Editor’s note: Mississippi Today Ideas is publishing guest essays from people impacted by Hurricane Katrina during the week of the 20th anniversary of the storm that hit the Mississippi Gulf Coast on Aug. 29, 2005.

I don’t have any really good Katrina stories to tell.

Thinking about Katrina, even 20 years later, still freaks me right the hell out.

Many people will be remembering the storm on Aug. 29. I promise you, I will be doing my best not to think about it. Katrina in one way or another consumed years of my adult life, personally and professionally.

Honestly, I wish I had not volunteered a few months back to write this column. But I did my job after Katrina, and I’ll do it now.

I was a reporter/editor for the Sun Herald in 2005, basically Capitol bureau chief covering the Legislature and state government, splitting time between Jackson, the Coast and Hattiesburg. I had recently moved from the Coast to Hattiesburg — for reasons I’ll get to later — and I spent much time burning up U.S. 49 going to and fro.

One of the clearest early recollections I still have of Katrina is being at the Sun Herald the day before, getting ready to head back to Hattiesburg with a couple of newspaper staffers who planned to ride it out at my house (Hattiesburg, as we and the National Guard soon discovered, wasn’t far enough away). Someone was going through the newsroom saying, “Hey, y’all, look at this.”

They had a copy of “The Bulletin,” as it’s now known. They said something like, “I think the National Weather Service is telling us to kiss our butts goodbye.”

The NWS bulletin, in all caps, said in part: “URGENT … DEVASTATING DAMAGE EXPECTED … MOST OF THE AREA WILL BE UNINHABITABLE FOR WEEKS PERHAPS LONGER … PERSONS PETS AND LIVESTOCK EXPOSED TO THE WINDS WILL FACE CERTAIN DEATH IF STRUCK … POWER OUTAGES WILL LAST FOR WEEKS … WATER SHORTAGES WILL MAKE HUMAN SUFFERING INCREDIBLE BY MODERN STANDARDS … DO NOT VENTURE OUTSIDE!”

Well, most of us had covered hurricanes before. Some longer-time staffers had been through many. And while we knew Katrina was going to be bad, we thought that NWS communique was downright weird, perhaps a bit too alarmist.

But it was prophetic.

Even 70 miles inland, Katrina was terrifying. But my memories of the actual storm have grown fuzzy. I do remember heading out well before dawn the next morning, trying to make it to Jackson in time for a helicopter sortie of state officials and media Gov. Haley Barbour had arranged to view the damage on the Coast. It took me forever to maneuver around trees across the highway or wait as crews cut paths. Early on, the radio news loop kept saying New Orleans had been spared major destruction.

But as the sun came up and I got closer to Jackson, new reports started coming in that Louisiana and New Orleans were hit hard, levees had been breached and New Orleans was seeing massive flooding.

My heart sank. At the time, I was as worried about the fate of New Orleans — particularly Ochsner Medical Center — as I was Mississippi.

My first wife, Jennifer, had at the time recently been placed on the heart transplant list at Ochsner. We were living in Hattiesburg to be near family who were helping and still be close enough to Ochsner to rush there when a donor heart became available.

The helicopter flight over the Coast that morning was surreal and horrifying. It looked like, as Gov. Barbour said that day, an atomic bomb had gone off, or the hand of God had wiped large swaths of the Coast away.

Communications after Katrina were crap. Cellphone service was worse than spotty, and I hadn’t been able to reach anyone or have a photographer on the flight with me. I shot photos with a point-and-shoot while white knuckled and leaning out the door of a Huey.

And not having talked with anyone at the Sun Herald, as we flew over the destruction, my mind raced: How many of my colleagues and friends died in this storm? How will the Coast ever recover from this? Did Ochsner hospital survive?

Back on the ground at an Air Guard base in Gulfport, I managed to borrow a satellite phone and talk with my boss at the Sun Herald. Most, but not all, employees had been accounted for, but they were still unable to get in touch with some in Bay St. Louis and Hancock County. It would be a few days before we learned that, miraculously, no newspaper employees had died in the storm, although at least one had family members who perished.

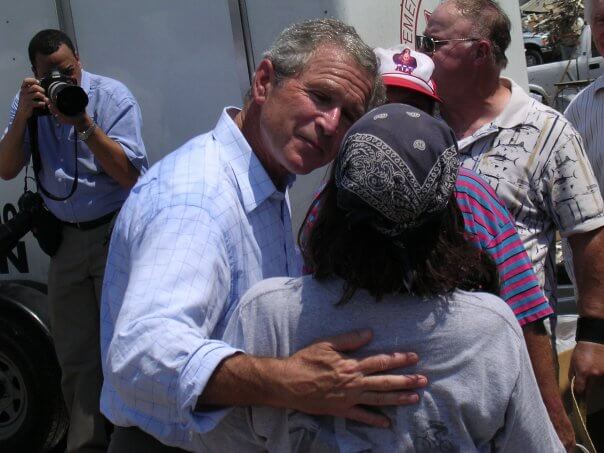

The first few months after the storm are kind of a blur to me now, other than we were very busy. I spent much of my time following Gov. Barbour from Jackson to the Coast to Washington, and at times following President George W. Bush and U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran and others as they tried to figure out a recovery plan and funding.

There were special legislative sessions. Big political fights. I had to spend about a month in D.C. watching Congress dicker over Katrina relief spending.

Ochsner wasn’t destroyed by Katrina, but it went into triage mode, and a lot of staff left. Its transplant unit technically kept running, but … not like normal. We had been assured pre-Katrina that the wait for a donor heart should be six months, tops.

One can’t just jump from one hospital’s transplant list to another. It doesn’t work that way. And you have to be within about two hours of a hospital. At the time, they weren’t doing heart transplants in Mississippi.

It took well over a year for Jennifer to get a heart, and she got sicker and sicker in the meantime, amidst Katrina’s aftermath.

She passed away, from an infection, about a month shy of a year after Katrina.

The official death count for Katrina was 1,833, including 238 in Mississippi. It caused $108 billion in damage, destroyed 104,000 housing units in Mississippi including 51,000 houses.

But those numbers don’t cover collateral damage, or all the anguish that storm caused. Those National Weather Service folks were right. The human suffering was incredible by modern standards.

I really intended to have a different focus with this column — perhaps tell a few journalism war stories, talk about the years-long recovery efforts, heck, maybe even try to write something more uplifting about Mississippians’ famous resiliency, how people “hitched up their britches” and got to work on recovery.

I remember a woman on the Coast at a town hall meeting some time well after the storm opined that she was sick and damned tired of being so resilient.

But as I sat to write this, I couldn’t really dredge up any good Katrina stories.

And I damned sure can’t think of anything good to say about that storm, other than all storms end, the sun eventually comes out and life goes on.

I’m afraid I just told a bad Katrina story, and I told it poorly. It’s one I haven’t told very often and I don’t intend to any more if I can help it. But I guess it’s my main Katrina story.

I try to forget that storm as much as possible, when not required to think about it for work. I’m ready for this “anniversary” to be over, and I hope my memories of it fade even more.

Katrina sucked.