Editor’s note: Mississippi Today Ideas is publishing guest essays from people impacted by Hurricane Katrina during the week of the 20th anniversary of the storm that hit the Mississippi Gulf Coast on Aug. 29, 2005.

As I flew home from a three-week economic development trip to Japan on Aug. 24th, 2005, I became aware that a tropical storm was in the Atlantic headed toward Florida. That day it was named Hurricane Katrina by the National Hurricane Center.

It hit southeastern Florida as a Category 1 hurricane on the 25th and then traveled into the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico that evening.

After Hurricane Camille hit Mississippi’s Gulf Coast in 1969, the state had conducted annual drills and practice sessions in preparation for the next major hurricane. Based on those preparations and practices, the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency (MEMA), the Mississippi National Guard and the Mississippi Highway Patrol joined with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the Mississippi Department of Transportation (MDOT) along with county and city responders and private companies in preparing for a serious hurricane.

As Katrina approached, we established a unified command structure that tied the various governmental structures together, which strengthened our operations. This was especially important since the state had more than 3,000 National Guard forces on the ground in Iraq. Private companies such as public utilities, airports, ports and shipyards tied into the command structure.

By Aug. 27th Katrina had begun to change course, turning north and gaining strength. Dr. Max Mayfield, head of the National Hurricane Center, called me that evening and told me the hurricane would probably come ashore in Mississippi and would be worse than Camille.

I asked him to get the government and the news media to start saying that because our evacuation efforts were too small. He agreed and once the media started saying this hurricane would be worse than Camille, our evacuation became much larger. Our citizens knew how terrible Camille had been.

The eye of the storm came ashore early the morning of Monday, Aug. 29th, where Mississippi and Louisiana come together at the mouth of the Pearl River, with the strongest part of the storm, the right front quadrant, covering the entire Mississippi Coast and more. The wind speed, which had been a Category 5 storm until Sunday, was knocked back to a high Category 3 when the eye passed over the mouth of the Mississippi River and the Chandeleur Islands.

While the winds were down to 125 mph, the storm surge was enormous. The storm surge in Hancock County was 30 feet plus the waves on top. At Waveland that equaled 37 feet!

Afterward at Waveland there were no habitable structures remaining. Seventy miles to the east at Pascagoula the storm surge equaled more than 20 feet on Beach Boulevard.

As it went forward, Katrina threw off 11 tornadoes in southeast Mississippi, including population centers like Laurel and Meridian. Thirty more tornadoes were spread across other Southeastern states.

No airplanes were allowed to fly in the hurricane’s path, but my office made an agreement with USDOT to allow the governor’s office to fly the state plane to Gulfport-Biloxi airport, provided the Mississippi National Guard cleared one runway by Tuesday morning.

After I landed, we had a quick leadership meeting; then I saw my wife Marsha, who had gone down Sunday to Camp Shelby to thank the large elements of the Mississippi National Guard and Highway Patrol who had sheltered there.

She traveled to Gulfport when the convoy was able to clear one lane of U.S. Highway 49 on Monday. It was a seven-hour trek to cover what was normally less than a two-hour drive.

After the meeting, the Guard bought up three helicopters for damage assessment. I asked Marsha to go, but she said she had done it earlier that morning and didn’t want to see it again. My team took up two of the choppers, and I let the news media take the third.

The devastation was shocking. There was utter obliteration. As far as the eye could see, it looked like the hand of God had swept away the whole Gulf Coast.

We flew first over Gulfport and then went all the way to the Pearl River. Gulfport had 10 to 15 feet of water flow through it, and much was washed away. As we went farther west, most everything seemed to be covered with several feet of debris and residential neighborhoods were flattened.

A new verb was created: “slabbed,” as in my house was “slabbed,” meaning there was nothing left but the slab. Many thousands of houses and other buildings were “slabbed” in never-before-seen destruction.

And it wasn’t just residential destruction that littered the Coast. Major industrial sites were badly damaged. As I flew over Pascagoula in the helicopter, I saw that Huntington-Ingalls Shipyard was covered in debris, and Chevron’s largest refinery in the United States was also covered with debris.

It was estimated that Katrina reduced US energy output by 20%, including offshore.

Remarkably, all the damage and debris were not on the beach. Many tons of debris were piled up on the railroad right of way; more were miles past the right of way. In very few places could you even see the grass as it all was inundated under trees, cans, waste from buildings, etc. It was scary.

When we landed at Gulfport at the end of the ride, Bert Case, a leading Jackson television reporter, asked me, “Governor, after seeing what you saw on the helicopter ride, what is your worst fear?” I told Bert my biggest concern was how many bodies will we find under all that debris.

By God’s grace, the number of fatalities we had was 238 – too many for me, but fewer than expected. And one-third of those were not in the coastal counties. We had a small fraction of the number of fatalities compared to Louisiana, which numbered 1,600 to 1,800, despite the fact that Mississippi bore the brunt of the storm.

While the death toll turned out to be far fewer than feared, the devastation to property and the terrain was beyond anyone’s expectation. And it was not only a coastal calamity. The hurricane force winds extended to north of Columbus in north Mississippi. As I mentioned earlier, a third of fatalities from Katrina were not on the Coast but north of there.

As we united to rescue survivors and to stay conscious of security and looting (we had very little looting), we laid out our priorities. On Wednesday – two days after the storm – I shared those priorities with senior staff of the governor’s office.

I laid out the literal goals of our work: return heavy employment to the Coast as very few people would return unless there were lots of good jobs; rebuild or replace the tens of thousands of homes, apartments or condos because people would not return unless there was ample, good quality housing; and a quick opening of high quality schools for their children’s education.These priorities were pursued from the first week after the storm.

A main method of achieving these goals was the work of the Barksdale Commission for Recovery, Rebuilding and Renewal, chaired by Jim Barksdale of Jackson. The 50-member commission was made up of leaders from around the southern half of the state and as far north as Greenwood. The makeup reflected the fact that Katrina was not just a coastal calamity.

The commission was very active, and a highlight of their work was a “Charrette,” a French word for “cart,” which in this version had morphed into a meeting of a hundred or more professional architects, engineers and other gifted designers who proposed and assessed multiple ways to rebuild and reestablish the Coast area in smart, more livable fashion.

To achieve our goals, we had to clear the debris from all the areas it covered. We removed 47 million cubic yards of debris at a cost of $717 million. More than 57,000 homes, condos or apartments were rebuilt or replaced in the first five years.

From the Charrette, ideas were born like the Mississippi Cottage, an improvement over the “FEMA trailer” which was the federal standard but was greatly inferior to the Mississippi Cottage. We were able to provide more than 3,000 families with far superior Mississippi Cottages.

Just before the Charrette began, the Legislature had finished a special session focused on Katrina and gaming.

Gaming was legal in Mississippi in counties that touch the Gulf of Mexico or the Mississippi River, if citizens chose to have it by referendum. Two coastal counties (Harrison and Hancock) had voted to have casinos in the early ’90s when the state legislation was passed.

Gaming on the Gulf Coast had become a major industry, employing more than 30,000 citizens directly or indirectly. Before Katrina it generated 6% to 9% of state general fund revenue.

Because of the requirements of the 1990s’ legislation that legalized casinos on the Coast, the casino gaming floor had to float on the Gulf of Mexico. During Katrina every casino gaming floor but one broke away and floated on shore, some by hundreds of feet. The Beau Rivage gaming floors uniquely floated by being strapped down so they could not float away.

A major issue in the special session was whether to allow the casino floors to be built resting on land. Many casino companies insisted they would not rebuild if the casino floor had to float.

Quite a number of legislators, including House Speaker Billy McCoy, opposed gaming as did most of their constituents.

Even though Coast leaders and their constituents believed the Coast would be decades rebuilding without the casinos, attracting tourists and creating jobs and revenue, allowing the on-shore change was not a sure thing.

The Senate leadership, all Republicans, did not want to go first in passing the onshore casino law. So, I had to ask Speaker McCoy to allow it to come to the House floor and pass. He realized he should put the Coast and the state’s interests first. He did so, and the bill passed 61-53, with McCoy voting “no.”

I will always admire Speaker McCoy, often my nemesis, for his integrity in putting the state first.

Many legislators stepped up strongly, not only during the special session, but through the Katrina ordeal: such as Bobby Moak, Tommy Robertson and Billy Hewes.

The Legislature could hardly have been better during Katrina. Legislators did not try to take charge. They realized the process and structure we followed was working.

A lot of state legislatures didn’t have that discipline; but led by Lt. Gov. Amy Tuck and Speaker McCoy, ours did.

State employees, from first responders, National Guard, Highway Patrol to social workers, secretaries and others were magnificent in adjusting to the remade environment.

My staff was sensational. After Aug.29th everything changed. But they adjusted overnight! They made tough decisions, while taking over new responsibilities. People like Charlie Williams, Paul Hurst, Jim Perry, Marie Sanderson and many others not only led but oversaw senior staff.

The local officials and their employees were strong and smart from the beginning, making the united command structure work extremely well.

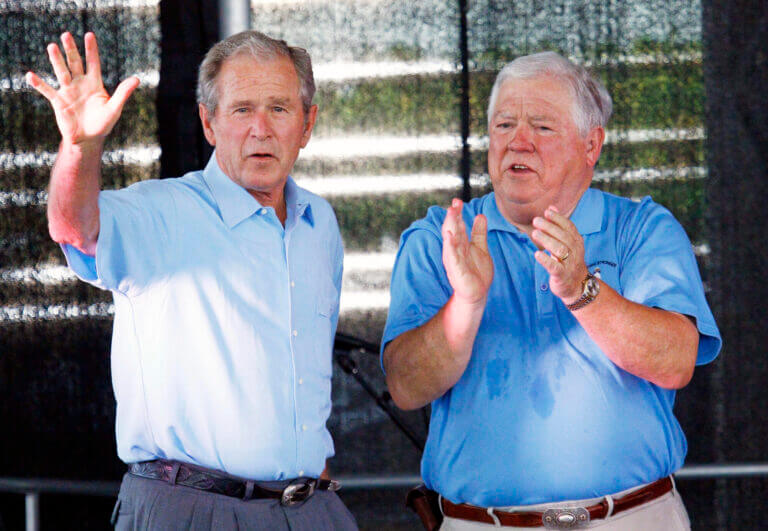

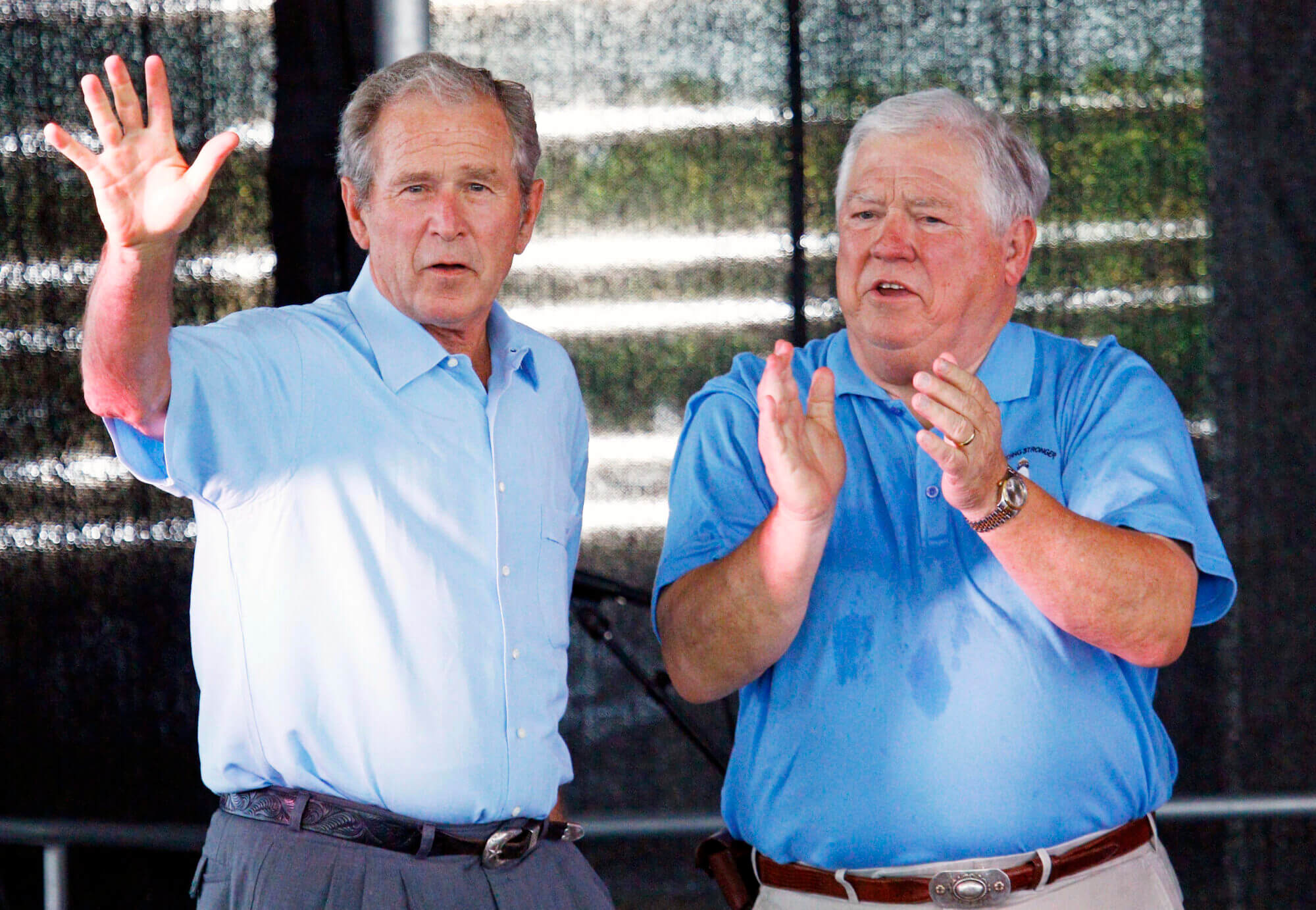

Attached to the unified command structure were federal partners.The Bush Administration got criticized early after the storm, but the federal government did a whole lot more right than wrong. President Bush not only visited many times to check on progress, but he and his administration also favored the states and citizens on every discussion. He bent over backwards to help us, and so did the Congress.

Mississippi Sen. Thad Cochran, as chair of the Appropriation Committee of the Senate, was the biggest star for us, but fellow Mississippi Sen. Trent Lott got many crucial decisions made in our favor. Our members of Congress, both Democrat as well as Republicans, worked tirelessly for us.

And we had support from right and left in Congress, such as Democratic Massachusetts Congressman Barney Frank. Similarly, 46 of our sister states sent people or resources to help.

The American people proved again that they are the most generous in the world, and not just with money. Yes, the federal government supplied Mississippi and our companies and citizens with $25.5 billion. Tens of millions more came from companies, industries, private citizens and charities.

People gave something more valuable than money, something irreplaceable: their time. More than 960,000 people volunteered to help with the recovery; 600,000 in the first year and 360,000 in the next four years. These are the numbers of people who registered to help, work, rebuild, all of whom registered with churches, charities and organizations.

Finally, the greatest hero of Katrina, the people of Mississippi who got knocked down flat, got back up, hitched up their britches and went to work. They went to work helping themselves and helping their neighbors. Our people did more in Katrina to improve our state’s image than anything that has happened in my lifetime.

I close by saluting my wife Marsha, who spent 70 out of the first 90 days after the storm on the Coast, helping people who didn’t know how to get help. Marsha was the face that showed the state cared and was doing all it could.

Haley Barbour served as Mississippi governor from 2004 to 2012. From 1993 to 1997, he served as chairman of the Republican National Committee, In 2015, he wrote “America’s Great Storm: Leading Through Hurricane Katrina.” A native of Yazoo City, Barbour still resides in his hometown with his wife, Marsha. They have two sons and seven grandchildren.

Editor’s note: Marsha and Haley Barbour donated to Mississippi Today in 2016. Donors do not in any way influence our newsroom’s editorial decisions. For more on that policy or to view a list of our donors, click here.