Just four doors down from the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument in west Jackson, a tangled mass of bushes, trees and vines obscure a house with a caved-in roof at 2300 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive.

Inside the only room left standing, pieces of plaster and foam insulation cover the sunken floor. A radio, an ornate console table and floor-length drapes, still hanging behind steel-frame windows, are the sole indications that someone once cared for this place.

In August, the storied home will go up for auction for the 7th year in a row because of unpaid taxes – joining thousands of properties across Jackson stuck in a complicated loop and for which no one claims responsibility.

Nearly 30 years ago, the home’s original owner, a fashionable woman named Arthurine Wansley, impressed her neighbors with the upgrades she’d made to the ranch-style home, recalled Lee Davis, a retired hospital environmental service technician who lives next door. Ceiling fans, wood-paneled walls and a cheerful lime green facade.

“Anybody would want to have a house like that,” Davis, 69, said.

But ever since Wansley developed dementia and her relatives moved her to California in the early 2000s, Davis bore witness as the home fell into dereliction. Wansley, who is still listed as the property’s owner in county records, died nearly 20 years ago. When the waist-high grass started to encroach on his lawn, Davis called the city of Jackson for help.

Then one day a few months ago, Davis noticed a for-sale sign outside the house. It was red, white and blue and said “Best Properties.” So Davis dialed the number on the sign to ask if they were going to cut the grass.

No, the woman who answered said – though the investment company she represented, also known as Viking Investments, is indeed selling the property for $2,500.

“They said they don’t do that, it’s the city’s responsibility,” Davis said.

2300 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive had been sold for unpaid taxes. But that doesn’t mean the government can force the investor to clean it up.

When a property owner doesn’t pay taxes, Mississippi counties hold an auction called a tax sale. The goal is to collect much-needed local revenue.

But in Jackson, where thousands of parcels go to auction each year, properties stuck in a tax sale loop year after year perpetuate blight. The bidders are often not prospective homeowners but investors who seek to profit from collecting interest on the unpaid taxes.

The scope of the problem is hard to quantify. To complicate matters, when investors come to own the properties they’ve bid on, there is no legal obligation for them to secure the property in their name. The outdated recordkeeping keeps the city of Jackson from knowing who owns these properties, impeding code enforcement efforts.

Investors also don’t have to pay the taxes, punting the property back to a tax sale.

“We’re a lien investment company. We’re not really wanting to acquire property,” said Nick Miller, the owner of Viking, which is based in downtown Jackson. “That’s a byproduct of investing in the tax liens.”

Viking has not paid taxes on 2300 since it acquired the property. So unless someone bids on it during this year’s tax sale in August, it will fall to the state.

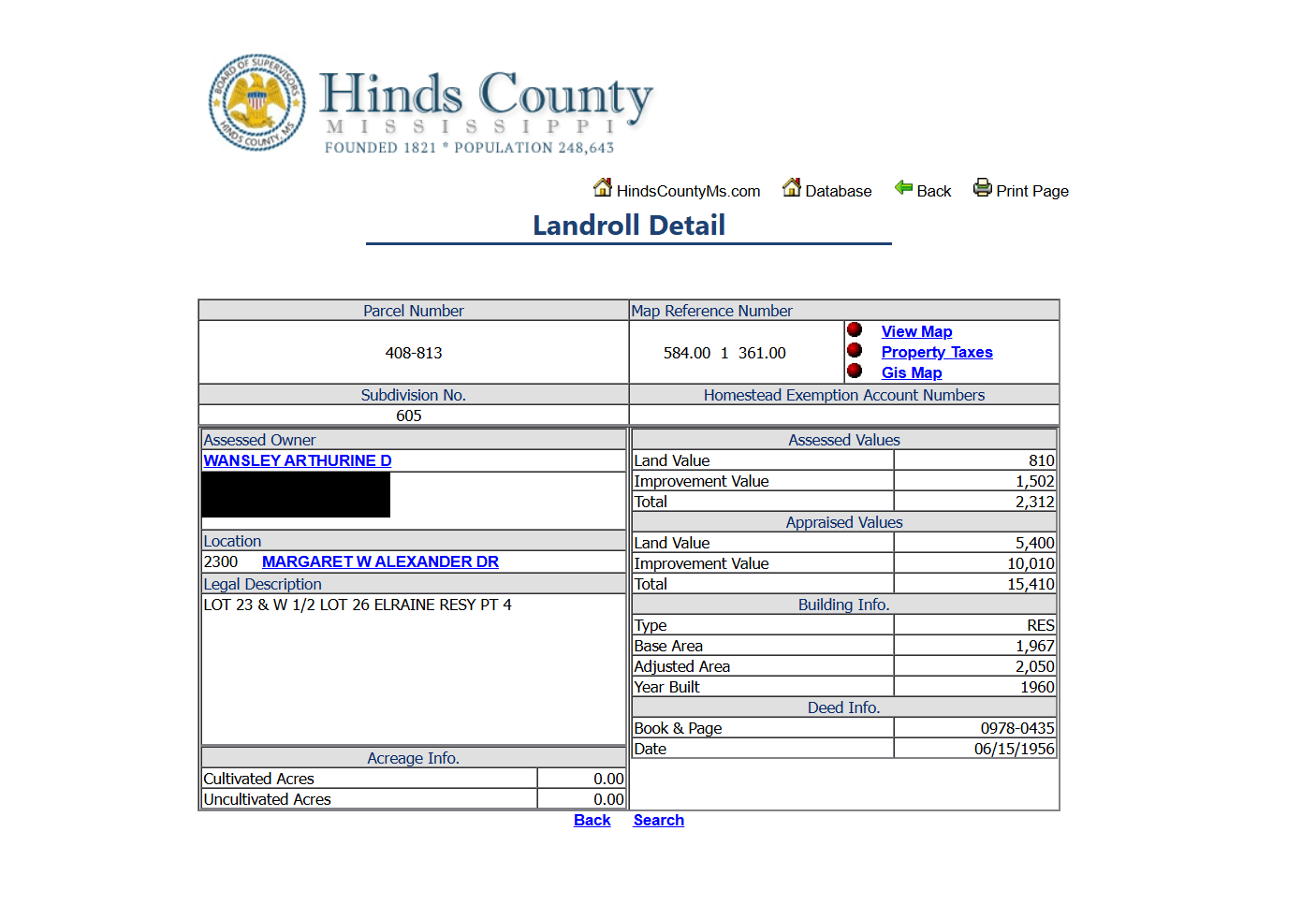

The government, then, will be responsible for cleaning it up. To work on a property, the city must send notices to whoever is listed as the owner on the Hinds County landroll.

For two years after Jackson opened a code enforcement case on 2300, Jackson sent repeated notices to Wansley’s last known address in California — even though she was not living and lost the home at the 2021 tax sale.

“You just found the perfect storm,” said Bill Chaney, an assistant secretary of state who oversees tax-forfeited properties that do not sell at auction. “This is an indication of all the cracks in the system.”

Outdated records leave properties dangling

2300 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive went up for auction in the fall of 2019 after someone in Wansley’s family failed to pay the initial $1,764 tax bill, according to Hinds County records. Despite repeated attempts, Mississippi Today could not reach any of Wansley’s relatives in California.

Over the next several years, a series of investment companies – some local, some not – bid on the unpaid taxes: GSRAN-Z LLC, Quicksilver Tax Funding LLC, College Investment Co., and FIG 20 LLC. None of these companies responded to Mississippi Today’s inquiries.

In what’s called the “redemption period,” Wansley’s family had two years to pay the overdue taxes. When that didn’t happen, her property became leverage. The winning bidders gained an opportunity to take her home through a document called a tax deed, which according to state law is “a perfect title with the immediate right of possession to the land sold for taxes.”

But none of the companies filed the tax deed with the Hinds County Chancery Clerk, likely because they could not find anyone to buy it and they did not want to become responsible for the condition of Wansley’s home.

The practice is common. There is no legal requirement to file the tax deed, nor is there a financial incentive. These companies often operate on slim margins, and the tax deed costs money. Plus, they may not want to end up like Wansley – listed as the owner of properties they aren’t responsible for.

“Are we going to be on that landroll record for the next 15 years until they update the record?” Miller said.

Chancery clerks need a deed to update a county’s landrolls, according to Lakeysia Liddell, the manager of Hinds County land division. So when companies don’t file a tax deed, the number of blighted properties in Jackson owned by tax investors remains unknown. People who lost their homes because of unpaid taxes continue to receive notices.

“They come in trying to pay those taxes thinking they can keep their property even though the redemption period has expired,” Liddell said.

Jackson’s code enforcement officers also rely on the landroll to send notices to property owners in violation. Robert Brunson, Jackson’s code enforcement manager, said that ideally, the city would take these companies to environmental court, where a judge can levy fines and even criminal penalties for dilapidated properties like 2300.

That accountability can’t happen if the city doesn’t know who the owner is. Brunson said Viking will come to environmental court if they have an interest in the property, because the city can use county records to find out if that is the case. But that doesn’t always happen: Viking is not listed as an one of the “interested parties” on the code violation notice for 2300.

“This is a business deal to them, to make money off the city of Jackson, off of Hinds County, really,” Brunson said. “We need more teeth, to be honest with you.”

To keep the chain of title clear, the companies will file the tax deed if they find a buyer for the property. But they may just let the property fall back to the tax sale to be dealt with by someone else.

Viking, which also hasn’t filed a tax deed for 2300, acquired the home in 2024 after the last bidder – the Jacksonville, Florida-based FIG 20 LLC – transferred its interest in the property to a Viking affiliate called SDG 20, according to a quitclaim deed filed in Hinds County.

Miller declined to say how much SDG paid FIG for the properties, but all told, he estimates he has sunk about $2,000 into the property on Margaret Walker Alexander Drive. If he sells it, he will make a couple hundred dollars.

The tax sale gamble

Miller, a Jackson resident, views his job as something of a public service, because his bids on Mississippians’ unpaid taxes help fund county services like libraries or police.

Spread across hundreds of parcels a year in Hinds County – thousands across the state – Miller can make a profit. His goal is not to get property, but to make money off the financial penalties owed by the original owner, including 1.5% monthly interest on the unpaid taxes.

When that doesn’t happen, and Miller becomes the owner, it’s as if he lost the bet. Acquiring blighted property is just a risk of the game; the gamble then becomes whether Viking can sell it.

“You’re looking at just returning your investment with interest,” said Andy Hammond, a Young, Wells, Williams attorney who Miller occasionally consults. “You can’t expect to actually get property. That just ends up happening.”

The seemingly accidental way Miller comes to own property in Jackson is why he’s frustrated when Viking is blamed for the city’s blight, which existed before he bid on unpaid taxes.

“How are we the problem if we’re willing to take a risk and invest $2 million in Hinds County a year?” Miller said.

Of course, when Miller acquires a property, he does not usually pay the next year’s taxes, so any property purchase from Viking would also likely come with a hefty tax bill.

If the city wants to hold tax sale investors more accountable for the condition of the properties they own, Mississippi’s tax sale laws need to be changed, according to Miller, Hammond and Sam Martin, a lobbyist who is helping them form a tax lien investor association.

“That gets you to the pickle that all of this has created,” Hammond said. “You have a city that wants certain things done but a law that disincentivizes the tax sale purchaser from doing anything.”

Hammond and his associates said they don’t know yet what the solution is, but one possible idea is to make it easier for the investor to clear title to his or her tax-forfeited properties.

Original owners who’ve lost their homes through tax sales can often get their property back if they can hire an attorney and go to court, especially if they didn’t receive a warning they could lose their property.

The tax sale buyer will lose the money they’ve put into improving the property, Hammond said. That risk means Viking will not work on its properties without going through a court process called a title confirmation suit.

“Let’s say we go in there without confirming the title first and we fix it up and we clean it up,” Miller said. “What do you think is going to happen? That homeowner is going to have a renewed interest in that property.”

But some in government say these investors should be made to take more responsibility for their properties. Last year, the Legislature considered but did not pass a bill that would have required people who gain properties through the tax sale to file the tax deed within 90 days or else cede their interest to the state.

Chaney, from the Secretary of State’s office, said Viking’s defense that it hasn’t confirmed the titles to its properties is tantamount to “legalese for ‘I don’t want to clean it up.’ ‘We own it, but we don’t really own it.’ Well, trust me, they’ll sell it in a heartbeat.”

That’s if they can find a buyer. Most of the time, the properties that Miller’s companies come to own are as blighted as 2300 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive.

2300 over time:

2014

2019

2022

“This property right here is a prime example of what mostly matures to us,” Miller said. “People walk away from it because they don’t want to deal with it.”

Neither does Miller. But he said cleaning it up could be worth it to someone, if they can afford it.

“The neighbor could buy it for $2,500 if he wanted to tear it down and clean it up,” Miller said.

Blight on historic block

If someone wanted to buy 2300 Margaret Walker Alexander Drive, they might look through public records to determine who owns the home – a common process for people who dabble in tax-forfeited parcels called a “title search.”

That search would end at a piece of paper 435 pages into a thick, leather-bound book on the second floor of the Hinds County Chancery Clerk’s Office. This is the proof of ownership that Arthurine Wansley and her husband, Louis Wade Wansley, received when they bought the home in 1956, on a block known back then as Guynes Street.

With three bedrooms, a carport, and central air and heat, it’s likely the house was built just for them. The Lanier High School graduates had joined a special community, the first-of-its-kind in Mississippi: A subdivision built by Black entrepreneurs for Black middle class families.

At that time, the housing options for Black Jacksonians were subpar and relegated to undesirable parts of the city.

“That community, that stability, that landownership, that power would have been really important,” said Robby Luckett, director of Jackson State University’s Margaret Walker Center.

A teacher in Jackson Public Schools, Arthurine Wansley played bridge with Margaret Walker Alexander, the acclaimed writer after whom the street is now named. She helped run neighborhood Spade and Fork Garden club with Myrlie Evers, the wife of civil rights icon Medgar Evers.

The families on the block were known for looking after each other’s kids and trading cucumbers and tomatoes they’d grown in their backyards. Wansley’s grandnephew, Michael Wade Wansley, grew up visiting 2300 for parties or holiday celebrations, when residents competed for the best Christmas decorations.

“We didn’t even think about it being a historic block when I was growing up,” he said. “We just knew that Dr. Margaret Walker Alexander lived on that block. George Harmon lived on that block. He owned Harmon’s Drug Store on Farish Street. So it was, I mean, everybody over there was either involved in politics or educated.”

But the tight-knit community ended on the corner of Ridgeway Street, where a working-class white neighborhood began, said Keena Graham, the superintendent of the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home National Monument.

“You’re having a great time on this street, but you don’t go over too much, too far afield,” Graham said. “Two streets over, that’s dangerous.”

Much of that history is recounted in a 2013 application to include the Medgar Evers Historic District — which encompasses Margaret Walker Alexander Drive — on the National Register of Historic Places.

As an original home to the block, 2300 is covered by that designation. But that didn’t stop the home from falling into the tax sale loop.

“I knew it all of my life as a middle-class-type neighborhood,” said Frank Figgers, a member of Shady Grove M.B. Church just around the corner from 2300. “When that’s where your teachers lived, where your pharmacist lived, I just don’t think I’ll ever see it as blight.”

In search of a responsible party

Some family members of the original residents of Margaret Walker Alexander Drive still live in their homes. But the block today is mostly retirees like Davis, renter, and empty houses, surrounded by overgrown land, that are falling apart.

In neighborhoods like this, nonprofits, such one run by Jackson-area state Rep. Ronnie Crudup Jr, have used the tax sale to buy homes and rehabilitate them.

“I always tell people it’s good to have a good attorney on hand to do those title searches for you,” Crudup said.

More often, though, the tax sale loop creates a cycle of frustration.

When private individuals can’t or won’t fix up a property, the government must step in. The state owns more than 1,800 tax-forfeited properties in Jackson, according to data from the secretary of state — plots that no one wanted to buy at the tax sale auction.

“We got it in even worse condition than it was when it was in a bad condition,” Chaney said.

Brunson feels similarly. He has a handful of code enforcement officers for the entire city, but some Jacksonians complain his team is nowhere to be found.

“They won’t cut the grass, but they’ll sell it,” Brunson said of tax sale investors. “There should be a law against that, taking these people’s money, saying, ‘Oh well, you didn’t do your title search, thank you for $3,000 down.’”

But if the city started fining tax sale investors for the blight, Miller said some of them may stop bidding.

“People are going to drop out of the system,” Miller said. “If nobody is there to bid on these liens, what’s going to happen to the $19 million deficiency every year – struck to the state?”

It doesn’t seem likely anyone from Wansley’s family will save the property. Michael Wade Wansley, the grandnephew, is retired and lives in Pennsylvania. He said he doesn’t think he has any relatives left in Jackson. He wondered why Davis and his neighbors let the home deteriorate.

“I would think if people were still living over there they wouldn’t have let it go down to that level of poverty,” he said.

Barbara Walker, a retired teacher who lives directly across from 2300, used to go half and half with another neighbor to pay someone to cut the grass.

“To me, it was worth the investment,” she said. “I didn’t want the place looking as bad as it’s looking.”

When her neighbor moved away, Walker couldn’t afford the landscaping on her own. That’s when Davis started calling the city, hoping they’d cut the grass.

Informed that Miller said he could buy the property, Davis seemed puzzled.

“Who, me?” he said.

Every now and then, Davis will ask his lawn guy to mow a patch of grass by Viking’s for-sale sign. But until the overgrowth is addressed, Davis won’t let his 6-year-old granddaughter play outside when she comes to visit. He’s killed too many snakes in his yard.

In November, the city council declared the home a public nuisance, the first step to tear it down. Jackson will have to hire a company to do the demolition, which requires attaching a lien, or a debt that must be repaid, on the property. Whoever buys it next will have to repay that lien.

On a recent Tuesday, Davis looked at the pink and yellow notices – orders condemning the home – that Brunson pinned inside the decaying carport. When he opened the carport closet, he realized the water heater had been stolen. The only items left were glass Coca-Cola bottles, silver tinsel and a Santa Hat.

Walker said she hopes 2300 can become a park once the house is demolished: “It’s already tearing itself down.”

- Maybe competition can be good for Mississippi public schools, or at least for teacher pay - February 8, 2026

- Brad Arnold, lead singer of Mississippi-formed rock band 3 Doors Down, dies at 47 - February 7, 2026

- People in 15 counties can receive replacement SNAP benefits without application - February 6, 2026