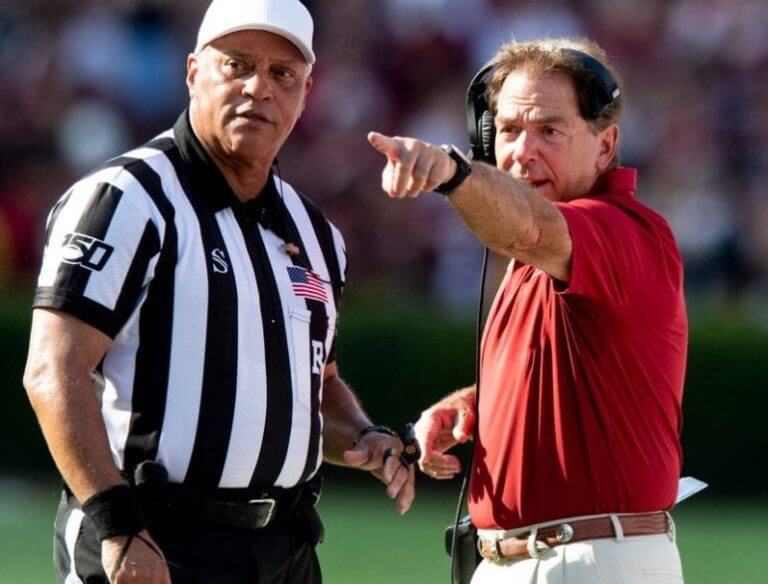

Courtesy of Hubert Owens

Hubert Owens, who earned the respect of SEC coaches, listens patiently as Nick Saban makes a point.

Trailblazing SEC football ref Hubert Owens wore the referee’s white cap, and it fit him perfectly

The Yazoo City native’s story is one worth telling.

By Rick Cleveland | Oct. 21, 2020

See the man with Nick Saban in the photo above? Recognize him? If you follow Southeastern Conference football, surely you do. In recent years he has played a huge role in many of the most important and most watched games in SEC history.

You may not know his name, but you know his face. You probably know his voice. He’s the guy in stripes who always wore the white cap, which differentiates the referee from the other officials. He’s the guy who blew the whistle to start the games. He’s the guy who stood back behind the quarterback, the guy who reached down around his belt and turned his microphone on so that he could tell 90,000 people and millions across the country who committed a penalty and how many yards it would cost his team.

In the storm of emotions that often is college football, he was the calm. He ran the show. Quite simply, he’s the guy who controlled the games until his retirement after the 2019 season.

He is 62-year-old Hubert Edward Owens and he grew up in Yazoo City, and his is a story worth telling.

Growing up in Yazoo – “half hills, half Delta, all crazy,” wrote Willie Morris, lovingly – Hubert Owens doesn’t remember when there wasn’t a ball around. Matter of fact, he doesn’t remember when there weren’t whistles, black and white striped shirts, and red handkerchiefs around, either. They belonged to his father, Hubert Roosevelt Owens, who officiated high school games and in the SWAC.

The father often took his sons to the games he worked. Big Hubert was an umpire, the guy who stands in the middle of the defensive secondary, just a few yards from the line of scrimmage. The umpire is the guy who most often calls holding penalties. When the umpire throws his flag, the offense usually groans. Big Hubert took his son to games in Lorman, Jackson, Grambling, Itta Bena and Baton Rouge, where the players, fans and the officials were nearly always all African-American.

But here’s the deal: On the Saturdays when little Hubert stayed home and turned the college games on the TV, many of the players were Black, but none of the officials were. One can only imagine the impression that must have left on a 10-year-old who loved sports as much as little Hubert did.

Over half a century later, Owens said, “I don’t know that I thought about it that much. To me, that’s just the way it was.”

Before integration, big Hubert officiated high school games in the old Magnolia High School Activities Association, which was no more after integration. When integration finally did come to Mississippi, the officials who had served the old Magnolia association had to file a court injunction to officiate in the integrated games Mississippi High School Activities Association.

That was only about 50 years ago.

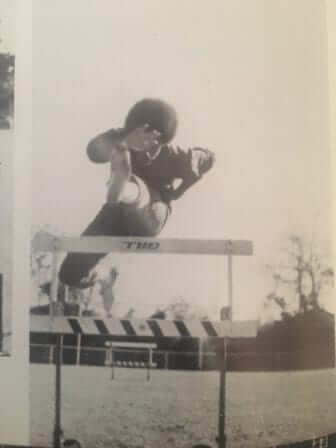

Before he was a referee, little Hubert Owens was an athlete. He played football and ran track at Yazoo High. Peter Boston, brother of the great Olympic hero Ralph Boston, was one of his coaches, the one who taught him the proper form to run the hurdles in track. Hubert finished third in the state in that event. His football hero in those days was Yazoo’s own Willie Brown, the great NFL cornerback, a Pro Football Hall of Famer. Like Willie Brown, Hubert was a defensive back, talented enough to earn a scholarship to Mississippi Valley State, where he was recruited by SWAC legend Davis Weathersby.

In fact, you will still find Hubert Owens in the MVSU and SWAC record books. In a SWAC game against Arkansas-Pine Bluff, Owens returned a blocked field goal 99 yards for a touchdown.

Upon graduation from MVSU, Owens tried pro football but found, “I just plain wasn’t good enough.”

Naturally, he became an official. Like father, like son.

The younger Hubert Owens officiated high school ball and eventually in the SWAC. At first he was a side judge, lining up behind the defense and mostly making calls that involve pass plays. He was a promising official on one of the SWAC’s top crews. Then, in 2002 something happened that changed the course of Owens’ officiating career. His crew was calling a game matching Prairie View and Texas Southern in the annual Labor Day Classic. Dr. Cassie “Cass” Pennington of Indianola was the crew chief, the referee.

“It was right before the game, and Dr. Pennington said he wasn’t feeling well and didn’t think he could do the game,” Owens said. “He looked right at me, took off the white hat and gave it to me.”

“You are the referee,” Pennington said.

And Hubert Owens became a referee for the rest of his career, a career that again drastically changed in the spring of 2005. That’s when Owens attended a officiating clinic in Beaumont, Texas, and ran into an official who told him he would soon be hearing from the SEC. “They want a Black referee and you are the only one on their list,” the man told him. And that’s exactly what happened.

For the football season of 2005, Owens became only the third African American referee in SEC history. In 2013, he became the first African American to serve as referee in the SEC Championship Game at the Georgia Dome in what had become his hometown, Atlanta. (Formerly Director of Contract Compliance for the City of Atlanta, Owens now works at Luster National, Inc. as National Supplier Diversity and Contract Compliance Director.)

Former SEC referee Steve Shaw – by then the director of SEC officials and now the NCAA National Coordinator of Officials – was the man who tabbed Owens to make SEC history.

“Hubert is a really good official, but what sets him apart is his game management,” Shaw said. “He’s in charge and everybody knows it although hardly ever had to raise his voice. That’s No. 1, No. 2 is the rapport he had with the coaches and the respect those coaches had for him. They would see Hubert and say ‘OK, we got Hubert’s crew today. We’ll be in good hands.’ In officiating, you can’t measure the value of that.”

Stan Murray, the former Mississippi State star player, served as a back judge on Owens’ crew for most of Owens’ 15 years in the SEC. They were the products of two different environments. Murray grew up going to mostly segregated schools in Jackson and following the SEC. For many of his formative years, Owens went to an all-Black school in Yazoo City and identified with what he knew, the SWAC. Much later in life, officiating brought them together in the SEC. The two became close friends and share a great mutual respect.

Said Murray, “Everyone on our crew had a nickname and this will tell you how much we thought of Hubert. His nickame was, ‘The Franchise.’”

Murray marvels at his friend’s serene manner in the most pressure-packed moments of officiating high level football, when bowl games, millions of dollars and coaches’ livelihoods hang in the balance.

“Unflappable,” Murray says of Owens. “The players, the fans, the coaches would all be going nuts and he never changed, no matter what.”

Shaw, who was one of college football’s most-respected referees before leaving the field, firmly believes Owens faced pressure he never faced himself.

“Hubert carried a burden I never had to carry because of who he was,” Shaw said. “Think about it. Because of his race, he was so recognizable. He was one of the very few people of his race doing what he was doing at the level he was doing it. It was like he had to be good every week. He had to prepare extra. He had to deliver because he was representing a lot of people. You better believe there were a lot of officials watching him to see how he did.

“That’s what makes his great career even more impressive to me. He had a lot of firsts in his career and he earned those. He was the first to do this and the first to do that, the first to run the show at an SEC Championship and he handled it incredibly well. He did some of the biggest bowl games incredibly well. He provided a great role model for younger African American offiicials.”

Asked if he felt what Shaw called “a burden,” Owens responded, “Well, I did feel like I was representing a whole lot more people than myself. First, I felt I was presenting my father and so many others like him who were never given the opportunities I had. That was a big responsibility, I thought. And then there was the responsibility I felt like I had to those who would come behind me. I wanted to show that I – and people who look like me – could handle the big stage. Looking back, I am proud of the many firsts I had.”

So, we’ve been through the firsts. It’s time to talk about the lasts. Owens said “I just knew” it was time to step away after the 2019 season. “Physically, it was time,” he said.

His last SEC game?

“It was the piss-and-miss game, the (2019) Egg Bowl,” Owens said, chuckling.

Said Shaw, “He handled that ending as well as it could be handled.”

It was not lost on Owens that his last game matched two schools from his home state that his father could not have attended, much less ever officiated one of their football games.

But it was his last bowl game that might mean the most to Owens. He had done several huge bowl games, including the Fiesta Bowl, during his career. Last year, Shaw assigned him the Celebration Bowl – SWAC champion Alcorn vs. MEAC champion North Carolina A&T – televised nationally by ABC. For that game, Shaw put together an all-star crew of all African American officials from the SEC and Sun Belt conferences.

“Of course, the referee had to be Hubert Owens,” Shaw said.

Said Owens, “For me with my background officiating in the SWAC and following in my dad’s footsteps, it felt like the the perfect ending.”

The post Trailblazing SEC football official Hubert Owens wore the referee’s white cap, and it fit him perfectly appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- UMMC clinic closures extend to Friday amid cyberattack recovery - February 25, 2026

- Regency Hospital in Meridian to close by mid-March - February 25, 2026

- Advocates call for funding, collaboration as more Mississippians are expected to struggle with food insecurity - February 25, 2026