“There are a lot of things happening in our country that students have feelings about.”

As schools reopen during a pandemic, post George Floyd, teachers have more to prepare for than just educating their students. Are they getting the training they need?

By Aallyah Wright and Kelsey Davis Betz | Aug. 17, 2020

After 23 years of teaching, Zimiko Turner has developed a rhythm for back to school preparations. Usually, the summer is about stocking up on supplies and deciding how to decorate her classroom.

This year, she’s buying extra face masks for her students, making sure she has enough hand sanitizer, and brainstorming with colleagues about how to care for children without risking infection.

“This particular time of the summer is spent (asking) …What theme are we going to use this year?” said Turner, a high school chemistry teacher at Columbus Municipal School District. “And now we’re wondering, ‘Are we going to be able to go back safely? How is this going to affect my health? What kind of danger am I putting myself in?’”

Like most teachers, she’s expected to have answers for students and be prepared when they return. But what has been nearly impossible to prepare for is the stress, grief and trauma her students will be bringing with them when they come back this year.

Some teachers are taking advantage of professional development to help prepare them for this. One afternoon in early July, 29-year educator, researcher and consultant Joe Olmi welcomed teachers via Zoom to a three day virtual training on how to approach the reopening of schools. This training, hosted by the Mississippi Professional Educators and The Impact Education Group, was different than most.

Rather than focus solely on safely reopening schools, the training centered around how to address social, emotional and mental health challenges students and staff may bring with them into the classroom this fall. The controversy over the former Mississippi state flag, a deadly pandemic, the upcoming general election and the Black Lives Matter Movement, for example, are all potential issues impacting students, Olmi told the group of more than 20 educators.

“For us in the state of Mississippi, it encompasses far more than COVID-19. And if we fail to think about these other societal issues then we’re going to be at a significant disadvantage when our kids show up in mid-August,” he said.

Teachers shared their questions and concerns with Olmi: What about tracking my students who may have moved out of the state? Or students who moved into the state who have to adjust to a new environment? As an educator, how do you meet the emotional needs of children with special needs if they choose to be a distance learning participant? What about students who deal with deaths related to COVID-19?

Teachers say they are more or less expected to have answers to these questions without having had the training to help them.

Every school district had to submit their reopening plans to the Mississippi Department of Education by July 31. They had three broad options to choose from: going back to school “traditionally” (face-to-face), resuming classes completely online, or creating a hybrid version that incorporates both.

What’s not required in those plans is the steps that school district leadership must take to help teachers advance their understanding of social emotional learning (SEL) or how they’ll provide training on creating a trauma informed classroom.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines SEL as a process for which youth and adults apply knowledge and skills to “understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

CASEL advocates for social emotional learning in prekindergarten through high school and provides “high quality, evidence-based” resources around SEL for educators and policy leaders, according to its website.

This type of training is important because it helps identify students’ mental health needs earlier in their academic career and helps the students equip them to make better decisions, Olmi, the researcher, said. It also teaches kids to think critically about their place and purpose in society. In Mississippi, there is no legislation in place that deals with training teachers how to educate traumatized kids.

“As far as my district, we have not had that training. We haven’t had the opportunity there to explore those areas and what we can do as educators to meet the needs of those students,” Turner said.

She isn’t alone. There currently aren’t state-mandated educational standards that measure how well school districts meet their students’ social and emotional needs. With the onslaught of grief that COVID-19 has ushered in, the need for this type of training is necessary, education advocates say.

Research shows adults and kids already grapple with the meaning of their own race and ethnicity and how it relates to their role in society. This wrestling with mental health and trauma needs has been exacerbated by the impact of the pandemic and heightened levels of police brutality and vigilante killings.

“With some of the events that have occurred over the summer, for example the George Floyd incident, some of our students may come back to school fearful of different things — of being discriminated against or things that they’ve heard or things that they might have viewed on television,” said Erica Jones, president of the Mississippi Association of Educators.

That’s why, Olmi says, it’s imperative for educators to know how to navigate these challenges with students before the problem escalates.

“It’s almost too late or the prognosis is certainly much more negative if we’ve given them all these years to solidify these behaviors that are unhealthy or these behaviors that don’t fit with society,” he said. “Do we wish to be the guard rail around the curve or do we wish to be the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff?”

In order to effectively address these complexities, Olmi says teachers must acknowledge their own prejudice, implicit and confirmation biases, which is critical as students come back to school.

He added it’s important for educators to note the implications of their own biases and its susceptibility on students. The University of Southern Mississippi’s School Psychology Program, where Olmi is a professor, created a resource manual for teachers, administrators, parents and students.

In addition to this resource, he emphasized the need for schools to produce a social emotional plan for re-entry. Some of the items recommendations include planning ahead to address the needs of staff to prevent burnout, prioritizing a fully staffed mental health team with positions like counselors, school psychologists and social workers, among other suggestions.

“What are they going to do when that kid walks in and says, ‘I’m not putting on a mask’?” Olmi said. “There’s all kinds of negative opportunities that concern me and schools have to be prepared for the worst case scenario not the best case scenario.”

Some districts are being proactive about how to construct these plans.

For example, at Columbia High School, 22-year educator Shelley Putnam mentioned her district is creating space to have discussions around inequities and injustices, critical consciousness, developing character lessons, and social emotional learning.

“We recognize there are a lot of things happening in our country that students have feelings about,” she added.

Alison Rausch, a special education teacher in Prentiss County Schools, said her main focus is to meet her students’ basic needs when school reopens. In the past, schools focused a lot of time into “passing a test,” and now it’s time to just be there for students, she said.

“I want to make sure your social emotional needs are met. I want to make sure you have the food that you need. I want to make sure that when you’re ready for academic learning, we do that,” Rausch said. “As we begin the process of opening schools I think if we focus on the child instead of everything else around them, I believe those needs will be met.”

As a way to provide resources for teaching holistically, the Mississippi Professional Educators holds regional trainings around the state each year. And now with the uncertainty of what learning looks like, it’s important to provide professional growth for members, Kelly Riley, executive director, said in an email.

“This pandemic and the subsequent school closures last spring have been very stressful for students, teachers, and parents,” she said. “I am confident these trainings and other resources have proven beneficial to our members’ planning for the upcoming school year so that they may effectively support and teach their students during this traumatic event.”

While there is currently no statewide structure in place that ensures SEL training for teachers, it has been on the minds of state educational leaders.

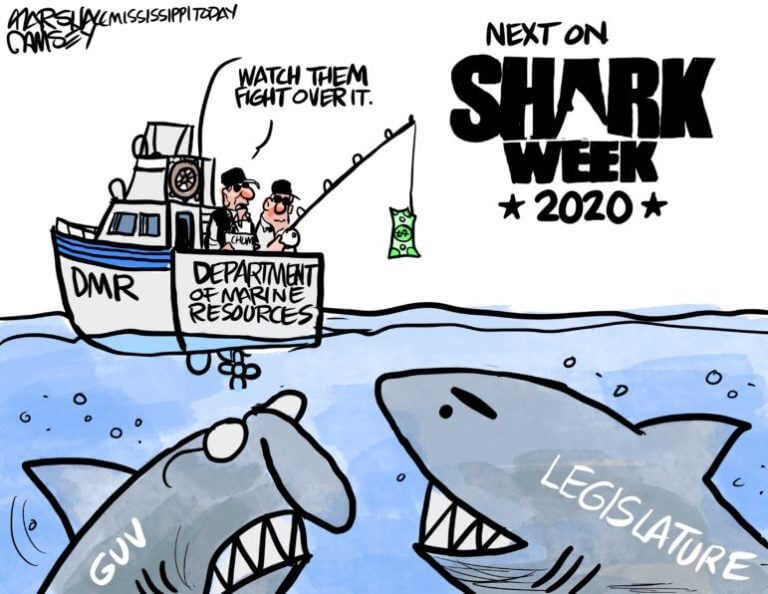

Before COVID-19 derailed the 2020 legislative session, a bill was gaining traction that would have required teachers to receive at least one unit of professional development for social emotional learning.

The bill, pushed by the Mississippi Association of Educators, died when the Legislature recessed as the pandemic was first hitting, but its proponents intend to file it again next session.

MAE has also coordinated Zoom meetings for educators that provided tools for them to bring back into the classroom when dealing with social emotional learning.

In addition to that, Jones, president of MAE, is advocating that schools spend the first 30 days of class focusing mostly on social emotional learning. What might that look like?

“Just having a conversation with the student so the student is able to put their feelings into the room so the educator can gather that. Also not doing a deep dive into academics because the students are already stressed out,” Jones said.

At the Mississippi Department of Education, officials are also working on creating standards for social emotional learning.

In July, Dr. Nathan Oakley, chief academic officer at MDE, told the State Board of Education last month that though it’s just in draft form right now, it is “Work that we think is very timely right now for us as a state … When we look at a return to school, we’re not only concerned by the academic outcomes of our students and their progress in our content areas, but also have concerns about their social and emotional well being.”

Oakley added that the social emotional learning standards could be a useful way for teachers, guidance counselors and families help students build the skills that would help them as they develop academically and become students.

State Superintendent Carey Wright also said she had met with the Mississippi State Medical Association and the Mississippi Association of Pediatricians about the idea of telehealth and teletherapy that’s in the state’s plan for returning to school.

“They are very excited about the whole idea of telehealth and teletherapy that’s in our plan. They want to partner with us and they are willing to do whatever it is that we need to do to ensure that the children of our state get the health care that they need and the therapy that they need,” Wright said.

Until these efforts get worked out, teachers are still on their own when it comes to figuring out how to skillfully handle their students’ mental health.

“These students have experienced trauma,” Turner, the chemistry teacher, said. “It may not seem like it to some people, but there is trauma there and those needs are going to have to be addressed. The training that MAE provided, it did help, but of course we need prolonged training. We need ongoing training to help us understand how to support our students in this situation.”

The post How teachers are dealing with student trauma appeared first on Mississippi Today.

Read more about it

Read more about it