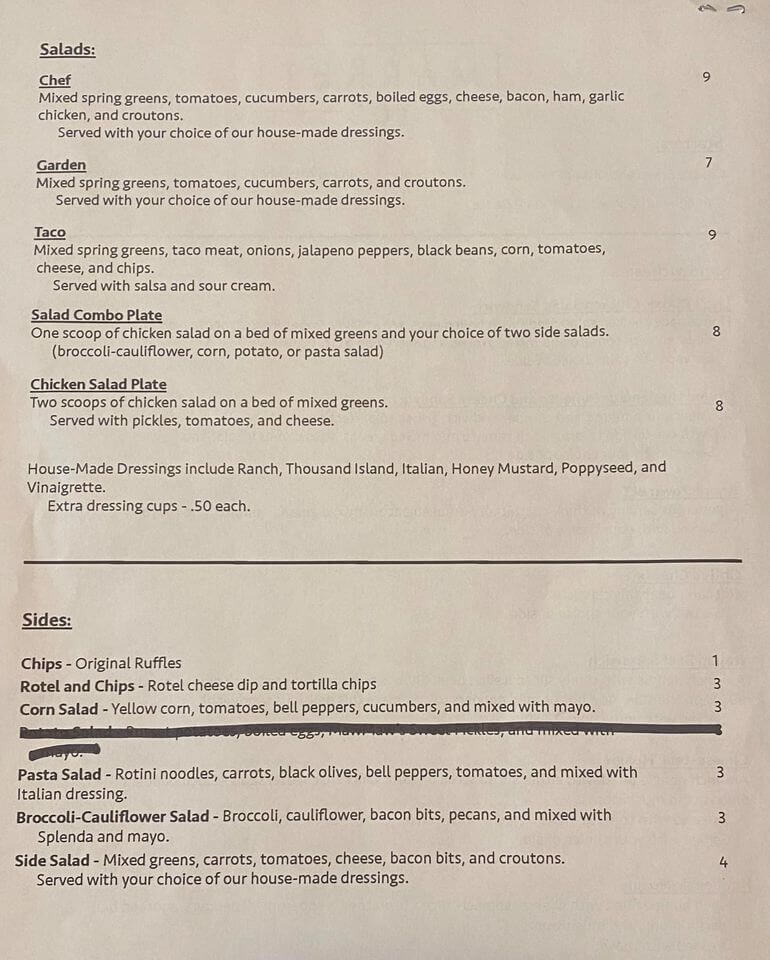

Eric J. Shelton/Mississippi Today

Commissioners selected this design called the “Great River Flag” as one of two finalists to become the new state flag.

After seeing five finalist designs flying over the Old Capitol on Tuesday, the flag commission on Sept. 2 will pick one of two designs to put before voters as a new Mississippi state flag.

“I think I’m going to love whichever one they pick,” said Lt. Gov. Delbert Hosemann, who was among a small crowd outside the Old Capitol watching the five finalists hoisted up a flag pole one after the other.

Voters in November will get a chance to accept or reject either a flag with a red-white-and-blue striped shield — inspired by the state’s territorial seal of 1798 — or a magnolia blossom, the official state bloom, on a blue background with red and gold stripes. Both, as required by a new law, have the words “In God We Trust” on them.

Both also include a large, main star with a diamond in it, representing the state’s Native Americans, and 20 smaller stars, representing Mississippi becoming the 20th state in 1817.

Eric J. Shelton/Mississippi Today

The second finalist chosen on Tuesday to become the new state flag.

The commission has winnowed the choices to these two out of thousands of submitted designs.

The Mississippi Legislature, after decades of debate, voted in June to remove the 1894 state flag with its divisive Confederate battle emblem. The legislation it passed created the commission to choose a new flag to put before voters on the Nov. 3 ballot. Voters can either approve or reject the new design. If they reject it, the commission will go back to the drawing board, and present another design to voters next year.

Hosemann on Tuesday declined to say if he had a favorite among the finalists or to handicap whether voters would ratify the final picked by the nine-member commission appointed by Hosemann, the governor and House speaker.

“It’s like (other elections), the primaries will soon be over and voters will have a design to look at and discuss the underlying meaning and symbolism,” Hosemann said. “It will be with a presidential election, so we’ll have good turnout. It will be the people’s flag, and if they don’t vote for this one, then we’ll do another.”

Felder Rushing, a noted horticulturist, radio show host and writer, was among the crowd watching the five finalists fly Tuesday.

“They look better in person than on paper,” Rushing said, a sentiment held by many attendees and commissioners on Tuesday. Rushing added that he is pulling for a design with a magnolia bloom.

The commission will take public input and online polling on the two remaining designs before picking a final one on Sept. 2.

The commission has had an attorney working with finalists to make sure there are no copyright or intellectual property issues — one of the finalists weeded out Tuesday included clip-art that would have posed a problem. And the commission instructed an attorney general’s office lawyer to do a background and social media check on designers. The lawyer said he had already done a preliminary check and none had criminal backgrounds.

“We don’t want to end up being embarrassed by someone whose background is not appropriate to what we are doing,” said commission Chairman Reuben Anderson.

One group, angered that the Legislature removed the old flag without letting voters decide, has started a petition drive to resurrect by referendum the 126-year-old state flag that featured the Confederate battle emblem prominently in its design.

The post Commission selects final two designs to become new state flag appeared first on Mississippi Today.