a motion to dismiss the case from a lawyer representing the companies – a hurdle Gibson’s attorney, Phillip Hearn, fears they won’t overcome if he appeals.

In an email, an attorney for Michaels Management Affordable said the company’s policy is not to comment on pending litigation. The Texas company that previously owned Rebelwood has shuttered.

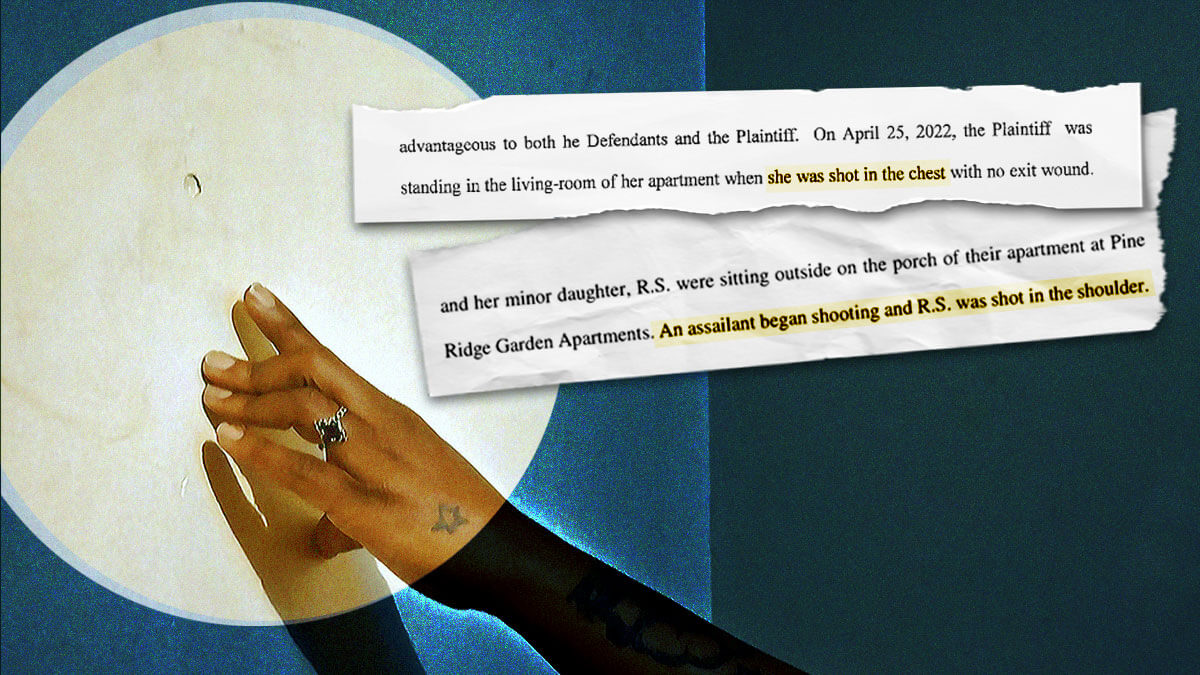

Gibson, 43, struggles with the notion of attaining justice for her son, nicknamed “Bubba,” whom she said had never been in trouble with the law – but for one time she took him to the county youth detention center for disrespecting her. He had graduated high school, worked at McDonald’s for years and played football for a local amateur team called the Magnolia State Knights.

“They just knew from the life that he lived that he was not supposed to die,” she said. “I tell everybody, ‘It’s a hard pill to swallow.’”

This is not to say plaintiffs lawsuits have done much to address the chronically poor conditions facing tenants who live in areas of Jackson with higher crime rates. Rebelwood remains one of the most notorious places to live in the city. Residents there continue to experience problems on a daily basis, from criminal incidents to grim living conditions of the kind that led Mayor John Horhn to convene a housing task force earlier this year.

In a recent meeting, task force members lauded the Landowners Protection Act for helping landlords weather the fallout of the decision by insurance companies, which were losing money to settlements, to discontinue coverage of claims stemming from violent crimes at complexes in Jackson.

“Every claim I’ve ever had on my properties is cumulative, it’s passed on. It’s like a credit check or a credit report,” said Jennifer Welch, a Jackson-based property manager and vice chair of the city’s housing task force. “It’s very unfortunate.”

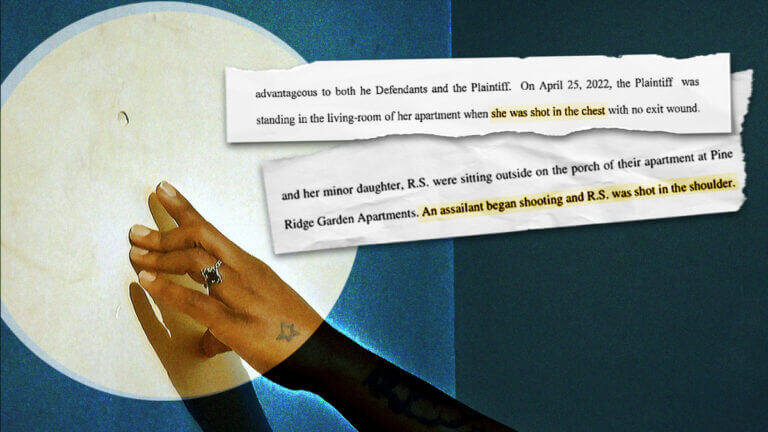

Meanwhile, Jacksonians who’ve been harmed at Rebelwood or lost their loved ones have little recourse but to file these lawsuits, known in the legal world as “premises liability” cases. Earlier this year, a woman filed suit after she was struck by a bullet that entered through her living room window, according to her complaint. Her case is pending.

“You can’t have all the laws be for the consumer, because then people can’t make money. I get it,” said Catouche Body, an attorney who represented Christon. “I just think the Landowners Protection Act goes a step too far.”

Former state Rep. Mark Baker, a Republican from Brandon who championed the bill, said he did not recall the Landowners Protection Act well enough to comment on its impact.

Before the 2019 act, lawyers frequently secured settlements in these cases. Hearn has several under his belt. When the parties couldn’t agree, the cases went to juries who were sympathetic to victims. In 2009, a jury awarded a $3 million judgment to the family of a woman whose body was found at Rebelwood (though the Mississippi Supreme Court later reversed that decision, ruling evidence she’d been killed elsewhere was withheld from trial).

But under the new law, Hearn and other attorneys must prove a landlord “impelled” the criminal conduct of the man who shot Gibson – a term plaintiffs lawyers told Mississippi Today they’re not sure how to interpret.

“What the hell does that mean?” Hearn said.

Attorneys must also show that violent conduct at the property in the three years leading up to an incident has resulted in three or more felony arraignments.

This might seem like an easy standard to meet at Rebelwood, where police have received calls of more than 100 shootings since the beginning of 2024, according to dispatch records obtained by Mississippi Today.

But when Hearn tried to gather the data, he said he hit a wall. Even though Rebelwood has been the site of numerous arrests for violent crimes in the three years leading up to Quindarius’s death, Hearn said he could not identify three felony indictments, the legal step proceeding an arraignment.

“I’ve subpoenaed the Hinds County District Attorney, the Hinds County attorney, the Jackson city attorney, the sheriff’s department, the Jackson Police Department, and every one of them says, ‘We do not maintain this information,’” Hearn said.

Where he might have once convinced a jury of pervasive violence using a 911 log – which shows roughly two calls a day from Rebelwood in recent years – or social media videos of fights at the complex that routinely go viral, Hearn said this kind of proof does not meet the redefined legal standard.

Hearn has already lost one case against the complex on behalf of another mother whose son was shot at Rebelwood while visiting his girlfriend. He can add Gibson’s case to the list. Hinds County Circuit Court Judge Eleanor Faye Peterson dismissed the case last month after Hearn could not find three arraignments.

“It’s a different age,” Hearn said. “And guess what, Rebelwood is more dangerous than ever.”

Government officials have taken far-reaching action in the past against Rebelwood, which opened in 1980. History lingers in the Civil War-themed street names still surrounding the troubled complex — Rebel Wood, Shiloh, Gray, Champion Hill.

In 1996, Brad Pigott, then the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of Mississippi, filed for forfeiture against the owners of the complex, alleging the number of drug complaints at Rebelwood showed they were not complying with federal standards.

Faced with the threat of losing the property, the owners pledged to install fences and screen applicants, resulting in what Pigott at the time called a “remarkable” turnaround.

Desiree Hensley, the director of the University of Mississippi School of Law’s Low-Income Housing Clinic, said city leaders could take similar action today. The council could seek to condemn Rebelwood for violating nuisance ordinances and force the complex to close until the landlord has improved the property.

“The local government’s hands are definitely not tied,” she said.

Kevin Parkinson, the Ward 7 Jackson city council member who represents Rebelwood, said shutting down the complex could send vulnerable people into the street, even as the city needs to do more in addressing its “unacceptable” conditions.

“Do we have solutions for 450 people to go elsewhere in the city?” Parkinson said. “I’m not sure that we do.”

Gibson was familiar with Rebelwood long before Quindarius was killed that day in 2020. Her sister had moved there in the late 1990s, around the time Quindarius was born. Her mother moved there a few years later. Gibson remembers kids playing water balloons and basketball and the security guard, Mr. Jimmy, who she said kept the complex in order.

“Mr. Jimmy had developed a relationship with the community out there,” she said. “He did not play.”

Hiawatha Northington II, a local attorney for Michaels Management Affordable who worked on Gibson’s case, remembers Rebelwood, too, as a place he used to visit friends during undergrad at Jackson State University in the 1990s.

Amenities like the Kroger on Terry Road – now an empty storefront – were close by.

“Whether you represent plaintiffs, defendants or neither, there are facts about the city of Jackson that are not in dispute and one of them is that areas like Terry Road have been systemically disinvested in for whatever reasons you want to attribute it to,” Northington said.

Improving conditions at Rebelwood would require a systemic solution, Northington said, which he feels individual lawsuits cannot achieve.

“Interpersonal conflicts can happen at the Country Club of Jackson just like they can happen at North Hills Apartments,” he said. “Some of those things are beyond what the civil justice system can address.”

Gibson was heading to Rebelwood on the afternoon of Saturday, April 25, 2020 to drop off some clothes to her brother, who was staying there, when Quindarius asked if he could ride with.

She didn’t think it was a good idea. Gibson knew Quindarius was at odds with a group of men at Rebelwood over the outcome of a dice game earlier that week. Quindarius had won $5, but when he tried to collect, the player threatened him. Gibson said she wanted to talk to that player’s parents, but Quindarius begged her not to, claiming the situation had been resolved.

“Me personally, I’m going to diffuse the situation,” she said. “I will never indulge in a kid’s beef.”

But when they arrived at Rebelwood, the 21-year-old son spotted a friend and told Gibson he was going to stay at the complex.

The mother recounted what happened next – a chaotic series of events that culminated in Quindarius’s killing – in a court filing in her lawsuit against Rebelwood. As she was speaking to her brother’s friend, she said she saw a group heading in Quindarius’s direction. Suddenly, he came storming toward her car, asking if he could borrow his uncle’s gun, telling Gibson he was “tired of them threatening him.”

She said no. Then she called the police. But instead of aiding Quindarius, Gibson said the officers escorted her off the property. Driving down the highway, she was on the phone with her twin sister, who was at the complex when gunshots rang out.

Gibson said she “snapped.” She characterizes the perpetrators as a “family which plotted his death” and ruminates on how things could have gone differently.

“I could’ve put a gun in my baby’s hand and let him do whatever he wanted to do, and I guarantee he would be home with me today,” she told Mississippi Today.

Without a weapon of his own, Gibson argues no one was there to protect him.

“You’ve got management just sitting out there,” she said. “They’ve got protection for them, but when it comes to the kids and the people living there, a lot of time they get in their car and leave the property because they be scared for themselves.”

Quindarius’ alleged shooter, 38-year-old Joe Willis, is out on bond, and Gibson is not optimistic that he will be convicted. She said it took years to forgive herself for bringing Quindarius with her to Rebelwood, only doing so after taking a job that sent her across the country, giving her space and time to think.

She concluded that she was not the only one responsible for her son’s safety that day. But now she feels alone in her pursuit of accountability.

“It’s just me and my attorney,” Gibson said before receiving notification the case had been dismissed.

- People in 15 counties can receive replacement SNAP benefits without application - February 6, 2026

- Retired Pittsburgh police commander is nominated as Jackson’s new police chief - February 6, 2026

- Local, state officials vet plans to secure Greenwood Leflore Hospital’s financial future - February 6, 2026