Editor’s note: A program on music icon Bob Dylan’s connection to Mississippi and the Civil Rights Movement will be held at 5:30 p.m. Wednesday at the Overby Center for Southern Journalism and Politics in Oxford. The panelists will be University of Mississippi professor R.J. Morgan, Mississippi Today’s Jerry Mitchell and Reena Evers-Everette, Medgar Evers’ daughter. The event will not be streamed live, but can be viewed in the coming days at https://youtube.com/@overbycenterforsouthernjou1739?si=zKUdKg3AIv4L_nzs.

Friends, let me just tell you, becoming a Bob Dylan scholar is not how I planned to spend my life.

In my previous careers, I was a sports journalist and a high school history teacher. I went to school to become an academic administrator. I teach media classes at the University of Mississippi, run two very successful scholastic press associations and serve nationally in a number of other capacities. I am deeply proud of this work. But unless you’re really into high school yearbooks and helping young adults find their voice (quick plug — you should be!), the story I’m about to tell is probably more interesting.

I was a casual Dylan fan in college. Like many folks, I knew he was important, and mysterious, and his lyrics definitely helped me make sense of many social injustices and get over many lost loves. As a young history teacher, I assigned some of his protest songs to my students for projects, but personally I was more into Johnny Cash and what the Drive-By Truckers’ Patterson Hood calls, “the Southern Thing.” Dylan was too New York City, too distant. I was fascinated by New York, too, but I lived in Mississippi. The South was my home.

By 2015, I was teaching at the University of Mississippi. Sensing time might be running out to see a legend live, I bought tickets for a series of Dylan shows, mostly just to pay my respects and visit a few friends spread out across the South.

I had low expectations. It was an excuse to travel.

What I discovered instead was an artist who was still very much alive and vibrant. Most of the songs he performed were from recent albums, so I understood very little of what was being mumbled into the microphone, but when I dug into the songs later, many struck me as even more stunning, and scholarly in their depth, than his well-known masterpieces from the 1960s and ’70s. When he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016, I realized this wasn’t just a popular American artist. This was a cultural icon who would one day be studied alongside Faulkner, Whitman and Hemingway.

I know that sounds a bit hokey.

But I work on a college campus, and when I hear visiting Shakespeare scholars talk about the importance of preserving the Bard’s “First Folios” (the 235 surviving copies of the first collection of Shakespeare’s plays, published in 1623), it sounds a lot like the reverent whispers I hear “Dylanologists” use to discuss bootlegs of a pre-New York recording at a friend’s Minneapolis apartment or the marked-up pocketsize notebooks he used to sketch out lyrics for “Blood on the Tracks.”

Both camps analyze these artifacts as if they’re the Dead Sea Scrolls. That’s what scholars do. Every scrap of information preserved can offer new ways of seeing and understanding a historical figure, even one who does not want to be seen or understood, like Dylan.

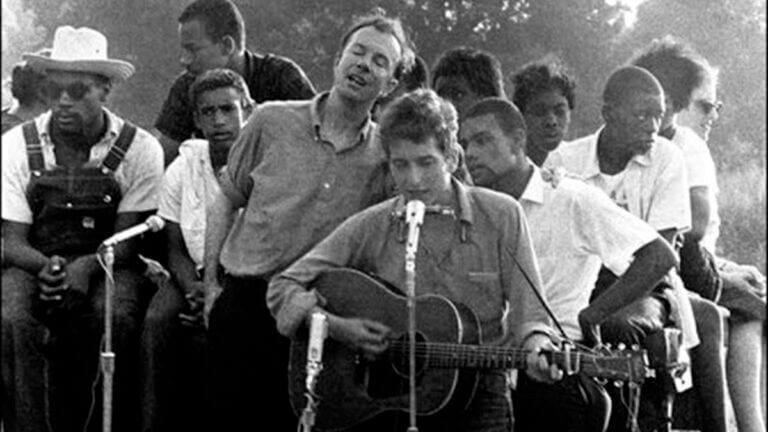

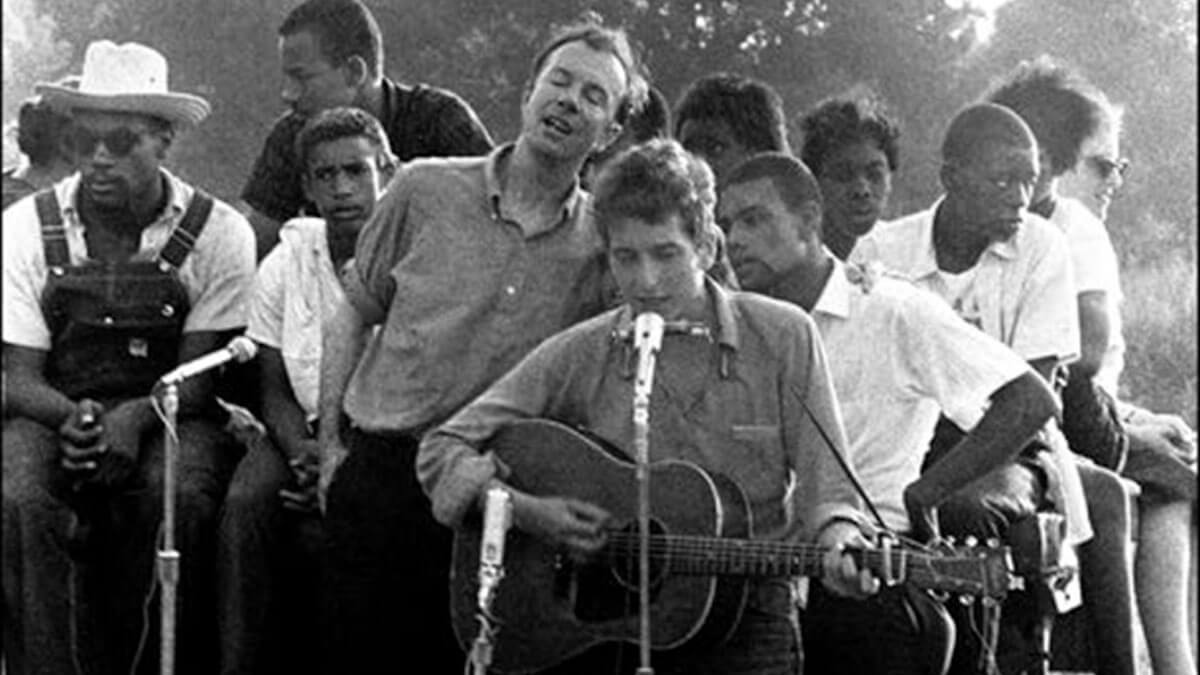

Around this time I also ran across the short, famous video clip of Dylan performing in a cotton field outside of Greenwood “Only a Pawn in Their Game,” his song about the assassination of Medgar Evers.

The novelty of it caught my attention first. I was well acquainted with Evers and his heroism. I’d taught Mississippi studies. Now here was this song, and this poignant performance. I needed to know more.

So I began casually accumulating any information I could find. The event turned out to be the Delta Folk Jubilee, a voter registration rally put on by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in July of 1963.

Folksingers Pete Seeger, Theo Bikel and Dylan — all white — came down and performed with the Freedom Singers as a way to show support for local Black people, who were fighting for the right to vote, and to help export their story back to the rest of America by generating news coverage.

SNCC’s press release claims it was the first integrated public gathering in the history of the Delta.

Future congressman John Lewis was there as SNCC’s newly-elected chairman. Local law enforcement put up “No Parking” signs along the road to deter attendance, then stood hovering across the street, armed, while sharecroppers traded stories of police brutality.

Dylan played just two songs. “Pawn” was one, and this was its debut. Evers’ body had been buried for less than three weeks. The other song was “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

The whole affair was bold, risky and dangerous. The more research I accumulated, the more my reporter’s brain activated. This was a major historical event, not just for Dylan but for Mississippi. So I set out to try to document my little sliver of “Dylanology” by tracking down those who were there and recording their stories.

Among others, I’ve interviewed Courtland Cox, the SNCC worker who picked up Dylan at the airport in Jackson; Bob Moses, leader of the Greenwood movement and architect of Freedom Summer; and Dorie Ladner, who dined with Evers the night he was murdered and later became friendly enough with Dylan that he spoke of her in song:

I got a woman in Jackson

I ain’t gonna say her name

She’s a brown-skin woman, but I

Love her just the same

Both Moses and Ladner have now passed on, but my interviews are ongoing. If you know anyone who attended this event or has any information that might be useful, please reach out.

Researching Dylan’s Greenwood trip led me to dig deeper into the rest of his career and catalog. He may be from Minnesota, but his roots run almost immediately to the South.

In addition to Lead Belly, Woody Guthrie and Hank Williams, Dylan cites Robert Johnson and other Delta Bluesmen as major early influences. According to my colleague Jason Cain, the radio waves carrying all that music up the Mississippi River to Dylan in Hibbing were the same ones falling on Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, and a young Levon Helm, Dylan’s future bandmate.

Beyond Evers, Dylan penned civil rights anthems about Emmett Till and James Meredith. He cut major, career-defining records in Nashville, Muscle Shoals and New Orleans. His latest studio album, “Rough and Rowdy Ways” (2020), is named after a song by Meridian’s Jimmie Rodgers.

He wrote a song called “Mississippi” in the late 1990s that was first cut by Sheryl Crow. The hook comes from a 1947 prison work song on Parchman Farm:

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

I grew up just outside of Jackson in the tight-knit, working-class community of Pearl. As a native, these legacies are very important to me. Mississippi is the birthplace of America’s music, and as such, I believe it should be a leader in the study of America’s most consequential musical artist, which is Bob Dylan.

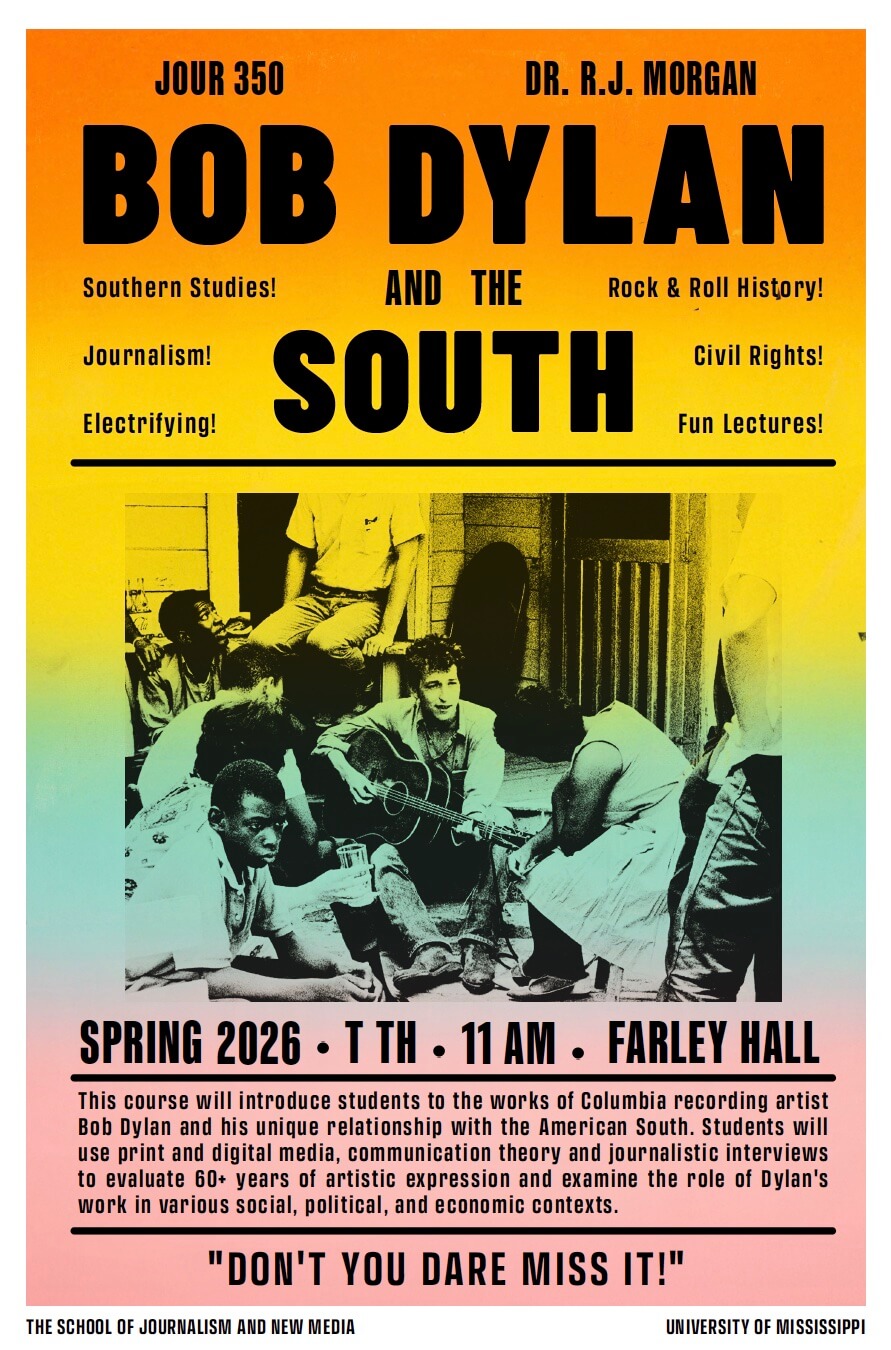

So, I developed a course called “Bob Dylan and the South” last year for the School of Journalism and the Center for the Study of Southern Culture. It was extremely well-received, and faculty voted earlier this fall to make it a permanent part of the catalog. Registration for next spring’s section begins later this month.

Dylan has been the topic of academic study for more than 40 years. Harvard, Penn, Texas, Berkeley and countless others offer courses on him. The University of Tulsa houses the Institute for Bob Dylan Studies. But no other college campus in America could give its students a better education on Dylan’s southern connections than the University of Mississippi.

We have Greg Johnson and the Mississippi Blues Archive, one of the largest collections of Blues holdings in the world. We have Scott Barretta, whose award-winning “Highway 61” Blues show airs every week on the Mississippi Public Broadcasting radio network. We have David Swider, the insanely knowledgeable musicologist who owns End of All Music record stores in Oxford and Jackson’s Fondren neighborhood.

We have professors Mark Dolan and Vanessa Charlot, who’ve researched Dylan’s lyrical and cultural connections to Florida and the Caribbean, respectively. Jacob Justice in the Department of Writing and Rhetoric presented his research on Dylan’s relationship with the Beatles at the World of Bob Dylan academic conference in Tulsa this summer, alongside myself and some 300 others.

Our very campus is tied to Dylan, who wrote “Oxford Town” about the riots resulting from Meredith’s enrollment as the first Black student in 1962. He sings:

Two men died ’neath a Mississippi moon

Somebody better investigate soon

One of the two men who died was Paul Guihard, a French journalist. He was the only journalist, in fact, to die covering the Civil Rights Movement. My retired colleague Kathleen Wickham spent the bulk of her career researching Guihard and the integration riots. In 2010, the Society of Professional Journalists declared the Ole Miss campus an historic site in journalism. The plaque stands outside my building.

Guihard’s murder has never been solved, but Wickham quite literally became the “somebody” Dylan called for in song back in 1962. When she shared her work with my students last spring, they could look down from our classroom windows at the riot site below.

Everyone else mentioned above spoke with my students, too. The course culminated with students having to produce their own podcasts, with original interviews and research, on a Dylan-related topic. We aired their work on campus radio over the summer. Collectively, we used Dylan as a throughline to explore a variety of topics, crisscrossing disciplines and lenses. The contours of Bob Dylan and the American South are those of America itself.

The music tells the story.

At a time when the public is openly questioning the value of higher education, courses like this speak to the relevance of scholarship in everyday life. Where else and when would students, especially out-of-state students, learn this cultural heritage?

And if they have fun along the way, so what? Universities shouldn’t only have fun on Saturdays.

College students are often painted as flighty and entitled (and some of them are). But those enrolled in my course last spring, hailing from more than a dozen majors across campus, were thoughtful and inspiring.

In her final reflection essay for the semester, one student wrote:

“I was born and raised in Hernando. I wasn’t always proud of that fact. … I never even knew the culture that surrounded me before I made it to college. Mississippi is one of the most historically rich places in the entire country, and nobody talks about it. So much music originated here. It is the state of American Music. Where would we be without Mississippi musicians? There is so much new gained respect I have for this place, and I am lucky to have been born here.”

Mission accomplished.

Bio: R.J. Morgan is an instructional associate professor in the School of Journalism and New Media at the University of Mississippi and executive director of both the Mississippi Scholastic Press Association and Integrated Marketing Communication Association. He was managing fellow of the Overby Center for Southern Journalism and Politics from 2022-2024. He is a former high school educator and a finalist for Mississippi Teacher of the Year in 2011. He is working on a book project about the Delta Folk Jubilee of 1963. Morgan has a Ph.D. in education leadership from the University of Mississippi and earned undergraduate and master’s degrees at Mississippi State University. He lives in Oxford.

- State fire marshal is investigating troubled Unit 29 at Parchman prison - February 26, 2026

- Mississippi’s Winter Storm Fern losses exceed $107 million, state insurance department says - February 26, 2026

- DNA evidence linked to a Greenville homicide is missing. Now the finger-pointing begins - February 26, 2026