Eric J. Shelton, Mississippi Today/Report For America

Toni Coleman, Center Hill High School economics teacher, talks her 12th grade economics class as they work on a class project in Olive Branch Tuesday, May 7, 2019.

As Gov. Tate Reeves works to save the School Recognition Program, critics say it ‘intensifies already serious inequality.’

The Legislature created a program in 2014 to reward teachers for student achievement. It was meant to incentivize educators, but many say it’s unfair and inequitable.

By Aallyah Wright | July 29, 2020

CLARKSDALE — Five years ago, New York native Nicole Moore graduated from college in Atlanta, packed her bags and moved to the Mississippi Delta to teach. The Teach For America member was placed at Coahoma Early College High School, formerly an agricultural school deemed low performing.

The new teacher had her work cut out for her at a school where less than a third of students were proficient in reading, according to the Mississippi Department of Education.

Aallyah Wright, Mississippi Today

Nicole Moore, Coahoma Early College High School teacher

Moore and her colleagues made a commitment to improve student achievement at the school, and in a two-year period students saw results. Originally rated a D, the school’s accountability rating climbed to a C — a marked improvement. As a testament to her hard work, two years later, the high school English teacher received a one-time $1,000 reward in 2019.

Moore was one of thousands of teachers to receive money from the School Recognition Program, a merit pay program the state Legislature created in 2014. It rewards schools and educators for student performance. Government officials tout the program as a performance-boosting incentive for all teachers.

Today, the program is at the center of a power struggle between the executive and legislative branch, and it’s the reason why the K-12 budget has not been appropriated this year. Gov. Tate Reeves partially vetoed about $2.2 billion of the appropriation last month because, he said, the budget bill did not fund the program.

“Our schools are improving in many areas. Our education attainment levels are up. And this School Recognition Program is a big reason why!” Reeves wrote in a Facebook post ahead of the veto.

“It is our only performance reward program in the state,” he said. “And it works.”

But critics of the program say it causes confusion and in some cases actually decreases morale for educators. There are also questions about who receives the money and whether the program is racially equitable.

A Mississippi Today analysis shows 53% of the program’s funds have gone to school districts where at least half the student body was white. Of the ten districts receiving the most money from the program, Jackson Public Schools is the only predominantly Black district on the list.

“I have strong objection to policies that use public funds in a way that intensifies already serious inequality,” said Sen. Derrick Simmons, D-Greenville. “The School Recognition Program is one of those policies. From its inception, the program has been inequitable from a racial and socioeconomic standpoint.”

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson, is vice-chair of the Senate education committee and a firm opponent of the program who says “it should be done away with” because it increases inequity in the system.

Eric J. Shelton/Mississippi Today, Report For America

Sen. David Blount, D-Jackson

“The way the money is allocated on a building-by-building basis … there’s little accountability,” Blount said. “I think it’s flawed in its basic concept and it gives a disproportionate amount of money to the wealthier school districts in the state.”

Mississippi Today spoke with educators across the state who said they appreciate the money, but the money alone wasn’t their sole motivating factor to improve student outcomes.

Honey LeBlanc, a veteran teacher in the Long Beach School District who received $1,500 every year, said her friends refer to the awards as “the Delta book money” because it gives already high performing schools in privileged districts money, “when Delta schools need textbooks.”

“I’m very conflicted. Is it enough to recognize what we do day in and out? No. Is it done fairly? No,” she said. “To give money and be recognized is good … but me getting this money? There are other districts that are in need.”

Oxford Middle School teacher Amanda Reiser, who formerly taught in Ocean Springs, said the program is “completely flawed” and doesn’t motivate teachers.

“We’re inspired to keep our students growing and improving,” she said. “Would money be helpful? Absolutely … I feel like it needs to be across the board. Take all of that money and divvy it up to everybody and keep our teacher (shortage) rate low.”

In the Western Line School District, O’Bannon High School teacher Tyjawanda Kirk, a 21-year classroom veteran, received around $1,000 in 2018. Although she believes the program motivated teachers in her district to do more, she understands how it can be unfair to educators whose hard work might not correlate in test results.

“I know in the past I have worked hard to help my students to pass the state tests and achieve goals we set at the time,” she said. “We felt like we weren’t getting recognition or rewards for that. I do think it is a good idea to reward teachers for working and helping students to achieve.”

Research shows merit pay systems have no effect on student outcomes. A 2013 study that examined teacher incentive pay programs in New York, Texas, and Tennessee found most teachers wanted the incentives but felt the programs were unfair. In the survey, 80% of respondents agreed teachers should be rewarded for demonstrating outstanding teaching skills. Ninety percent felt rewarding teachers based on test score gains is problematic. Fifty-five percent agreed the method was fair, whereas 48% didn’t have a clear understanding of the criteria for earning a bonus.

Matthew Springer, co-researcher on the studies and associate professor of education, evaluation, and public policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said there must be a more robust system to evaluate teachers, teams and school performance.

“The metric of an overall school accountability grade is probably not the best system to use, which I am cautious about,” he told Mississippi Today. “The other issue is giving resources to schools is important and we know teachers are the most important determinant in schools for students … I’m really focused on getting high quality teachers in high performing schools.”

In Mississippi, schools and districts receive an A-F letter grade based on several factors like proficiency in math, reading, science, graduation rates and other components. The letter grades are a way to easily convey to parents and the public how each school is performing. The ratings are also used to incentivize teachers and administrators.

Under the School Recognition Program, teachers in A-rated schools or schools that improve from a ‘F’ to ‘D’ or a ‘D’ to ‘C’ receive $100 per student, and ‘B’ rated schools receive $75 per student. Since 2017, the Legislature has funneled about $71 million into the recognition program. In fiscal year 2020, nearly 21,000 certified teachers and staff in more than 500 public schools collectively received $25 million, according to Mississippi Today’s analysis of program records. No administrators can receive an award.

Over the past three years, the program’s intent to incentivize teachers based on accountability ratings has caused problems, including infighting at the district level about how the money is distributed and who is eligible to receive the funds, school officials, lawmakers, and education advocates say.

“When you talk about merit pay, you have to be cognizant there’s so many factors that play into a school and an individual’s teacher success,” said Kelly Riley, executive director of Mississippi Professional Educators. “Whatever we do, we don’t need to do anything that endangers teacher morale, and we’re already having a teacher shortage.”

For the first two years of the program, local districts created a teacher committee to decide how to disseminate the funds and to whom. One of the frustrations, educators say, is that schools don’t see the money until the next year’s accountability ratings come out, which doesn’t promote retention.

Year after year, teachers in Desoto County, Rankin County, Madison County, Harrison County, Lamar County, Jackson Public School, Jackson County, Ocean Springs, and Biloxi schools receive most of the earnings. For the first two years of the program, it is unclear the total number of teachers and staff that received rewards, or how much they received because not all districts submitted that information.

The lack of clarity stems from teacher committees’ decisions on how to parcel out funds the first two years of the program, meaning there’s no specific record of how much money went to an individual teacher or staff member, said Pete Smith, Mississippi Department of Education chief of communications and government relations.

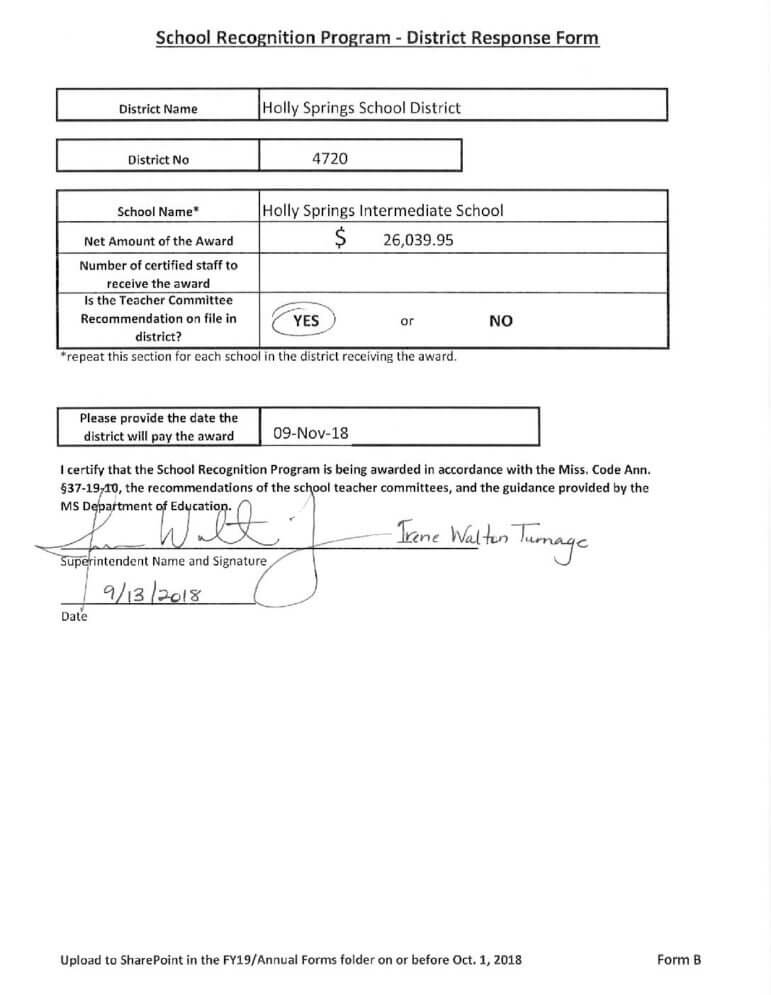

“I don’t think the forms asked how many teachers would receive the money,” Smith said. “It was more or less … we just needed something on record to determine how they were going to disperse that money.”

This is a common complaint from the program’s detractors, who argue the School Recognition Program is problematic.

Erica Jones, president of the Mississippi Association of Educators, said teachers did not have much guidance on how to distribute the money.

Mississippi Association of Educators

Erica Webber-Jones

“They are concerned with how funds have been getting out,” Jones said. “I have a colleague in Hinds County, and they decided to distribute the funds by grade level.”

North Bolivar superintendent Maurice Smith said in his district, two high schools merged to form Northside High School and during consolidation, the principals didn’t submit the district response form in time. As a result, the teachers received the same amount rather than specific amounts to specific teachers, Smith said. This caused frustration among teachers because they didn’t get to make the decision themselves.

Though he felt the program is a good idea, it “needs tweaking,” Smith said.

Lawmakers are aware of the scrutiny around the program.

In past legislative sessions, legislators presented amendments to the bill such as clarifying who can receive the money and allowing superintendents to approve who can receive it, for example. These attempts died in committee.

In 2017, the attorney general’s office issued an opinion stating licensed and non-licensed school district employees could receive the award, meaning all other employees like librarians, counselors, specialists, alternative school teachers, but still no superintendents or principals.

The MDE issued new guidance per the Legislature’s request last year clarifying that the money should only be awarded to current and certified staff of the eligible school and the award must be distributed evenly. In the most recent year, 60% of school districts evenly dispersed the money whereas 36% didn’t. Less than 4% did not submit information. There is also no requirement to pay staff who are no longer employed in the school district.

Former Rep. John Moore, the House education chair who co-authored the 2014 bill, said the program was inspired by a pilot program for performance pay during Gov. Phil Bryant’s tenure. However, this caused “too much competition with teachers” at individual schools, so they wanted to reward schools collectively.

Rogelio V. Solis, AP

Former Rep. John Moore, R-Brandon, in House Chamber in 2015 photo.

Moore called it “a great program,” and those schools who don’t get the money should just “raise their letter grade.”

“If you’re a teacher in a D school and you’re wanting that bonus, then you would be a team leader and encourage teachers in their school… then bonuses could be $2,000 or more, that’s nice Christmas money,” he said. “Some of the teachers actually give some of the money to their (teaching) assistants.”

The future of this program remains uncertain as lawmakers still need to address the education budget, but cannot return to the Capitol yet because of a legislative COVID-19 outbreak.

If the program does survive, teachers feel the program should reward those “who need to see it the most.”

Eric J. Shelton, Mississippi Today/Report For America

Toni Coleman, Center Hill High School economics teacher, gives instructions on her senior class’ final project in Olive Branch Tuesday, May 7, 2019.

“Those teachers that did not get money … I don’t even know them but I can vouch that they’re doing the absolutely best with what they have, and they are being punished,” Toni Coleman, a Center Hill High teacher said. “When they are continually getting chastised from funds and pay raises and any sort of recognition other than bad recognition, what’s left?”

READ NEXT: Aallyah Wright: How I reported the School Recognition Program story

The post As Gov. Tate Reeves works to save School Recognition Program, critics say it ‘intensifies already serious inequality.’ appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Legislature, flush with cash, passes budget, completing work for 2024 session - May 3, 2024

- Marshall Ramsey: Sick Burn - May 3, 2024

- On this day in 1850 - May 3, 2024