The Front Row

An essay by Kiese Laymon | October 6, 2020

I hate italics.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

I’m writing a series of short essays for Mississippi Today. The series is focused on three deeply southern twentieth century photographs. I’d love to use another quote from Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith as a refrain for this first essay. I’d love to find a refrain focused on Cindy Hyde-Smith’s restless approach to poverty, her innovative ideas for equitable education, her commitment to eradicating state sanctioned premature death in Mississippi. But those quotes do not exist.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

What does exist, in all its grossness, is Cindy Hyde-Smith’s lack of home-training and her callous commitment to keep Mississippi contemptible on its promise to our children. Cindy Hyde-Smith is hoping that the worst of Mississippi punishes Mike Espy for daring to become the first Black senator in the Blackest state in the union in 150 years.

Mike Espy and I are not politically aligned. But Mike Espy has far more political courage than I will ever have. I talk it. I teach it. I write it. I make Mississippi art. As much as I love our state, I do not, as a Black man born and raised in Mississippi, have the courage nor the desire to become the first Black senator in Mississippi in over 150 years. There are many reasons for this cowardice. But the primary reason is that I long to outlive my mama and grandmama. This is far harder than it should be when we live and love in a state where, in 2018, nearly eight of ten white voters supported a senatorial candidate who said, in front of cameras, “If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.”

Despite what the rest of the nation believes about Mississippi, we know the range of our abundance. Cindy Hyde-Smith could have longed to be on the front of row of The Sonic Boom of the South, the front row of a reading by our Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winners, the front row of an exhibit at one of our prodigious museums, or the front row of a breathtaking play at our underfunded public schools. Cindy Hyde Smith, unprovoked, chose a public hanging in Mississippi as the site of her fandom. And, as quiet as it’s kept, Cindy Hyde-Smith won because she chose a public hanging in Mississippi as the site of her fandom.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

A few weeks ago, I was lucky enough to interview Moss Point, Mississippi, native Professor Eddie Glaude about his masterful exploration of James Baldwin’s life and work, Begin Again. To prepare for the interview, I went back and read the May 17, 1963, Time Magazine issue with Baldwin on the cover. In the left corner, right above the words “Birmingham and Beyond: The Negro’s Push for Equality” are the peculiarly spaced words “THIRTY CENTS.”

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

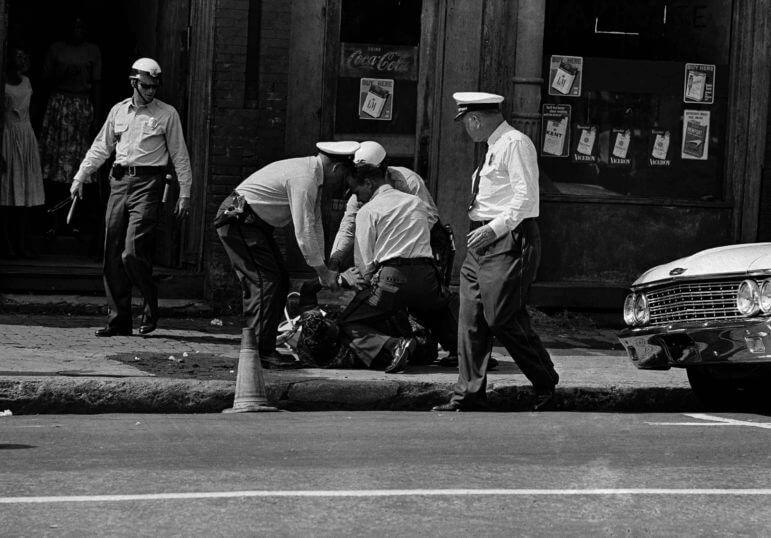

On page 24, near the top of a caption that reads, “Birmingham Cops Manhandling Negro Woman,” there is a photograph of two white officers watching three white officers assault a Black woman on the ground. One officer is grabbing the woman’s arm. One officer is restraining the woman’s legs. One officer has his knee in the woman’s neck. There is a Coca Cola poster above a cigarette sign on the door behind her. The woman is fighting from her back. She is fighting the officer with a knee on her neck. She is fighting the officer holding her arms. She is fighting the officer restraining her legs. She is fighting the officers watching. She is fighting all the folks who long to be on the front row of this orchestrated brutality. She is fighting all the folks scared to intervene.

Five white men. Plenty of politicians. Millions of eventual onlookers. One deeply southern Black woman, fighting for her life, and our dignity. This happened in Alabama. This happened in Mississippi. Fifty-seven years later, this happens in America.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

At the beginning of the interview with Eddie, I asked him why James Baldwin, a renowned Harlemite who, at that point, had never stepped foot in Mississippi or the deep south, could say, “I was going to be a writer, God, Satan and Mississippi notwithstanding.”

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

At the end of the interview, I asked Eddie if there is anything Mississippi specifically needs to reach its promise that the United States does not need. Eddie took my question seriously, or he acted as if he was taking my question seriously as all courageous Mississippians with good home-training do. Through glassy eyes and informed sincerity, Eddie said, “If Mississippi figures this out, we’ve solved the riddle of the Sphinx. That’s it. From the depth of our poverty to the brilliance of our culture, if we respond, we unlock it all.”

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

As much as Mississippi has been punished and locked by the brutalizing politics of Bilbo, Barnett, Stennis, Reeves and Cindy Hyde-Smith, it has been unlocked by the direct action of Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Medgar Evers, SNCC, Mamie Till, Emmett Till, and this current group of young Mississippians who will never stop fighting for Mississippi, and the nation’s, promise.

Like Eddie, these locksmiths know we can unlock it all here in Mississippi. They know we can be honest about what we’re unlocking. They know we must tell the truth about who benefits from Mississippi being, and being seen as, an impenetrable island of inequity. Who bruises here? Who blushes while eating the bruised? Who, and what, should actually be grateful in Mississippi?

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

In a piece called, “Since 1619,” my mother’s mentor, Margaret Walker Alexander, asked the question, “How long have I been living in hell for heaven?” Margaret Walker Alexander taught us that artistry without rigorous introspection and radical empathy is empty. I am trying to put myself in Cindy Hyde-Smith’s place. This is hard because while Black men and boys were the vast majority of folks publicly hanged in Mississippi, Black women were also publicly hanged. White men were publicly hanged. Indigenous men were publicly hanged. Yet there is no record of a white woman being publicly hanged in the state of Mississippi.

Still, if he invited me to a public hanging in Mississippi, what would I do? I know I would not be on the front row. I would likely be one of the Black Mississippians hanged, possibly for writing what should not be written, possibly for walking where I should not be walking. Mike Espy would be hanged, too, for daring to politically unlock Mississippi in the face of concerted brutality. Piss would dribble down the front of our thighs, behind our knees, off the tips of our toes into abundant Choctaw or Chickasaw land that the worst of Mississippi disfigures and depletes. Before the platform on which we were standing was taken away, I want to believe we could make eye contact with Cindy Hyde-Smith and all those loving Mississippians longing to be on the front row of a public hanging. If slack faced terror had not taken our tongues — and even if slack faced terror had — I would like to believe Mike Espy and I would mouth, “You will not win. You do not have to be this way. Mississippi is the key. We.”

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

Whether standing, marching, floating from trees, or fighting from our backs, I hope we continue the courageous work of unlocking Mississippi’s abundance today, tomorrow, forever. If we cease to unlock Mississippi’s abundance, I hope we have enough home-training to be honest about our unrivaled commitment to the death, destruction, and dishonor of our children.

How long have we been living in hell for heaven?

We will win. It is true. We will win. Eddie is right. Mississippi is the key. Margaret Walker is right. We must never cease to imagine. We must never forget. We must accept that we can always choose the most courageous, the most equitable, the most graceful, the absolute best of Mississippi. We can stop choosing torture, death, anguish, the spectacle of real anti-black violence when Mississippi looks us in the face. We have a choice. We’ve had a choice. We cannot love Mississippi and accept Cindy Hyde-Smith as a senator of the Blackest, most abundant state in this nation. We do not have to be this way.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

If he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.

I hate italics.

Editor’s Note: We are sharing our platform with Mississippians to write essays about race. This essay is the first in the series. Click here to read our extended editor’s note about this decision.

About the Author: Kiese Laymon, a Black Southern writer born and raised in Jackson, is the Hubert McAlexander Chair of English at the University of Mississippi. He is the author of three books, including the reissued How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America which will be released in November.

Want to hear more from Kiese? Join our exclusive event:

The post The Front Row appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Mississippi Marketplace: data center ups and downs, alcohol shortages and new manufacturing projects - February 19, 2026

- More Mississippi students are graduating despite pandemic-era disruptions, new data shows - February 19, 2026

- Education advocates says Mississippi needs honest, nuanced school choice discussion - February 19, 2026