Michelle Hodges-Feek hasn’t opened the box in her living room that arrived weeks ago from Mississippi.

She can’t bring herself to because inside are the cremated remains of her 40-year-old son, Daniel Hollan, who died Sept. 10 at a privately-run prison in the Mississippi Delta, hundreds of miles away.

She didn’t get an opportunity to say goodbye. Months later, she has an official cause of death and a certificate, but she’s still left with questions: What happened? How or why did this happen? Who is responsible?

“Nobody cares that my son died except me, and all I got is a big box that I don’t have the guts to open yet,” Hodges-Feek, who lives outside of Kansas City, Kansas, said as she began to cry.

One day she hopes to take a trip to Colorado, where their family previously lived, to have a memorial service for Hollan and spread his ashes.

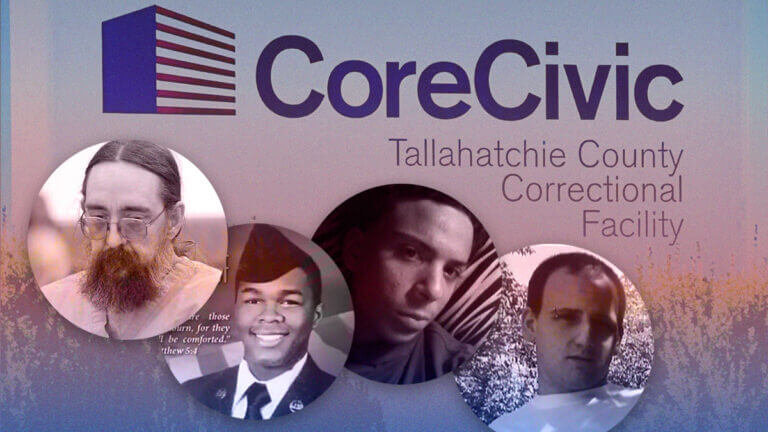

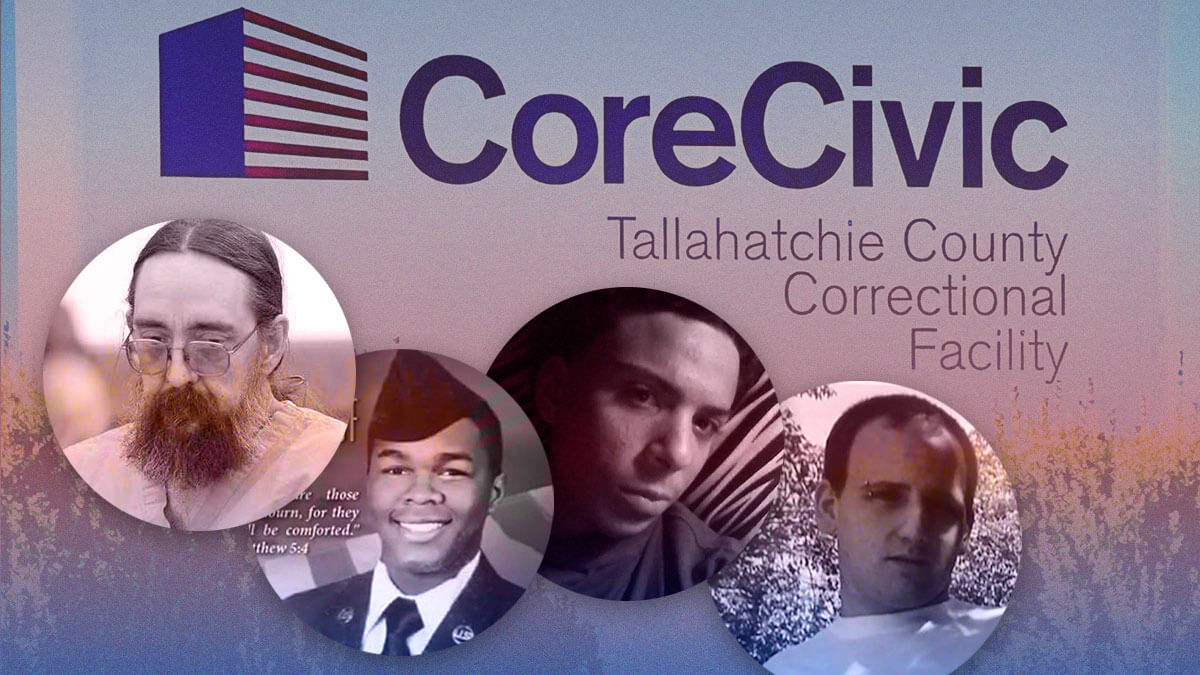

He is among at least five people who were from out of state or from outside the county who died in the last 1 1/2 years inside the Tallahatchie County Correctional Facility, a private prison operated by CoreCivic. Deaths there have left family members, like Hodges-Feek, uncertain about whom to go to for answers and whom to hold accountable.

Hollan was convicted in Montana in 2017 and spent time in state and privately run prisons there before arriving in Mississippi in January among the first group of Montana prisoners at Tallahatchie Correctional.

His mother sought answers and details from Mississippi and Montana prison officials, a county coroner and CoreCivic.

It took a month for her to learn he died from an accidental drug overdose. Hollan had struggled with addiction before, but his mother believes he may have used drugs in prison to self-medicate. He had lived with chronic arthritis that affected his skin and joints and a more recent heart condition.

To date, CoreCivic has contracted with four states, three counties, one U.S. territory and the U.S. Marshals Service to house people at the 2,672-bed Tallahatchie prison.

CoreCivic also signed a deal in February with Immigration and Customs Enforcement to expand immigration detention, including the use of 252 beds at the Tallahatchie facility.

The facility houses detainees awaiting trial and the convicted, some serving up to life. CoreCivic confirmed that pretrial detainees are housed separately from prisoners from state or federal agencies, but did not provide numbers of pretrial detainees and state prisoners.

In the industry of incarceration, CoreCivic is one of the two largest private prison companies in the United States, operating more than 70 facilities. The Tennessee-based company reported quarterly earnings this month of $580.4 million, up from 18.1% from the prior year quarter. Tallahatchie Correctional is located in the small town of Tutwiler with a population of 1,635 – a fraction of the prison’s capacity.

‘Is nobody responsible for these guys’ care?’

Hollan had never been to Mississippi, and it was not his decision to come. Montana prison officials, grappling with its prison population and needing to make upgrades to its main state facility, made the decision for him and 239 other prisoners when it signed a contract with CoreCivic. The state retained custody of him from hundreds of miles away.

Three years earlier, the Montana Board of Pardons and Parole ruled Hollan was not eligible for early release and needed to take a class. As he learned about his out-of-state transfer in 2025, he heard that the Arizona CoreCivic facility where Montana had already sent people offered the class he hoped to take to become eligible for parole, his mother said.

By June of this year, Hollan was up for administrative parole review, but the board informed him by letter he was ineligible for early release again because he didn’t fulfill the class requirement. The board holds hearings and reviews for incarcerated people housed in Montana for state-owned facilities, as well as for those held out of state in private facilities like Tallahatchie Correctional.

Hodges-Feek and her daughter, Rebecca McQuarrie, kept in touch with Hollan through several 5-minute weekly calls provided to prisoners. He shared that he had been trying to access medical care from the prison’s in-house staff for at least four months before his death.

“Is it Montana people who are watching them? Is it Montana people who are the guards? It’s CoreCivic’s people who are the guards,” Hodges-Feek said. “How can they pass the buck, is that legal? Is nobody responsible for these guys’ care?”

In response, a CoreCivic spokesperson Brian Todd said the company is deeply saddened by the death of any person in its care, and that the company is serious about following standards and policies that its government partners expect.

When someone dies, CoreCivic notifies the deceased’s home state and local law enforcement to conduct an investigation, Todd said. Then someone from Tallahatchie Correctional contacts the emergency contact listed in the prisoner or detainee’s file.

“Every death is investigated thoroughly and transparently, but it’s important to note that the circumstances of each incident will dictate how the investigation is handled,” he said in a Thursday statement. “Our focus remains on doing everything possible to prevent these events from happening in the first place through training, oversight and continuous improvement in our standard of care.”

Montana prisons spokesperson Alexandria Klapmeier wrote in an email that the Tutwiler Police Department investigated Hollan’s death and the Tallahatchie County Coroner’s Office was responsible for the death investigation.

Anthony Hawkins, the Tallahatchie coroner, confirmed he handles death investigations from the private prison, including that of Hollan and others sent from out of state or other Mississippi counties. After initially agreeing to speak, he has been unavailable for comment.

Tutwiler Police Chief Carlos Thompson was unavailable for comment about the status of the prison-death investigations.

Hodges-Feek was told Hollan was found in his cell, blue in the face in the morning, multiple hours after he was last seen or heard from the previous day. She wonders if his cellmate or others had seen anything.

She also submitted a public records request with the Montana Department of Corrections seeking copies of Hollan’s medical requests and related grievances. As of November, she is still waiting to receive those records.

The Montana prison official who informed Hodges-Feek and his sister about Hollan’s death said it didn’t appear to be suicide, the women said. McQuarrie wanted confirmation because the youngest of her three brothers died from suicide in 2017 and she didn’t think her mother could handle losing another child that way.

The state where a suspicious death occurs in a correctional facility outside Montana handles the investigation following that state’s legal processes and laws, Klapmeier said. Once the coroner finishes a death investigation, that official shares the information with the contract prison department and medical and investigation staff, she said.

Mississippi’s State Medical Examiner’s Office conducts the autopsies, as required by law for people who die in public or privately run prisons, jails or correctional facilities. The examination is used to help complete a death certificate, which is issued by the state Department of Health.

That office completed Hollan’s autopsy and those of the Vermont prisoners and Hinds County detainees, said Bailey Martin, spokesperson for the Department of Public Safety, which oversees the medical examiner’s office.

Mitzi Magleby is an advocate who has worked with incarcerated people and their families in Mississippi’s state- and privately run prisons. Whenever anyone dies in prison, she said the priority should be informing families and guiding them through processes.

“To me it’s a communication breakdown,” she said. “There’s not enough communication with these families. They’re in the dark.”

For out-of-state families like Hodges-Feek, Magleby said having to seek information from two state prison agencies and a private company is even more red tape to navigate.

Klapmeier, the Montana prison spokesperson, said the state pays to bring the body of the deceased to their family’s choice of funeral home in the state or transport their cremation remains to the family.

This was not made clear to Hodges-Feek. She said as her family considered the cost of bringing Hollan’s body home, her daughter and son-in-law considered taking out a loan to pay for it, but Hodges-Feek said she didn’t want them to take on that financial burden. Instead, she approved Hollan’s cremation in Mississippi.

Cremation felt like the only option to get her son home because it wasn’t clear where he would have been buried – Montana or Mississippi – if she pursued that option.

‘The safest and most dignified option’

Two men from Vermont, which also contracts with CoreCivic, also died in the Tallahatchie facility.

At the end of February 2024, 71-year-old Alfred Brochu, who was serving life for murder, was found unresponsive in his cell and taken to a hospital where he died. He had been at Tallahatchie Correctional since 2011, Vermont media reported.

Two weeks later in March, 43-year-old Sean Osterhout died. He came to Mississippi in 2019 and was serving up to a 30-year sentence for two charges of lewd and lascivious conduct with a child.

The Vermont Department of Corrections handled the death investigations and found that the deaths were not suspicious, said Haley Sommer, a department spokesperson for the Vermont Department of Corrections.

When a death of one of its people occurs at Tallahatchie Correctional, Vermont prison staff travel to the facility to look at circumstances that lead to the death and to consult with the medical team in Vermont about medical records, she said. From there, Vermont’s Defender General’s office has discretion of whether to conduct an investigation into a prison death.

Vermont has faced a challenge with space in its correctional facilities, and the state’s preference has been to send people out of state to reduce overcrowding at home, Sommer said.

The state has contracted with CoreCivic since 2018, and Vermont has found that contracts with private companies like CoreCivic to be useful because the state is able to maintain custody, which includes making decisions about inmates’ medical care.

“It is the safest and most dignified option,” Sommer said about sending inmates out of state to Mississippi and other prison facilities.

Months before Hollan’s death, Hinds County detainees Ulysses Nelson III and Christian Dyre, both 24, died within days of each other in the Tallahatchie facility.

Dyre had been at Tallahatchie Correctional since October 2023 and was facing a murder charge, and Nelson had been at the prison since January awaiting trial for aggravated assault, domestic violence and rape, Hinds County Sheriff Tyree Jones said.

Jones said their deaths were believed to be drug-related because there were reports of contraband in the zone where they both were housed. He said at the time that Tutwiler police would investigate and the State Medical Examiner’s Office would conduct an autopsy and toxicology reports.

Todd, the CoreCivic spokesman, said there is a zero-tolerance policy for anyone to introduce contraband into its facilities. The company seeks to prevent contraband from coming through such measures as searches, patrols, monitoring systems and mail checks, he said.

Tallahatchie Correctional medical staff immediately respond to emergency calls and are equipped to provide lifesaving care such as the administration of naloxone, which is an opioid-overdose reversing drug, he said.

Mississippi Today requested records about the men’s cause of death, but the information was not available by publication.

In an October interview, Jones would not comment about the sheriff’s office’s working relationship with operators of the Tallahatchie facility, citing ongoing litigation around the Hinds County Detention Center.

In 2023, the county signed a two-year contract with CoreCivic to send detainees to the private prison due to limited staff and conditions of a housing pod that has been closed down.

‘Nobody cares about these boys once they get locked up’

In the weeks after his death, Hodges-Feeks joined a Facebook group with other family members with loved ones in CoreCivic facilities in Mississippi and Arizona, including those who died there. She now knows she is not alone.

With questions still unanswered about her son’s death, Hodges-Feek and Hollan’s sister try to remember him as a person who put others first and had a good work ethic. When tornado sirens went off, Hollan was often the first to react and tell his family to get to a safe place. As a child, he saved his own money to buy a video game console.

But Hollan also had a knack for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. This, his mother said, paired with the death of his younger brother led him to turn to drugs and alcohol, and actions stemming from their use led to prison time, his mother said.

After completing an earlier sentence, Hollan tried to get a fresh start in Montana. Instead, he began to use drugs again, which Hodges-Feek said contributed to another prison charge. Hollan was convicted in 2017 of prostitution and received a 99-year sentence with 75 years suspended, according to court records.

Hodges-Feek kept in contact with her son over the years as he was moved to state-owned and private prisons in Montana.

In Mississippi, Hollan used his free weekly calls to tell his mother and sister what he was experiencing: How January rain caused flooding in the prison and the summer passed without air conditioning.

Hodges-Feek has seen how her older son, who also served time in prison, was able to turn his life around. She wonders what could have happened if Hollan had received a similar chance.

“(Daniel) never got the opportunity,” she said. “Nobody cares about those boys once they get locked up.”

- Former Greenwood police officer pleads guilty to federal drug trafficking charges - February 27, 2026

- UMMC officials say normal operations will resume Monday after cyberattack - February 27, 2026

- Hinds County public defender: Office needs additional funding to avert constitutional crisis - February 27, 2026