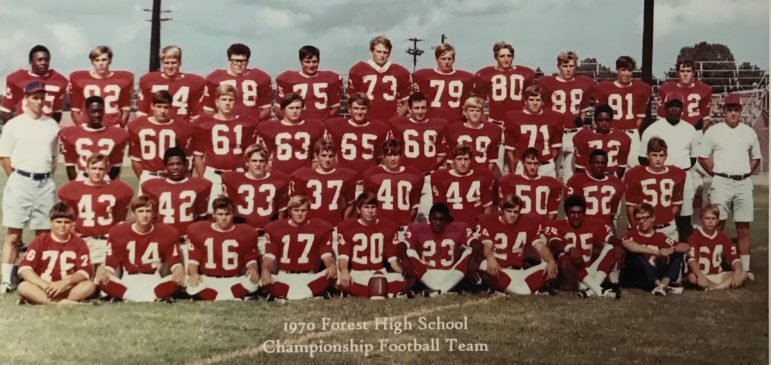

The 1970 Forest Bearcats: ‘We weren’t thinking about making history…we were thinking about making touchdowns’

By Rick Cleveland | Aug. 27, 2020

FOREST – Fifty years ago this month, the young people of this Scott County town had no idea what to expect. They just knew life – and school – would be different because the two high schools in town were combining into one.

Previously all-white Forest High School was merging with previously all-black E.T. Hawkins High School. There would be no black school, no white school – just one school. This was happening all over Mississippi. And, as happened in many communities across the Magnolia State, the football team showed the way.

Before we proceed, you should know this: Football was – and still is half a century later – huge in Forest. The Forest High Bearcats were a Little Dixie Conference power. The E.T. Hawkins Black Bearcats had a proud history as well.

Football practice started a month before classes began. In Forest, the first black and white students to mingle were the football players. You should know the 1970 season would have been a season of change even without integration. Gary Risher, a 28-year-old Forest native, was taking over for his former boss, Ken Bramlett, who had moved on to a college job after leading the 1969 Bearcats to a 10-0-1 record and the Little Dixie championship.

But graduation losses had decimated that team. Eighteen seniors had been lost, including several who would go on to play college ball. Risher, a former Bearcat himself, wasn’t starting from scratch, but he was definitely rebuilding and time was short. Risher hired another former Bearcat, Billy Ray Dill for one of his two assistant coaches. Those two led Forest through spring workouts, not knowing if integration would occur the next school year or be delayed until 1971-72. Risher kept the other assistant’s job open.

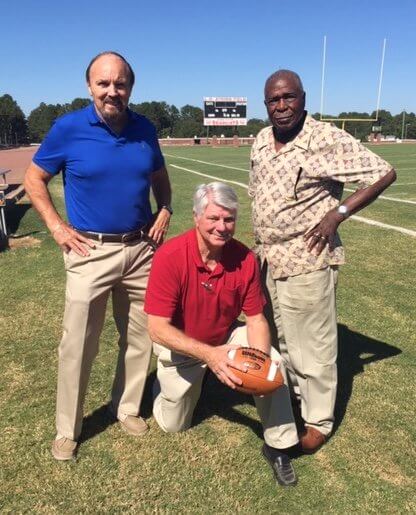

Once the decision was made to fully integrate for the 1970-71 school year, Risher made one of the best coaching moves he would ever make. For his line coach, he hired James “Bo” Clark, another Forest native, who had been the head coach at Hawkins. Amazingly, it seems now, Risher and Clark had grown up in the same town, been high school coaches in that same small town and had never met.

The same was true for the players. Said Lee Dukes, a senior wide receiver/defensive back who had never had a black teammate or classmate: “We lived in the same town, we walked the same streets, but we didn’t know one another.”

In 2016, Clark talked about the day he was hired by Risher. “I was working T-ball games, my summer job,” he said. “I looked up from what I was doing and saw a man get out of a pickup truck. He walked toward me and asked if I was Coach Clark. I replied I was, and then he introduced himself as the new Forest High football coach. He asked me to be his line coach and stressed the point he would not tell me how to coach the linemen. That would be my responsibility; he just wanted results. We shook hands on it, and he said, ‘Let’s go to work.’ Believe me, we did.”

It was brutally hot that August and the team practiced twice a day. It is said that misery loves company and perhaps that helped the black and white players come together. They shared the same misery. Said Willie Bowie, a wide receiver and kick returner who came over from Hawkins, “I am not going to lie. Those two-a-days were tough, really tough.”

Eighty-five players showed up for the first practice. By the time the season started, that number was down to 40. The oddest part: Bo Clark, the black assistant coach in charge of the linemen, had no black linemen. All his players were white.

Forty-six years later, Clark remembered his first meeting with his players. “Gentlemen, I am going to be your line coach, and I am going to respect you as a player, and in due time I think you will learn to respect me as a coach. But one thing I know for sure, I am going to be your daddy away from home.”

Clark saw bewildered looks on all the white faces, so he repeated himself: “Gentlemen, I am going to be your daddy away from home. And when I blow this whistle, I better be the last man to hit the sled!”

As it happened, Clark did become much like a second daddy. “He was always there for you,” said Bubby Johnston, a lineman and kicker on the team. “You could talk to him, and he would always shoot straight with you. He was a great motivator.”

Risher, the young first-time head coach, was demanding, but he also tried to make football fun for the players. For instance, each week he would install a new trick play to be used in that week’s game.

Said Johnston, “We players ate that up. Some of those plays even worked.”

All three Forest coaches consistently delivered the same message, that the color of one’s skin made no difference, that they were all in it together with one goal: Win. And, boy, did the first integrated team in Forest history do that…

Said Bowie, then a junior and the fastest man on the team: “As teammates, we just treated one another with respect. We took care of business. We weren’t thinking about making history. We were thinking about making touchdowns.”

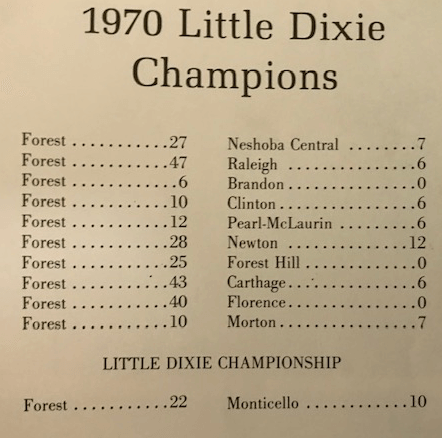

They made plenty of those, and they didn’t give up many. Only one opponent scored more than one touchdown. The Bearcats allowed fewer than six points per game, while scoring nearly 27 per game themselves.

The Bearcats opened with a 27-7 victory over Neshoba Central and followed that with a 47-6 trouncing of Raleigh.

Said Johnston, “You could feel the whole community coming together behind the team.”

Indeed, as Little Dixie Conference play approached, the community and the newly integrated school rallied around the Bearcats. This was back before Mississippi had any state playoffs and before high football teams were divided into classifications. Most of the state’s bigger high schools played in the Big Eight Conference. The Little Dixie was the next level. Competition was fierce with football towns such as Mendenhall, Magee, Brandon, Pearl, Clinton, Morton and Monticello among those in the mix.

Many of those conference games were defensive struggles decided in the fourth quarter. Brandon went down 6-0 on a late fourth quarter touchdown. Clinton fell 10-6 in a driving rainstorm. Joe Buddy Madden (white) and Lee Evans (black) combined to bat away a late pass and preserve a hard-fought 12-6 victory over Pearl.

Those Bearcats of 1970 prided themselves on playing physical, hard-hitting defense. Risher, the head coach, often left the last words of pre-game and halftime talks to Bo Clark. Those words were always these: “All right, let’s go hit somebody!”

Jackson homebuilder and accomplished golfer David Lingle quarterbacked the Forest Hill team that fell 25-0 to Forest. Forest Hill, a good team, ran the wishbone, which meant Lingle was a marked man since he ran the option on nearly every play.

“I felt like a rag doll out there, they beat me up so bad,” Lingle said, chuckling.

Fifty years later, he can laugh. Not then. Forest junior defensive end Jackie Calhoun, who would later play at Mississippi State, hit Lingle so many times he must have made himself sore.

Said Lingle, “If I handed off, I got hit. If I kept the ball, I got hit. If I pitched it, I got hit. Man, they hit hard. I remember walking off the field and their head coach coming up to me and saying, ‘Good game.’ I said, ‘It might have been a good game for you, but it wasn’t for me. I feel like I might die.’”

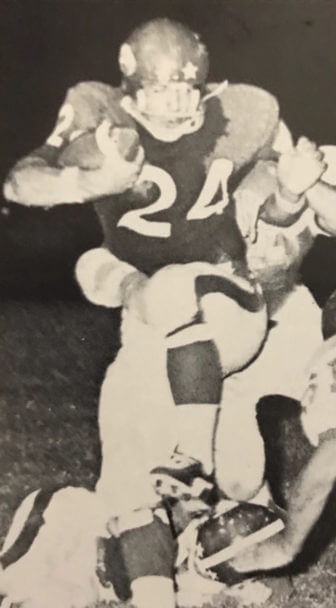

The Bearcats kept winning, even when Dukes, a star receiver and defensive back, went down with a leg injury. That just gave Bowie more chances to catch the ball and dazzle in the open field.

Risher called one of those trick plays in the Newton game. Quarterback Mike Massey passed to Bowie, who deflected the ball to fast-charging Ken Gordon, who raced to the Newton 7 to set up a touchdown in a 28-12 Forest victory. Most coaches would call that play a “hook and lateral.” Risher called in: “Sweet Georgia Brown.” His players loved it.

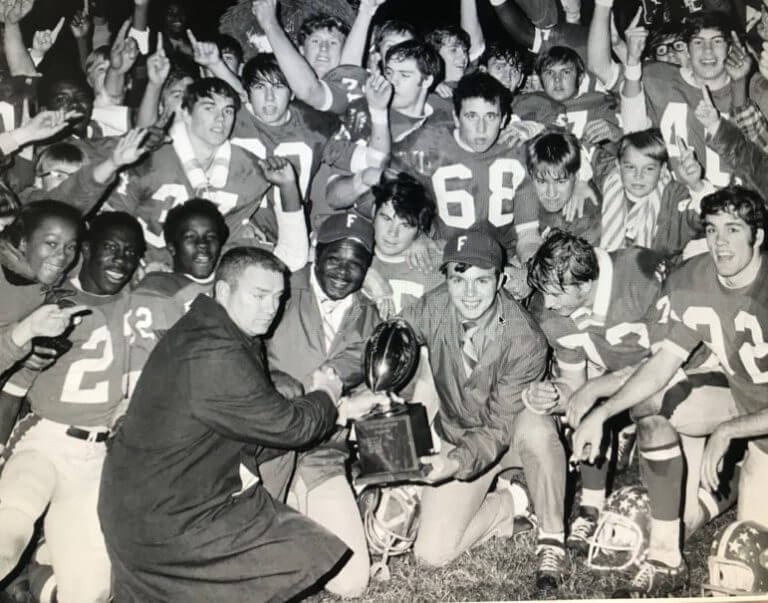

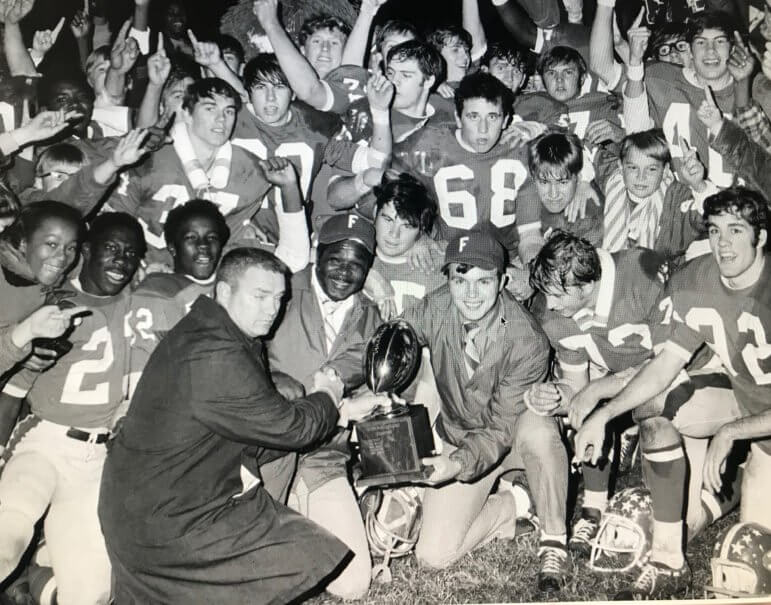

The Bearcats took a 9-0 record into the regular season finale against arch-rival Morton with the Golden Chicken trophy and the North Little Dixie Division title on the line. Despite the terrific running of Forest’s all-conference halfback Billy Thompson, Morton led 7-3 into the fourth quarter. Fittingly, the Bearcat defense delivered the winning points. Bobby Latham broke through the line to block a punt and Madden picked it up and ran it in for the winning points.

On the sidelines, Risher saw Lee Evans, a black defensive back, celebrating the go-ahead touchdown, dancing with Forest Mayor Fred Gaddis. Said Risher, “Ol’ Lee Evans was having a good time, dancing all around. I jacked him up and told him to get out there and he better make the next tackle. Well, he did better than that. He made several tackles in a row to clinch the victory.”

Forest, 10-0 and champion of the north, would play Monticello, winners of the South Little Dixie and coached by the legendary Parker Dykes, for the overall league championship. Risher, looking for an edge, switched from the Bearcats’ normal Power-I formation to a Winged-T to for the championship game.

That Friday was one Risher will never forget. Robin Risher, his infant son, became ill that morning and was rushed to a Jackson hospital where he was pronounced in critical condition.

“I got to the hospital and everyone was shaking their heads like there was no hope,” Risher said. “I was told to prepare for the worst.”

The Risher family was quarantined as a precautionary measure. Risher remained at the hospital while the Bearcats took on Monticello. “I had all the confidence in the world in Bo Clark and Billy Ray Dill,” Risher said. “There was no panic from anyone.”

There need not have been, although the score was tied at 10 going into the fourth quarter. That’s when Bearcats, as had been their habit all season, took over. Thompson, who rushed for 115 yards, scored two fourth quarter touchdowns to clinch a 22-10 victory.

Meanwhile, Robin Risher was diagnosed with meningitis. He would remain hospitalized for 10 days and would fully recover.

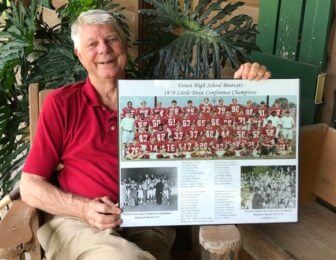

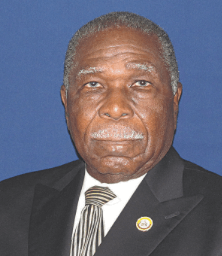

Fifty years later, the surviving 1970 Forest Bearcats are well into their 60s. At least seven have died, including Billy Thompson, the hard-charging 1,000-yard rusher and the team’s leading scorer with 67 points. Gone, too, is the much-beloved Bo Clark, who would serve on the Forest Board of Aldermen for the last 37 years of his life. Clark died last June. He was 88.

Risher, the head coach, is battling cancer. Dill retired after a career with the Chevron Oil Refinery in Pascagoula, where he last coached as offensive coordinator of an undefeated 1976 State Champion Pascagoula High team.

Surviving players and coaches will be celebrated at halftime of a Sept. 18 Forest-Florence game at L.O. Atkins Field, where 50 years ago the town’s first integrated football team, under a brand-new coaching staff, overcame so many obstacles to achieved perfection. In so doing, the 1970 Forest Bearcats helped bring two races, two schools and one proud town together.

The post The 1970 Forest Bearcats: ‘We weren’t thinking about making history…we were thinking about making touchdowns’ appeared first on Mississippi Today.

- Senate negotiators a no-show for second meeting with House on Medicaid expansion - April 25, 2024

- MDOC promotes inmate boxing program, but lawmakers say money could be better spent - April 25, 2024

- Medicaid expansion debate stirs memories of family medical debt for Mississippi senator - April 25, 2024