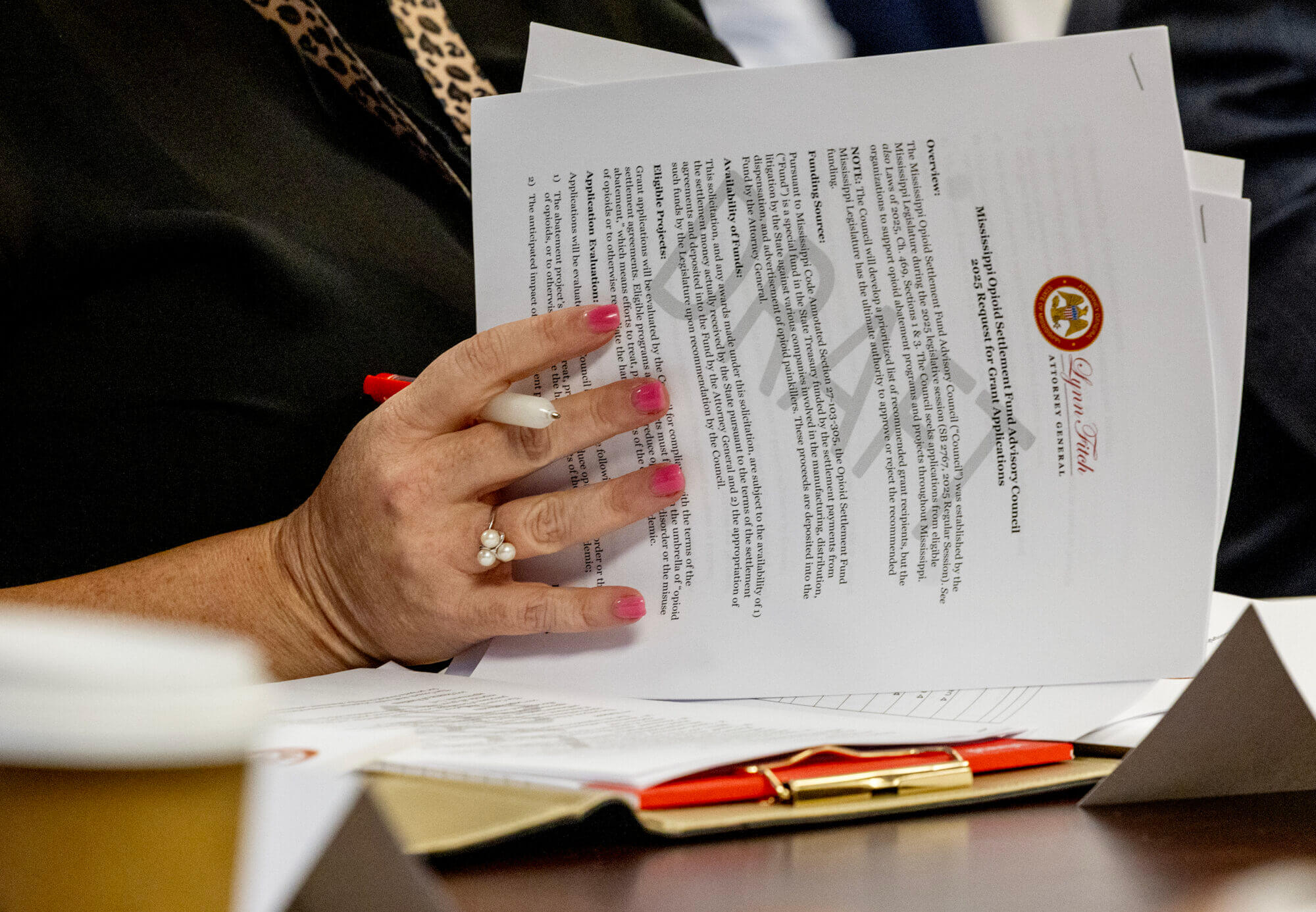

Teresa Buck steadies her hand as she aims a screwdriver toward the frame of what’s to become a bedroom wall.

In north Jackson’s Broadmoor neighborhood early Saturday morning, Buck and more than a dozen volunteers, mostly women, drilled away at fresh lumber, laid glue and lifted frames, following the blueprints for Buck’s future home.

Hopefully by the new year, she will be crossing the threshold of her new house built by Habitat for Humanity, something the 32-year-old has been waiting for since she first applied last fall.

“ I’m getting nervous because I’m fixing to be on my own,” Buck said. “I’ve never been on my own.”

Buck isn’t new to the Habitat for Humanity model for homeownership. Her mother purchased her first home from Habitat for Humanity in 1999, and they’ve been living in Jackson’s Midtown neighborhood nearly her entire life. She said that by buying a home on her own, she’s taking a leap of independence. Buck has three children and wants to set an example.

“ I want to learn how to be responsible so I can show my kids how to learn to be responsible and not to depend on somebody else,” she said.

Choosing to build in Jackson wasn’t a hard decision for her, she said. She wants to remain close to her mother and keep her children at the same schools.

“This is my home. I know the crime and stuff is bad, but this still is my home,” Buck said. “I love Jackson. I was born and raised here, and I don’t want to leave Jackson.”

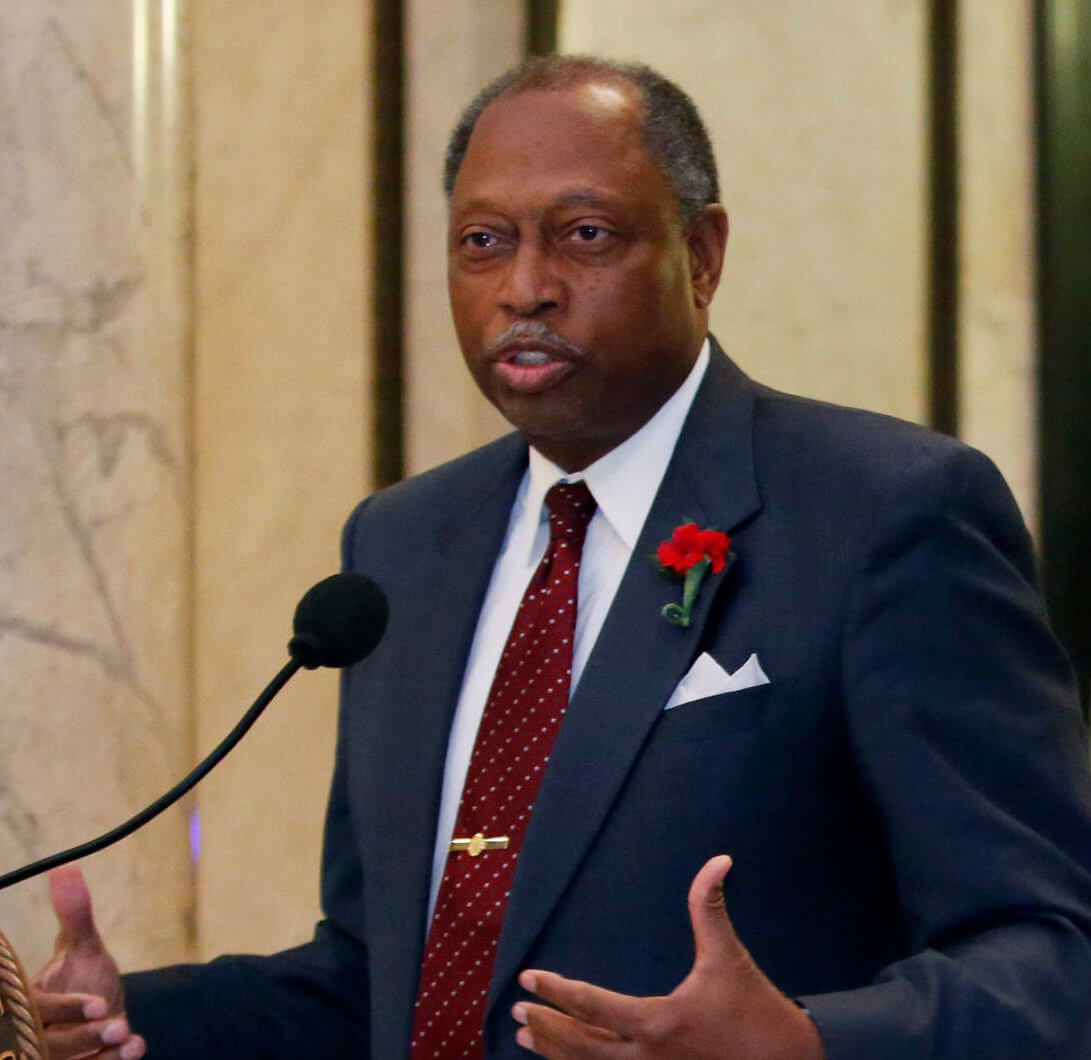

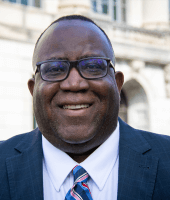

Merrill McKewen, CEO of Habitat for Humanity Mississippi Capital Area, said that one of the missions of the nonprofit organization is to improve the living conditions for families and create successful homeowners. Habitat operates in the Hinds, Madison and Rankin counties, and since its formation nearly 40 years ago, it has built more than 660 homes.

“Every morning at least 2,500 people wake up in a safe, decent, affordable house because of Habitat,” McKewen said.

This work means transforming blighted properties and empty lots and offering 30-year, zero interest mortgages on them. McKewen stresses that Habitat for Humanity is an economic engine and doesn’t give homes away for free. Homeowners spend up to 80 hours working on their home and at least 125 “sweat equity” hours volunteering.

“It’s a passion to help my brothers and sisters in Christ get a chance to fulfill a dream. It’s something that they qualified for, worked for, and that they take the responsibility for. That’s why it’s a hand up, not a handout,” McKewen said.

She said it’s rare that a homeowner faces foreclosure and has to move, but it happens.

“My saddest day on the job is when I have to go stand in court in front of a judge to have them evicted, or sometimes they just abandon the house,” she said. “As tragic as that is, we then take the house, refresh it, bring it up to the standards of which we’re building now, and sell it to another qualified Habitat homeowner.”

In recent years, Habitat for Humanity has built 28 houses in the Broadmoor neighborhood where Buck will live, and McKewen said the work will continue. Placing Habitat builds in the community encourages neighbors to invest into their own homes. She hopes that impact can be felt for generations to come.

“I would like to buy 15 blighted properties or receive them if people bless us. If we could get 15 properties in the Broadmoor area, we could probably get close to the commitment I made pre-COVID, which was to impact 100 houses in the area,” McKewen said.

In building her first house, Buck said she hopes to impart a legacy for her children. She wants them to grow and thrive in the city that she loves, all while living in a safe neighborhood. She already imagines herself on her porch or watching her children play at the nearby park.

“This will be my property in 30 years that I can call my home,” Buck said. “This is going to be mine, and I could leave it for my kids if they want it.”