Aallyah Wright, Mississippi Today

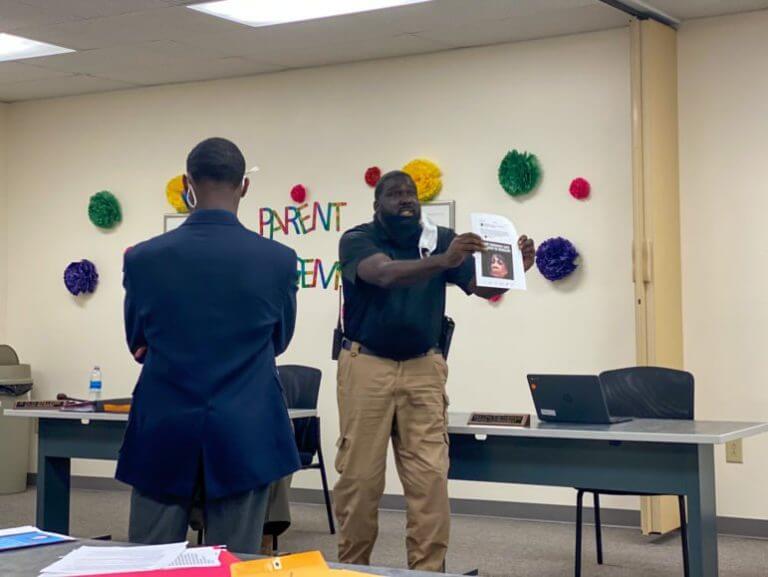

School resource officer Derrell Washington gets emotional as he holds up the picture of Maxine Waters that Fullilove shared on his Facebook.

CLARKSDALE — Nearly an hour into an emotional and intense school board meeting, school resource officer Derrell Washington stood up to address the Board of Trustees of the Clarksdale Municipal School District. As I heard his voice cracking, I looked in his direction, repositioning my foggy glasses on top of my white N95 mask.

With tears in his eyes, Washington said he was offended.

After all, H. Clay “Sandy” Stillions, board president of the Clarksdale schools — a predominately Black school district — held his left hand in front of him to show a piece of paper to the meeting attendees, which included about 10 Black people and three white. It was a photo of a frowning U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters, the Black California congresswoman known for clashing with the Trump administration. The photo bore the caption: “This Is What Coronavirus Looks Like Under A Microscope.”

“Everybody look at this picture and tell me that’s not a scary picture?” Stillions, who is white, said.

Washington immediately replied, “That’s not a scary picture.”

“It looks pretty scary to me,” Stillions responded.

As the country is forced to face a national reckoning on race and racism, this Mississippi Delta school district is, too. That night, a high school senior and youth advocate gathered community members, politicians, and students to protest racism within the Clarksdale Municipal School District.

The Waters photo was a topic of discussion at the meeting because it was shared by a district employee on his personal social media. Rodger Fullilove, director of facilities in the district, shared the meme of Waters on his Facebook page on April 3. Stillions, the board chair, laughed at the post on social media and commented, “Man, that’s some scary stuff.”

When Stillions was confronted about his comments at the board meeting that night, a tense exchange followed that prompted tears from several Black attendees. As it was all happening, my right leg began shaking. I constantly looked down at my audio recorder, trying to collect my thoughts and keep my composure.

Any good journalist is trained to remain neutral while covering meetings like these, but how could I? I looked around the room to connect with all the other Black people present, and all I could think about was, “What if Maxine Waters’ face was replaced with mine?”

And as I’ve personally covered race-related issues several times this year, this moment mirrored the larger issue of inequitable systems and privilege disproportionately affecting Black people.

During this period of heightened racial tensions and lowered tolerance for racism, Mississippi public officials continue to express offensive and racist comments towards Black people. In recent weeks, I’ve written about a white former Clarksdale nurse wishing death on Black protestors and former fire chief calling the Mississippi Legislative Black Caucus a racist symbol.

So there I was again, covering a powerful white leader doubling down on insensitive comments that hurt Black people. This time, he was doing it to our faces. However, I did what so many Black journalists across the country have been forced to do this year: I gathered my composure as best I could in a difficult situation, and I kept observing the exchange.

Aallyah Wright, Mississippi Today

Marchellos Scott, Jr. speaking to press before his protest

At the school board meeting, Clarksdale High School student Marchellos Scott, Jr., 17, stood in front of the district’s central office in his navy blue suit jacket, gray vest and pants, and matching tie. He carried a black briefcase while waiting on his group to show.

Less than thirty minutes before the start of the school board meeting, more than 20 participants held signs in their hands with phrases like “He Must Go!,” in reference to Fullilove, as well as different signs that read “Black Lives Matter,” and “Get In Good Trouble,” inspired by the late civil rights pioneer Rep. John Lewis.

Aallyah Wright, Mississippi Today

Students and Clarksdale Mayor Chuck Espy takes a photo in front of the Clarksdale Municipal School District central office before the protest.

People came to the meeting to ask for the facilities director’s termination, and to chastise the board chair for engaging with his posts.

“(Stillions) said it was funny. He said he liked (the Facebook post) because it was funny,” Washington, the resource officer, nearly yelled in the meeting.

“You pointed (the paper) to us and said “Ain’t this a scary picture.” Washington continued.

“They are saying, this is what the coronavirus looks like, ‘She’s ugly. She’s nasty. She’s disgusting. She’s deadly.’ … I’m a district employee, and I had no intention to come and interrupt the board and say anything because I don’t want to lose my job.”

The photo of Waters was the first of many posts shared by Fullilove, the white facilities director. For example, he wrote “F. BLM. Terrorists” in a June 7 post. The original post has been deleted. Another picture Fullilove shared on his page featured a man holding up a Confederate battle flag with the words, “I wonder if I said, ‘God Bless Dixie!’ How many of y’all will say it back?”

The social media posts sparked outrage among students, parents, and community members on social media. Scott, the youth activist, called attention to it on his own page. Scott and his community group wanted Fullilove terminated immediately.

After multiple community members tagged me in social media posts, I emailed Joe Nelson, Jr., Clarksdale superintendent, Carlos Palmer, school board attorney, and the school board.

In the July 24 email, I attached four screenshots of posts Fullilove made and shared that were hateful and offensive to Black people. I asked the school administration if they were aware of Fullilove’s posts, if they had any comment, and how they determine if an employee speaks for themselves or on behalf of the district on social media. Nelson forwarded my email to the board and Palmer without a response.

In the district’s social media and personnel policies, it states that employees, faculty and staff should never use their personal accounts to speak on behalf of the district and are expected to conduct themselves in positive manners.

This was the center of heated debate at the school board meeting — was Fullilove just using freedom of speech, or hate speech?

“How do we expect children to show up to school everyday … If we don’t take care of them? If we don’t look out for them, then what are we doing?” Bishop Zedric Clayton, newly appointed board member, said at the meeting. “As a parent, I would not want my child pulling into a building where potentially they can run into somebody that sees them as a terrorist. My question is what do we do?”

Originally set to discuss student safety during the executive session, Scott, the 17-year-old passed folders to the district officials, including four of the five board members present (one attended the meeting via phone). This folder had copies of Fullilove’s posts and the district’s policies, among other things.

Scott reviewed his material to the board, reiterating that students don’t feel safe knowing employees spew degrading comments about Black people.

Aallyah Wright, Mississippi Today

Marchellos Scott Jr., youth activist and Clarksdale High School senior, address board president H. Clay Stillions about racism in the district.

“Posts about political affiliations and his values, those are considered freedom of speech, but “F. Black Lives Matter, terrorists, that’s not freedom of speech—,” Scott said.

“No it’s not—,” Stillions, the board chair, interrupted.

“That is hate crime,” Scott said.

“No, it’s not. That is freedom of speech. That is not a hate crime. When you start saying people can’t express their opinion about any group or any church or any organization or any government, you’re controlling speech. That is not hate speech,” Stillions told the high school senior.

“He works at a predominately Black school district.”

“It still doesn’t make any difference. He got a right to express what he thinks.”

“… You indulge in racist comments,” Scott said, referencing the Waters meme.

Stillons, stopped him, “…wait a minute, you’re talking, let me talk. … Yeah, I saw that and I laughed about it. That’s a funny picture, not because she’s Black, but because of her expression.”

“Did you or did you not say it’s some scary stuff under this post?” Scott asked.

“I sure did. You look at that face and tell me that’s not scary,” Stillions responded.

Though multiple people, including board members, spoke up to say Fullilove’s actions on social media were offensive and made them or their children feel unsafe and disrespected in the district, neither the superintendent nor board members took any action regarding Fullilove.

In the end, Stillions thanked Scott for his presentation and said he admired him for speaking up.

In order to move this district, state, and country forward, citizen Ralph Simpson, stated you must “ensure Black lives matter.”

Aallyah Wright, Mississippi Today

Ralph Simpson, community member, tells the board that Black lives do matter.

“When people falsely accuse us, when we can’t walk into neighborhoods where we’re working hard to spend the money to buy houses without getting shot down like dogs, when people put their foot on us ‘til we can’t breath and call our mamas, when we can’t ride in our car without profiling, and then we march in the streets,” Simpson said.

“They’re marching everywhere, Black and white hand in hand …to get the message and understanding to you Sandy Stillions, that Black lives do matter. You can have freedom of speech. But you can’t defringe the rights of others. When you say my life doesn’t matter, you defringe my rights.”

When I started writing this story, I knew I would be criticized for inserting my voice into this. If you go on Facebook and look at the comments on articles I’ve previously written pertaining to racism, you’ll see the critics. But I keep writing and reporting on these stories because it’s important. My job as a journalist is to report the facts, seek the truth, and hold officials accountable.

Part of my job is to speak for marginalized communities who don’t have the space or opportunity to do so and confront racism head-on. In the words of the late Mississippi civil rights activist, suffragist and journalism icon Ida B. Wells: “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them.”

The post As community demands ‘Black lives do matter,’ a reporter views clash between Clarksdale and its school board appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Former Hinds sheriff Marshand Crisler’s bribery conviction stands - March 4, 2026

- National Rifle Association successfully lobbies against bill taking away guns from abusers - March 4, 2026

- Data center proposed for Clinton - March 4, 2026