Lucinda Wade-Robinson watched her 22-year-old son, Zachary, hit the pavement feet from her front door on April 29, 2014. She saw the shooter and his friends hightail it to the highway. Her neighbor helped her son into a her car as he bled out. After he was pronounced dead at a hospital and investigators processed the crime scene in her front yard, she says she waited days for the fire department to spray his blood from her bullet-strewn driveway with a fire hose.

Wade-Robinson, worried she wouldn’t be able to cover the $8,000 funeral bill, applied in Hinds County for help from Mississippi’s victim compensation program, a fund that each state has to reimburse victims of crime and their families for funeral expenses, medical costs, crime scene clean-up, execution travel and counseling, among other disbursements.

A funeral home director told Wade-Robinson about it and suggested she apply. But the state attorney general’s office, which administers the program, denied her claim, alleging her son was responsible for his death, a type of denial known as contributory misconduct.

“It was a nightmare,” said Wade-Robinson.

Mississippi’s definition of what kind of conduct contributes to one’s death is broader than most states, and a Mississippi Today investigation found that Wade-Robinson’s denial is not unusual. Mississippi has one of the highest rates of denials attributed to “contributory misconduct” when compared to other states, with about 6% of all applicants getting denied for this reason.

Mississippi’s overall denial rate is 42%, for years 2021 to 2024. From 2021 to 2023, roughly 2% of claims were reduced.

Arkansas, West Virginia and South Dakota have similar outcomes, with all four states rejecting for contributory misconduct at roughly three times the national average, according to federal data collected between 2017 and 2023.

It’s the language of the law that makes Mississippi unique, according to Jeremy Levine, a professor of sociology at the University of Michigan who’s published research on victim compensation. If the victim makes “threatening and obscene gestures,” uses “fighting words,” even if the behavior was not directly connected to the circumstances of the person’s death, they would be ruled ineligible for compensation. The law also asks administrators of the fund to consider the victim’s behavior in the weeks leading up to their death.

The law is broad and open to interpretation, particularly when it comes to blaming victims for inciting their own killing.

“The provocation point is really fuzzy,” said Levine, and Mississippi “is on the top end of vagueness and discretionary openness.”

More than a third of compensation applicants in Hinds County were denied reimbursement from 2021 through 2024, according to records obtained by Mississippi Today. The attorney general’s office rejected 169 claims because of administrative rules like contributory misconduct. It approved 291 claims with a payment.

Mississippi’s victim compensation records are secret, according to a law enacted in 2000, meaning there is no way to assess racial and geographic bias in verdicts. And while these types of denials are falling nationwide, according to federal records, they are increasing in Mississippi, the poorest state with the highest homicide rate per capita.

“A lot of these exceptions make assumptions about communities and blame victims for their own deaths,” said Rep. John Hines, a Democrat from Greenville, a city with one of the highest gun homicide rates in the state.

The attorney general’s office chose not to provide comment. A spokesperson from the Office of Justice Programs in the U.S. Department of Justice wrote that eligibility requirements are at the discretion of states.

The attorney general paid victims an average of $1,877 less in 2024 than it did the previous one. The average claim was $2,459 in 2024.

Contributory misconduct rejections can present an arbitrary barrier to financial help for victims of crime, said Tina Rogers, a victim assistance coordinator in Columbus, Mississippi.

“It is subjective and can be skewed depending on the type of crime,” wrote Rogers.

Not innocent enough

Wade-Robinson didn’t leave her house after her son’s death. Zachary Robinson had still been living in the family home; his sudden absence was painful. She was spending more quiet afternoons replaying the killing she watched take place from behind her front door.

Wade-Robinson’s attorney appealed the contributory misconduct denial. As she waited for an answer, the prosecutor informed her that charges would not be pursued against her son’s alleged shooter and the six men who accompanied him. The Jackson Police Department determined Robinson’s murder was a self-defense killing. The victim compensation director swiftly issued a second denial letter, citing the department’s finding.

“It was like being victimized again,” Wade-Robinson said.

Wade-Robinson was hurt. Seven men had come to their house with weapons, she said. After one man came to their door to threaten his mother, Robinson drove home with a concealed weapon and yelled at the men to leave their house, Wade-Robinson remembers. In return, they shot him. And as the seven men sped off, her son’s friend, Lamont Ford, returned fire.

Mississippi has a castle doctrine or “stand your ground” law. But the attorney general’s hearing officer felt it didn’t apply.

“Although the Hearing Officer certainly recognizes Victim’s Second Amendment right to bear arms, Victim was clearly the initial aggressor and his display of a firearm in this circumstance caused another individual to fear imminent death,” the hearing officer said.

Local law enforcement must typically summarize the victim’s involvement in the crime and fill out a document that asks if the victim’s behavior in any way contributed to the person’s death because of drugs and alcohol or fighting words. When it comes to how law enforcement officers interpret how and if a victim’s conduct led to the individual’s death, rationale varies by department and agency.

Law enforcement initially charged Ford, Robinson’s friend, with murder in Robinson’s death, but an assistant district attorney in that office couldn’t explain why. The murder charge was dropped but a shooting into a dwelling charge remained. Ford’s shots missed, entering a nearby home and a delivery driver’s car.

Wade-Robinson didn’t miss a day of the trial. And when the jury found Ford not guilty, Wade-Robinson’s attorney requested that the victim compensation division reconsider its denial of her claim.

On March 31, 2016, at a private hearing held at the attorney general’s office in Jackson, Wade-Robinson’s claim was denied for the second and final time. The hearing officer cited her son’s “displaying of his weapon” and his refusal to call the police. They also cited his decision to drive to his home where two cars of potential adversaries were parked.

“He was acting in a provoking manner that was greater than that of the offender,” testified Amy Walker, director of Crime Victim Compensation. “Robinson had used fighting words and obscene and threatening gestures based on the information that we received. And whether or not there was a causal relationship between his actions and the incident, I determined that there were.”

“So, I did find some level of responsibility on his part,” she added.

Being under the influence and taking risks isn’t behavior that would lead to outright denials by victim compensation programs in most other states.

The director also mentioned Robinson’s gun possession.

Mississippi has the most relaxed gun laws in the country. During the pandemic, then-Mayor Chokwe Antar Lumumba tried to temporarily ban open carry of firearms in the wake of increased violence only to have Attorney General Lynn Fitch ask him to rescind it because it was in violation of the state’s open carry law.

During the trial of Lamont Ford, witnesses were grilled about their gun possession too.

“I fear for my life when I come to Jackson,” said one of the witnesses. “I always keep a gun in my car.”

‘A national disgrace’

Some advocates, academics and victims argue Mississippi’s crime victim compensation division has failed to live up to the vision set forth by its chief architect, President Ronald Reagan.

In 1982, Reagan assembled a task force that looked into how national, local and state policies treat crime victims. The task force found treatment of crime victims to be a “national disgrace.”

Reagan signed the Victims of Crime Act into law two years later, which established a fund for each state to disperse to “innocent” victims of crime. In 1991, Mississippi established its division responsible for dispersing money.

Since establishment of the fund, many states have narrowed their definitions of “contributory misconduct” or removed it as a criterion for eligibility because of disproportionately high rejection rates for minorities and advocacy efforts from victim rights’ groups.

In a 2005 Kansas Supreme Court ruling, judges found that “contributory misconduct” must be directly contributory, ruling against the state’s Crime Victim Compensation Board. A couple had victim compensation diminished for their son who had died in a car wreck that was no fault of his own. The board had found that their underage son had drunk alcohol the night before and therefore had a blood alcohol content level that was illegal for someone his age at the time of his death. The board wrongfully reasoned, the court found, that this crime had contributed to his death.

Ohio in 2021 put a stop to rejections due to mere drug possession and allegations made about victims’ behavior leading up to their death. Pennsylvania prohibited the denial of claims for funeral reimbursements based on “contributory misconduct” in 2022. New Jersey, Delaware, and New Hampshire have made similar changes.

The Justice Department announced it would look into how subjective metrics like “contributory misconduct” can disproportionately discriminate against Black applicants. The DOJ’s announcement came on the heels of a 2024 Associated Press investigation, analyzing data in 23 states, which found that Black applicants for victim compensation were disproportionately denied at a higher rate for subjective reasons “rooted in implicit bias” like contributory misconduct.

On April 5, a group of 18 attorneys general, including Mississippi’s, joined Alabama’s attorney general and objected to what they perceived as the DOJ’s overreach. They found the updated guidelines “exceeded the agency’s authority” and “could result in the States losing vital funding for their victim compensation programs.”

“State resources available to compensate crime victims are not limitless,” argued Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall. “States thus have always had to make choices about how to justly allocate these funds,” he wrote, and this includes considering “whether an applicant was partially responsible for the crime that harmed him rather than being a purely innocent bystander.”

Scant resources for innocent crime victims is a common argument made by proponents of using the “contributory misconduct” stipulation to assess victim compensation claims. Applicants in Mississippi can also be denied if the victim or applicant has a prior felony conviction, didn’t cooperate with law enforcement or prosecutors and applied for ineligible reimbursement categories like property damage, to name a few.

At the end of Financial Year 2024 after all the reimbursements were paid, Mississippi’s crime victim compensation fund had at least $2 million unspent.

By the end of 2021’s reporting period, with 81 more homicides reported in Mississippi, rejections on the basis of contributory misconduct nearly doubled despite a slight increase in applications.

Crime victim compensation programs are mostly funded by court fines and fees, not taxpayer money. Traffic tickets, felony murder convictions and federal judgments all generate money for the fund. State legislatures and the federal government appropriate money, too.

Even Mississippi crime victims who are approved for victim compensation can wait months to over a year for reimbursement. Neighboring Louisiana offers $500 in emergency funds to victims to help cover immediate costs like medical expenses, crime scene clean-up and lost wages.

In 2023, reimbursements for funerals accounted for more than half of funds paid out. Funeral home directors can fill out forms for crime victim compensation, too, applying on behalf of the victim.

Scotty Meredith runs Meredith-Nowell Funeral Home in Clarksdale on top of serving as coroner for Coahoma County. The small Mississippi Delta city experienced a 250% increase in homicides from 2023 to 2024, with four in 2023 and 14 in 2024. Meredith’s funeral home has gained a reputation in the county as a place to seek help filling out applications for crime victim compensation. But when it comes to the contributory aspect, he finds it hard to anticipate who the division will reject.

“It helps the family at a tough time,” he said, sitting in a room dedicated to grief counseling and funeral planning. The Delta is the state’s poorest region and has the highest number of gun homicides per capita. “It takes a big burden off a family that is already grieving.”

In Mississippi Today’s discussions with 17 funeral homes across the state, 10 confirmed they no longer handle services for families who depend on victim compensation funds to pay for the funeral. It’s too much of a gamble for some, given how subjective the criteria can be.

Funeral home director William Jefferson Jr. of W.H. Jefferson Funeral Home in Vicksburg helped out a young apprentice’s family with a discounted rate after their claim for their son’s funeral was rejected.

The director had cited marijuana found in his toxicology report, Jefferson said.

Her own detective

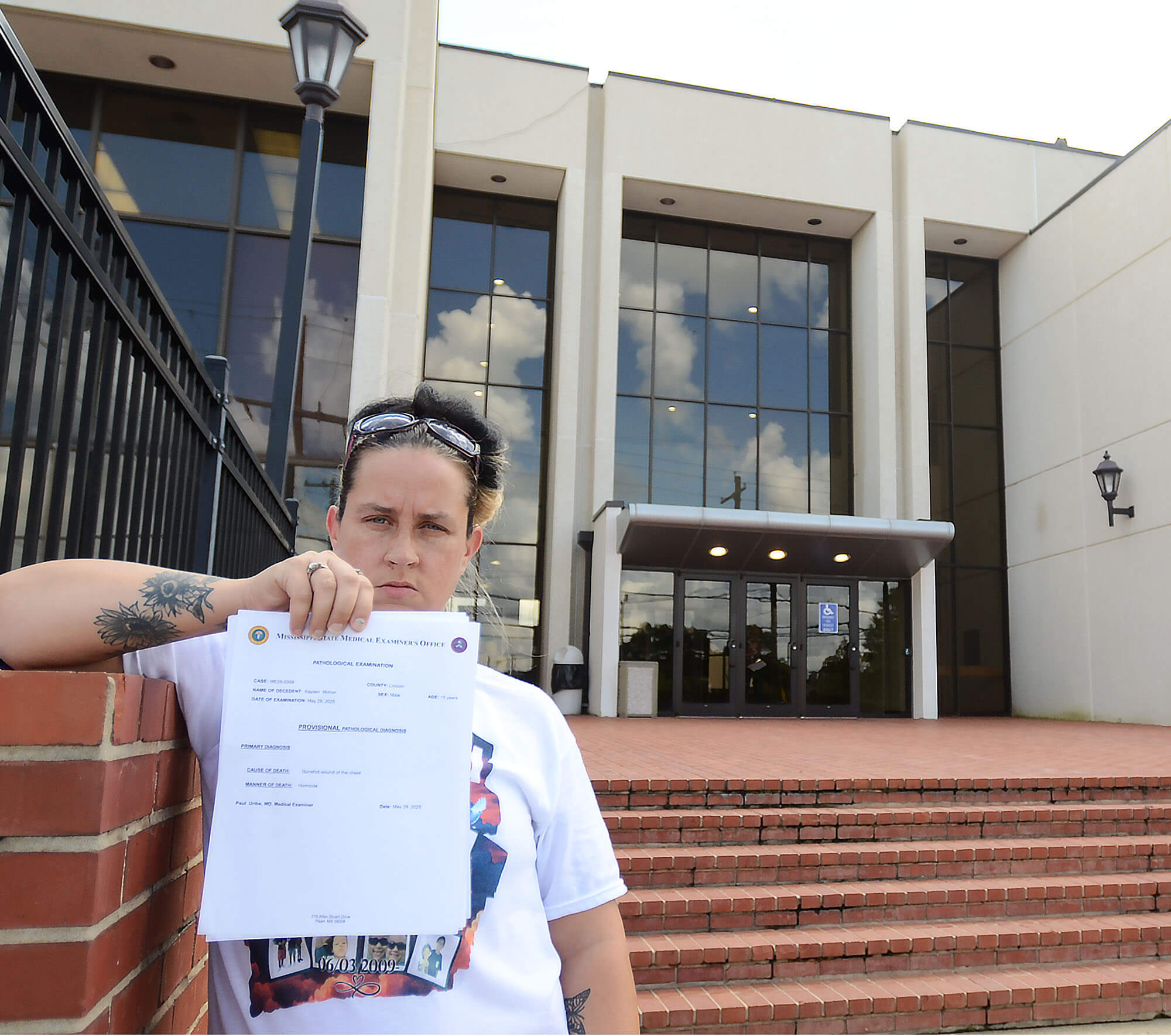

Marijuana was cited in 15-year-old Kayden Mohon’s toxicology report – and in the denial letter sent to his mother Angel Mohon.

Angel Mohon found out about the killing through a social media post circulated by the teenagers she believes responsible for his death. For her, it was a nightmare come true. On a day when she should’ve been celebrating his 16th birthday, Mohon was burying her son.

During Memorial Day Weekend, he was driving his friend home after a pool party in Brookhaven. As he braked near the stop sign on Ozark Lane, shots rang out from the field beside him. His car was riddled with bullets in seconds.

A home security camera captured the shooting: Kayden Mohon opened the driver’s side door as bullets continued to hit the car and the gravel road in front of him. He was driven home to the friend’s house down the street where he succumbed to his injuries and police were called.

Brookhaven Police Department communicated to the attorney general’s office that his death was the result of his own negligence. They labeled it a shootout – and made no arrests. Allegations made in the crime victim letter of Mohon’s firearm usage are not supported by the incident report, which doesn’t identify him with a gun.

Angel Mohon reached out to Brookhaven PD to share the home security camera footage that might exonerate her dead son. But they wouldn’t watch.

So, she took off work as a home health care aide and decided to investigate.

She first tracked down the Toyota Corolla in which her son was killed. She traveled to an Enterprise Rent-A-Car lot in Natchez where the vehicle was towed. She interviewed neighbors who lived on the street where the shooting took place, one shared home security camera footage that cast the incident in a new light. She interviewed a witness to the killing, her son’s friends and knocked on the doors of local parents.

In the weeks after Kayden’s death, Kenny Collins, Brookhaven’s longtime police chief, stepped down. Under his leadership, the department was criticized for incompetence and shoddy police work. The county’s grand jury that considered more than 60 criminal cases found that the “complacent” Brookhaven Police Department “shows a lack of professionalism,” “has a habit of witness blaming” and is prone to “poorly investigating their cases.”

Under new leadership, the police department is reinvestigating several cases and is hiring a new investigator. When Mississippi Today brought Mohon’s case to the new chief’s attention, he confirmed that the case will undergo new scrutiny.

Mohon is still afraid to leave her home. The boys responsible for her son’s murder have threatened to target her next. They have driven by her home and harassed the family from their vehicles, she says. One wears a sweatshirt bearing an image of her son’s dead body.

“It hurts,” she said. “Every time I sit still for too long or I close my eyes, all I see is my baby’s body lying on the ground.”

Kayden was taking classes in welding at the time of his death. His mom was picking up extra shifts as a home health care aide to help pay for the costs of his training. Angel Mohon had also recently taught him to drive.

“Why kill my child? Because he had a life, he had a future. He had hopes and dreams that he was fulfilling.”

Mohon doesn’t know how she will come up with the $7,000 to pay for the funeral. She is three months behind on her car payments and was told she would lose her only source of transportation next month if she couldn’t come up with $500.

The victim’s voice

When it comes to assessing a victim’s hand in their death, law enforcement officers are the first arbiters. In Mississippi, officers must file their assessment of victim involvement in a crime within 30 days of the victim’s survivors applying.

A law enforcement officer in Sunflower County, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of losing his job, said he checks the contributory box only if the victim “brought the fight to somebody else.”

Funding for local law enforcement agencies prevented officer salaries from keeping pace with inflation – and many Mississippi departments operate on small budgets with less staff than they require. Three police chiefs interviewed complain that witnesses are often reluctant to share information, and the department lacks the budget to retain talent.

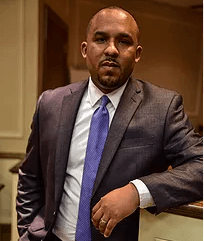

Greenville Police Chief Marcus Turner recently mandated that all officers provide crime victim compensation applications to families regardless of what responding officers make of the crime scene at first. Even the family of victims responsible for their deaths need our support, Turner said. He also brings sympathy cards to the victim’s home before any interviews take place.

“It’s our responsibility to speak for the victim,” Turner said. “When there’s a murder, you have a suspect and a victim. The victim can’t say anything.”

Mississippi has few nonprofits or charities dedicated to helping crime victims cover even basic burial costs and that provide counseling to immediate relatives of homicide victims. Churches occasionally step in to cover burial costs for longtime parishioners who were the victims of crime. Stewpot, a homeless shelter in Jackson, will occasionally help pay for burial costs of low-income crime victims.

“The survivors of homicide are forgotten on every level,” said Felecia Marshall, founder and CEO of Grant Me Justice, a nonprofit that helps crime victim families navigate the criminal justice system, cover the costs of counseling and pay for burials. “Many parents are not prepared. There are so many layers that the family has to deal with while they are grieving.”

Legally, counties must have a plan in place for burial of paupers, or those who die without a place for their body. State law does not mandate that a pauper burial be marked, though many counties do.

Unmarked

No tombstone marks Chris Magsby’s grave. Jean Tenner, Magsby’s mother and a longtime employee at the Horseshoe Casino in Tunica, had a hard enough time covering the costs of his funeral before her claim was denied.

“I shouldn’t have to do this all by myself,” said Tenner, a single mother with another son in the armed services.

In 2023, Magsby was driving his youngest son when his cousin Decedron Johnson began to threaten him over the phone, trailing him in his car. The two pulled their cars off the road and when Magsby stepped out of his, Johnson started shooting. Johnson was later arrested in Clarksdale, and Magsby was pronounced dead at a hospital.

At the funeral, Magsby was laid to rest in a scarlet casket. Tenner still didn’t know how she’d pay for it. She neglected to make her car payments so she could save to give her son a proper sendoff. But she never saved enough.

While Johnson was out on bail pending a trial, the victim compensation division was still investigating Tenner’s claim for victim compensation.

On July 22, 2023, over a month after the funeral, Tenner got her response: The Mississippi Attorney General’s Office had rejected her claim on the grounds her son had been on probation for a felony conviction. Magsby was never convicted of a felony.

On Aug. 18, 2023, her claim was rejected for a second time, this time on a posthumous accusation that he committed a felony at the time of his death. Police allegedly found a bag of cocaine in his car, which indicated to the attorney general’s office that he was not an innocent victim at the time of his death, and therefore, his mother would be ineligible for compensation.

Also, his posthumous commission of a felony broke his non-adjudication agreement, meaning he was back under the supervision of the Mississippi Department of Corrections – another disqualifier. The initial charge was for “trespassing” into a local business when he was a teenager.

Tenner’s denial is hardly unique in the Mississippi suburbs of Memphis, Tennessee, where a tough-on-crime approach by law enforcement often puts victims under suspicion. The AG’s office denied over half of DeSoto County victims’ compensation claims from 2021 through 2023, records show.

Tenner struggled to make sense of the division’s decision in light of what she knew about her son. In the years before his death, Magsby had received his high school equivalency diploma, moved from the Delta to Horn Lake with his burgeoning family and secured a job at a nearby factory.

Tenner thinks of her son every day, especially how he used to love to take his kids on trips to Disney World and to water parks in nearby Arkansas. She hopes her grandkids will get to go on another trip soon – but they haven’t since Magsby’s passing. Her grandson, who witnessed his father’s death, needs therapy, said Tenner, but with her debts from her son’s death, she feels that counseling is a long way off for the toddler.

As crime increases, more parents are finding themselves struggling with the financial aftermath of their child’s murder, said Turner, Greenville’s police chief.

“Now, we’re living in a time where young people are losing their lives every day, and the parents are not in the position to have them covered under any type of burial or life insurance,” he said.

Every witness or person present when Robinson, Magbsby and Mohon were killed, including the victim, were younger than 30. Since 2013, the number of young crime victims has more than tripled; 338 Mississippians younger than 34 were gun homicide victims in 2023.

Acceptance

Every year, Wade-Robinson attends the Christmas tree decorating party for crime victims hosted by the attorney general’s office. The office usually hires musicians to sing hymns and holiday songs. The families of crime victims hang ornaments on branches while the staff greet grieving families. Last year, she cried, touched by a rendition of “How Great Thou Art.”

Scott Colom, a district attorney in Columbus, organizes a similar event for each family at the end of trials. He plants a tree with the victim’s family in an intimate ceremony outside the courthouse. Victim coordinator Tina Rogers sings hymns and popular music.

“Grief is going to be long, but this tree’s going to be here longer,” Colom said, explaining the ceremony. “The victim’s going to be here, too. They can survive it. They can withstand it. They’ve got a reason to live on.”

He has also appealed crime victim compensation denials, in one case because the applicant was a few days from meeting the five-year threshold from a felony conviction. His appeal was ignored. The division upheld all 54 denials that were appealed on paper or in a hearing in 2021, 2022 and 2023, according to records obtained.

“The only way we’re going to be able to successfully prosecute violent crime is cooperation from victims and survivors,” Colom said. “And if victims and survivors and witnesses have a negative impression of the criminal justice system, that decreases the chances that they’re going to cooperate, which decreases our chances of being able to prosecute crime.”

Restitution is the only other type of compensation available to crime victims. Their families can request that a judge order the offender to pay them for counseling and property damage, among other expenses. But restitution isn’t possible until a person has been successfully prosecuted – an obstacle for mothers of murdered sons in counties with low clearance rates.

Wade-Robinson keeps her son’s room close to how he left it 11 years ago. His car sketches are still taped behind a chest of drawers topped with model cars, trophies and certificates.

Robinson was involved in his community, Wade-Robinson remembers. He used to love to ride his grandfather’s horse at his farm in Terry and hunt deer. Robinson was recruited to play the tuba in high school. He won an academic honor in his senior year and graduated with honors from his automotive course.

“It’s hard to forget someone who gave you so much to remember,” began a resolution honoring Robinson, issued by his high school a week after his death. “We recognize that this temporary loss is Heaven’s ultimate gain.”

The city of Jackson did finally settle a wrongful death suit with Wade-Robinson’s family for an undisclosed sum on Dec. 13, 2017.

But grieving and seeking justice for her son still keeps her up at night.

“I just can’t understand how you treat victims like this,” she said.

Editor’s note: Mississippi’s Attorney General’s Office counts applications abandoned by claimants before they provide receipt of a service for compensation as “Approved With No Award.” From 2021 to 2024, 1,301 applications fit into this category. Mississippi Today chose to only tabulate applications where a receipt was provided by the applicant to substantiate their claim for financial relief. Here you will find a county breakdown with all categories included.

- State Supreme Court considers reviving former Gov. Phil Bryant’s lawsuit against Mississippi Today over welfare scandal coverage - February 18, 2026

- Winter storm update: Mississippi still waiting on fed declaration for individual assistance, lawmakers crafting plan to fund recovery - February 18, 2026

- Shy of special session, Mississippi school choice appears dead - February 18, 2026