Anna Wolfe

In a brief moment of concentration, Zen’Daiya examines her laptop before she returns to dancing throughout the classroom at the Boys and Girls Club Capitol Street unit on Sept. 21, 2020.

Mississippi is getting devices to every child. That’s just the first step.

For the first time in state history, every student in the state will have their own device, though hurdles remain in access to internet and connectivity.

By Kate Royals | Oct. 1, 2020

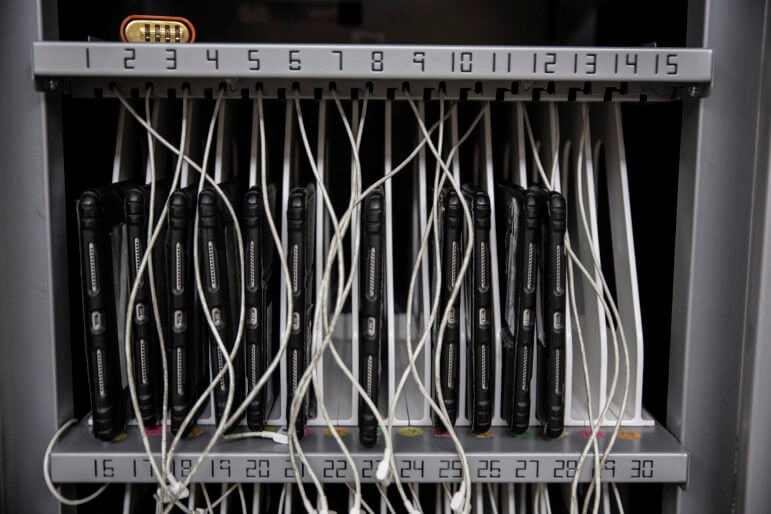

Nearly 400,000 MacBooks, Chromebooks, iPads and other devices are en route to students and teachers across Mississippi – a massive undertaking prompted by the state Legislature and implemented by the Mississippi Department of Education.

But in rural school districts where a rainstorm can disrupt internet connection, or students don’t have connectivity even on a sunny day, a device is only the first of many hurdles.

State Superintendent of Education Carey Wright says ensuring students have adequate internet access and educators have the training they need will be a challenge, but the state has proven it can do extraordinary things in a crunch. They did so when they secured devices for all students and teachers in Mississippi – at the same time technology for distance learning was in high demand globally because of the pandemic.

In July, the Mississippi Legislature allocated $200 million to help schools implement virtual learning both during and after the pandemic. In all, $150 million will go toward helping schools purchase technology and devices, while the remaining $50 million focuses on expanding broadband access in areas with little or none.

“I’ve talked to people around the nation, and there’s not anyone doing something as detailed, as thorough, as coherent as what Mississippi is doing,” said Wright in an interview with Mississippi Today.

Brent Engelman, director of education data and information systems at the Council of Chief State School Officers, a national organization comprised of the heads of state education departments, echoed Wright.

“Mississippi is among the states leading in the important equity work of closing the digital divide and ensuring students and teachers have what they need for digital learning,” said Engelman. “Importantly, Mississippi has focused not just on devices and wireless access but also funding the curriculum and professional development needed to support this use of technology.”

While it’s important that students have the devices they need, the more immediate mammoth challenge is making sure children have access to internet in an extremely rural and under-connected state.

And as many students and teachers wait on devices, the first semester of the school year is nearly halfway over. The divide between those with access to updated technology and those without has never been more apparent.

In Yazoo County School District, there were enough devices on hand for all of its 1,384 students to share a couple weeks into the school year – a best-case scenario for a school district that was not “one-to-one,” meaning every student has a device. They placed an order for updated devices under the Equity in Distance Learning Act and, like most other districts, are still waiting on their delivery as of late September.

While they’re waiting, the district is using the equipment it has, some of which is outdated. There was a lag for some teachers and students who had to familiarize themselves with the new learning management system and applications, in addition to the devices themselves.

Andrea Edgecombe is an interventionist for elementary schoolers at Bentonia Gibbs Elementary School in Yazoo County. After teaching for six years, she now works with small groups of students who are struggling academically.

This year, she has 14 virtual learners and 19 traditional students. The Yazoo County School District is implementing a hybrid model of school this year with the option for all-virtual learning.

While there have been positives in her experience with distance learning – like making her own schedule so she can focus solely on the virtual learners during her morning hours, and the fact she and her students have access to devices – there are still challenges.

“There are lots of internet issues (on the part of the students), and lots of struggles with the younger kids and the schedule,” she said. “They have a scheduled time to hop on Zoom with me every day, and I roughly have anywhere from five to 10 no shows a day depending on the day.”

The issues include students being kicked off Zoom, excessive delays, and for some students who live in rural areas, a loss of internet when it rains.

Edgecombe, who also acts as the technology liaison at her school, said that while she’s glad there have been new applications to try and accompanying professional development, there has not been any training on the devices themselves.

“There are some teachers who are not as familiar with not only our laptops but also the students’ Chromebooks, so it’s made it difficult for those teachers to answer questions from parents,” she said. “In that same sense, it would’ve been great if we could have launched some sort of virtual town hall for parents to train them (as well).”

While Edgecombe is glad everyone will be receiving new devices with funds from the Equity in Distance Learning Act, there is a concern that when they do receive the new devices, there will be yet another learning curve to overcome.

“What’s a little bit scary is when they do come out with these computers, what if they come in and they’re different than what parents and kids are used to? Then we’re going to have to re-teach everything,” she said. “I’m hoping all our apps and programs work the same way on these new devices.”

In nearby Holmes County Consolidated School District, the district is operating entirely virtually. All students received devices in August after the district placed an order using other Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act funds, and teachers had just been given new laptops the prior school year.

The district has done what it can to improve access for students – including putting hot spots in school buses and apartment complexes around the county for WiFi access at the beginning of the pandemic – but hurdles remain.

From weather-induced internet outages, attendance issues to some students’ and caretakers’ unfamiliarity with technology, Holmes County Central High School teachers Kristie Montgomery and Ravi Dutt both agree the virtual learning experience has been a challenge.

They’ve seen students logging on to class from cars or on front porches with borrowed WiFi.

Luckily, they said, students who miss virtual class usually show back up a day or two after the teacher calls the parent to let him or her know.

“I had a student who logged in to class while sitting in the backseat of a car. I asked why she was sitting in a car and she said, ‘Mr. Dutt, there’s nobody at home and my mom doesn’t want me to be at home by myself,’” Dutt said.

So they worked out a system: The mother parks her car underneath a tree, goes in to work and the student logs in to class from the backseat.

“It was very touching to me to know how hard she’s working to log in to her class,” said Dutt.

But Montgomery, who has around 100 students herself and another nearly 100 students of a colleague on maternity leave, said despite hiccups at the beginning of the semester, she finds she’s getting into a good groove.

“In the beginning it was a little bit overwhelming … but it’s almost like a ritual now,” she said.

Wright, the state superintendent, and other state officials say as the devices come in, the focus will shift to other areas that will help educators effectively implement distance learning.

Wright argues the combined focus on curriculum, professional development and expanding access to connectivity is the key not only to students keeping up during the COVID-19 pandemic but also to improving inequities that existed before the pandemic.

Since the state Legislature appropriated $150 million in federal coronavirus relief funds toward the effort in July, administrators at the Mississippi Department of Education began an effort that could normally take one year or more and completed it in six weeks.

In those six weeks, the department conducted needs assessments from every school district, developed minimum specifications for all of the technology, conducted countless webinars with school superintendents and technology directors and finally ordered a massive number of devices from CDWG, a technology solutions provider company headquartered in Illinois.

Eric J. Shelton/Mississippi Today, Report For America

iPads are prepared to be handed our to parents for their children at Eastside Elementary Monday, March 23, 2020.

School districts were able to choose between three types of devices: Windows laptops, Google Chromebooks or Apple MacBooks or iPads.

The devices are the first step in the roll-out of the Equity in Distance Learning Act, which also includes components around professional development for teachers and curriculum.

J.C. Lawton, director of information systems at Columbus Municipal School District, said his district is using the funds to provide devices to students in pre-kindergarten through eighth grade. All high schoolers already had individual devices.

Lawton said despite some hiccups – such as not being able to thoroughly research the type of device before being locked into the program – the experience of purchasing the devices has been a good one.

“I’m excited to be able to put 2,700 devices in students’ hands,” said Lawton.

The Equity in Distance Learning Act gave a deadline that all devices must be delivered to school districts by Nov. 20, or school districts would not be reimbursed for their orders. The clock was – and still is – ticking, but officials at the state education department say the devices are on track to meet the deadline.

“During a global drought on Chromebooks, we have 90% of our (Mississippi’s) order on the ground in the United States right now,” said John Kraman, chief information officer of the Mississippi Department of Education, told the State Board of Education at a meeting last week. “There’s more work to do on the Windows, Macs and iPads.”

Wright is confident there won’t be any issues meeting the delivery deadline. She said this is in part because Mississippi used bulk purchasing power – that is, ordering all school districts’ devices in a uniform manner instead of individual school districts ordering their own products separate from one another.

“We’ve seen across the nation supply chains breaking down, and they (CDWG) have been on top of it in Mississippi,” said Wright in the interview with Mississippi Today. “That’s been a big plus for us because of the quantity (of the order). If we had just pushed the money out to districts, each little district would have been its own entity standing in line. I’m glad we did it the way we did it.”

But some school districts still went out on their own. Ken Barron, superintendent of Yazoo County School District, is one of those.

“We weren’t going to sit around and wait” for the Legislature or for MDE, said Barron. Forty percent of students in his school district chose the virtual option. “I was concerned about having the devices in students’ hands in time.”

Barron said his district conducted a reverse auction which resulted in such a good price he decided to replace the entire fleet of devices in the district. As of late September, they were on schedule to be delivered in October, said Barron.

Stacey Graves, the chief financial officer of DeSoto County School District, said her district participated in the state’s program, officially called Mississippi Connects, and the process worked well for them.

“What we’re getting, you just can’t beat it,” she said. “I’m getting 27,770 devices for a little over $3.8 million,” or an average of $137 per device.

Graves also appreciated the specifications of the devices, including cases and insurance.

“These come with everything you could ever want on them, including special insurance for if a kid drops it,” she said. “In the first two weeks of our distance learning, we’d already had four kids drop their devices.”

Graves admitted, however, that figuring out how to identify why particular students don’t have access is difficult.

“We surveyed all of our students during registration, so we know who does not have internet connectivity, but we don’t know why they don’t have it,” said Graves, whose district had nearly 35,000 students last year. “We are working on gathering that information to determine the best solution to connectivity for each student.”

Phillip Burchfield, executive director of the Mississippi Association of School Superintendents, oversaw the Clinton Public School District as it transitioned to a “one to one,” or one device for every student, school district in 2012.

He said superintendents have concerns about the longevity of the devices.

“It takes time for teachers to understand virtual learning (and devices), and that’s not even mentioning the kids,” said Burchfield. “So by the time we were making strides (on that front), our hardware, our computers, are going to be on their last leg. A big concern of superintendents is where is that money going to come from? Is that going to be left up to individual school districts who are already on a tight budget?”

Money from the state education department covered 80% of the costs of devices, and districts were expected to match 20%. The Legislature encouraged schools to use funds from another pot of federal funds to cover the 20% – but some districts were faced with more costs.

Columbus Municipal, for example, is one. That school district ended up having to pay an additional $467,738 from its reserves to cover its order – not an insignificant cost for a district of just under 3,500.

Districts and the state education department are working ahead as devices purchased through the program begin arriving. On Wednesday, West Point School District became the first to receive its order. Tate County School District is scheduled to receive its Friday.

“Now we need to pivot to ensure children are learning with these new devices,” said Wright, noting the department has already created a large team to coordinate statewide professional development for teachers.

She also said the department and school districts are doing what they can to improve internet access by working with providers and purchasing hot spots and data plans.

Wright and other educators have echoed a common theme throughout the pandemic: inequity in education is a major issue during normal times, but the presence of COVID-19 has highlighted it to an extraordinary degree.

“When COVID hit, the whole equity issue was just front and center,” said Wright. “You either have internet or you don’t. You either have a device or you don’t. It shouldn’t be a privilege.”

The post Mississippi is getting devices to every child. That’s just the first step. appeared first on Mississippi Today.