GULFPORT – “This is an outdoors person’s state, you know what I’m saying?” Derrick Evans said of Mississippi on a muggy September evening at his office in Turkey Creek. “It’s agricultural, it’s fishing, it’s hunting.”

Yet, Evans said, political priorities in the state, named after the immense river to its west, seem detached from that very culture.

“A polluted stream, an environmental vulnerability, is actually an abrogation to what we might call the Southern way of life,” he said.

In 2023, a study concluded Mississippi was the most vulnerable state to climate change in the country. The research, done by the Environmental Defense Fund and Texas A&M University, quantified how a litany of social inequities exacerbate frequent natural disasters – such as flooding, tornadoes, hurricanes, heat and drought – not just in Mississippi but across the South.

Grace Tee Lewis, a Texas-based senior health scientist with EDF and one of the study’s authors, said the region’s history of segregation and underinvestment in public services comes back to bite it when a disaster hits. In a rural state that ranks near the bottom in health outcomes and access to care, for example, a hurricane is all the more likely to sever a sick person’s access to medicine.

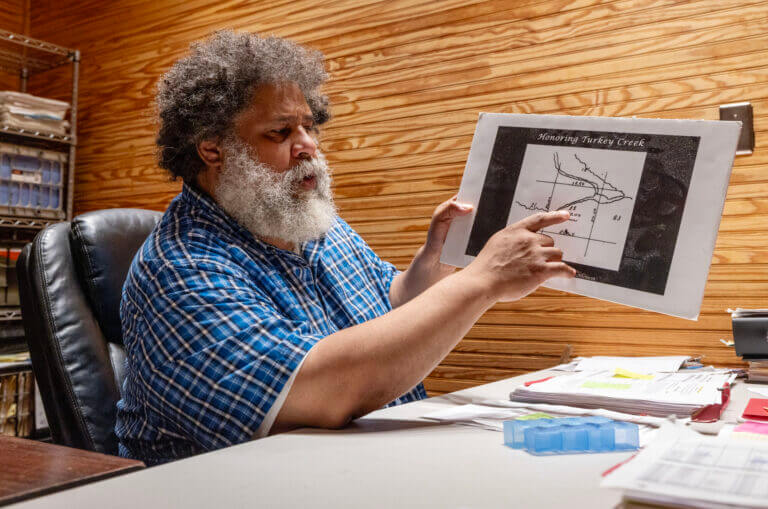

Derrick Evans, a community activist and resident of Turkey Creek, talks about the historic area in Gulfport, Miss., on Thursday, Sept. 18, 2025. Credit: Eric Shelton/Mississippi Today

“In the South, where you have historical policies that have created a lot of stratification in wealth and resources, I think that contributes to disparities in vulnerability,” Lewis said. “That extends itself to investments in climate – flood mitigation, hurricane preparedness. Often what we see in the Gulf is, they’re the same communities that are getting hit time and again.”

Lewis and her colleagues’ work echoes similar findings by the federal government. Both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Global Change Research Program published reports in recent years linking social disparities in the Southeast to a higher risk of impacts from natural disasters.

The study also said Turkey Creek, the historic Gulfport neighborhood founded by Evans’ ancestors and other freed slaves after the Civil War, sits in the fifth most vulnerable census tract out of over 73,000 in the United States.

As he walked outside his mother’s house, Evans pointed to just under the roof, showing where the water finally stopped after Hurricane Katrina landed in 2005. While surprised Turkey Creek ranked so highly, he was well aware of its environmental challenges.

The neighborhood’s settlers, he said, knew how to comport their lives with the surrounding watershed. They built their homes, for instance, on a ridge following the curvature of the surrounding streams. But especially after the city of Gulfport annexed the neighborhood in the 1990s, the watershed slowly devolved into pavement-laden developments.

A view of Turkey Creek in Gulfport, Miss., on Friday, Sept. 19, 2025. Credit: Eric Shelton/Mississippi Today

“Climate resiliency,” Evans proclaimed, “starts with not being ground zero to someone else’s future.”

Over the years, coastal developers and officials replaced wetlands, which naturally absorb water, with concrete slabs that repel flooding onto other property.

David Holt, coordinator of sustainability sciences at the University of Southern Mississippi, explained that coastal cities after Katrina began developing further inland, replacing forested or grassy areas with subdivisions. But in doing so, Holt said, they were “not really thinking about drainage.”

“We get a lot of localized flooding with these new developments,” he said.

Gulfport officials denied to Mississippi Today that commercialization has harmed the city’s drainage, adding they’ve improved stormwater management standards for new construction. But lifelong Coast residents, like Rose Green in Turkey Creek, said their ditches still regularly overflow, and fear their vulnerability to climate change will only grow without better planning.

“The water is going to back up,” Green said. “We’re going to get drowned out here.”

Rose Green prepares to give her thoughts on the issues with Turkey Creek in Gulfport, Miss., on Friday, Sept. 19, 2025. Credit: Eric Shelton/Mississippi Today

“We are all in a disaster area”

Leaders and scientists around the world agree greenhouse gas emissions from human activity are warming the planet, leading to more variability in climate trends and a spike in extreme natural disasters.

“The Southeast faces increasing intensity of climate change impacts including warming temperatures, extreme precipitation events, droughts, sea level rise, and tropical cyclones,” the Environmental Protection Agency says on its website.

In the last 10 years, according to federal weather data, storms in Mississippi caused an estimated $1 billion in property and crop damage. The data, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, directly link those events to 84 deaths and 608 injuries, and indirectly to 19 other deaths and 100 other injuries.

Half of Mississippi’s counties saw a direct or indirect death linked to a natural disaster in the last decade.

“ The reality is that we are all in a disaster area,” Holt said. “Every corner of this state can be hit by a natural disaster.”

In many ways, surviving and recovering from disasters comes down to wealth, both on a personal and communal level.

“Preparedness looks different for people who are low-income,” said Rhonda Rhodes, president of the Hancock Resource Center, which offers disaster counseling on the Coast. “They can’t just go get a hotel at whatever cost, so they’re stuck going to shelters, whether the storm gets here or not. They don’t get paid if they don’t work, they don’t have money for gas.

“It is a real crisis for families that are low-income to have to evacuate. So a lot of them don’t, which is its own problem.”

The nation’s poorest state, Mississippi is already feeling the financial impacts of climate change more than most states. In 2021, only three states – Louisiana, Florida and Oklahoma – had a higher financial burden than Mississippi paying for home insurance premiums, which have risen as insurers adjust for the risk of increased disasters.

Last year, amid rising temperatures, a third of Mississippians were unable to pay a recent energy bill, the highest rate in the country.

Over the summer, an Urban Institute study found that, based on average income, Mississippi would have the least fiscal capacity of any state to handle disasters should the Trump Administration follow through with plans to gut the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

“Should more disaster responsibility be pushed to the states, Mississippi would face some unique challenges relative to other states that have a broader set of reserves (for disaster funding),” Sara McTarnaghan, one of the study’s authors, said.

A scramble for mitigation funds

In recent years, governments at every level have shifted their focus to mitigation, or projects that better protect homes and infrastructure from natural disasters.

The Mississippi Emergency Management Agency is overseeing 160 local mitigation projects. Those include safe rooms and sirens to prepare for tornadoes, drainage upgrades to deter flooding, and backup generators for water systems.

But all of the state’s mitigation efforts are primarily funded with federal programs, and mainly through FEMA. The Trump administration cut one of the agency’s key mitigation programs – the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities fund, or BRIC – earlier this year. Moreover, the recent slew of cuts to EPA grants included $20 million set for a self-sustainable resiliency hub in Jackson.

For many small, rural areas, federal mitigation dollars are the only path toward funding local climate resilience. Beverly Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, said recent changes on the national level will disproportionately leave poorer communities in danger going forward.

“The cuts to FEMA are really devastating,” Wright said. “You really see bleak days ahead because Mother Nature is not backing off.”

In the Delta about 20 miles east of Clarksdale, officials in Marks are worried that flooding could contribute to the outmigration the small city’s seen over the last few decades.

“In the early spring, it was raining every day,” said Joe Shegog, the town’s former mayor who stepped down from office earlier this year. “A lot of people couldn’t get in or out of their homes unless they used a boat.”

Since 1980, Marks’ population dropped by over a third, Census data shows, from about 2,200 people to 1,400. The median household income is about $25,000 less than the rest of the state.

A combination of flash flooding and water from the Coldwater River – which local officials say has gotten worse because of seepage from the Arkabutla Lake north of Marks – has become a regular threat to residents as the city’s drainage infrastructure has aged.

A large swath of the city and its surrounding areas sit in “Zone A” of FEMA’s flood map, meaning they have high risk. As is the case with much of the Delta, flooding incapacitates Marks’ local farming, a key economic driver in the region and state as a whole. The EDF and Texas A&M study ranked Quitman County, where Marks is located, in the 98th percentile of climate vulnerability in the country.

Shegog, who served as either an alderman or mayor in Marks since 1987, said the city’s small tax base can’t fund needed infrastructure improvements. In 2023, Quitman County applied for $5 million from FEMA’s BRIC program to upgrade drainage pumps and shore up levees.

FEMA didn’t select the project, leading local officials to wonder if Marks just didn’t have enough property value to attract the spending. Velma Wilson, the county’s economic director, said the county planned to reapply before the federal government announced plans to cut the BRIC program in April.

Similarly, Shegog said it’s hard to attract attention from the state with a dwindling population.

“There’s not as many votes in these small areas,” he said.

“We can’t do this forever”

In 2024, 63% of American adults were worried about global warming, according to a Yale University poll. In Mississippi, that number was 55%.

What climate change will look like in the state isn’t a simple answer, explained Holt, the USM professor. While the conditions for hurricanes, for instance, have become more common as the ocean warms, increasing wind shear may also keep them from building and hitting land. What’s more clear, he said, is that the average storms are intensifying more rapidly and they’re coming during a wider span of the year.

“We’re supposed to be all nervous and worried in July and August, not October and November,” he said.

Another complicated trend, Holt explained, is that seemingly opposite extremes are each becoming more common: intense heat and ice storms, heavy rainfall and drought.

But while more of the public recognizes the threats of climate change, the language around the issue is still politicized, Holt said.

Train tracks on in the Turkey Creek area of Gulfport, Miss., on Friday, Sept. 19, 2025. Credit: Eric Shelton/Mississippi Today

“People want to say it’s not climate change, it’s just a natural cycle, or it’s all in God’s plan,” he said. “But the reality is, it doesn’t change anything.”

Holt argued that the economic effects of climate change may be the key to attract the attention of politicians and other decision-makers in Mississippi: If more intense flooding and drought continue to threaten one of its top exports – the state exported $2.3 billion in agricultural products in 2023 – and the federal government continues to cut funding it relies on, what does that mean for the state’s future?

“I think sustainability is an easy argument,” Holt said. “Do you want what we’re doing right now? Do you want to do that in 10 years? If you do, that’s sustainability. Resiliency is (recognizing) we can’t sustain this. We can’t do this forever. We can’t behave like this forever.”

- State fire marshal is investigating troubled Unit 29 at Parchman prison - February 26, 2026

- Mississippi’s Winter Storm Fern losses exceed $107 million, state insurance department says - February 26, 2026

- DNA evidence linked to a Greenville homicide is missing. Now the finger-pointing begins - February 26, 2026